August is nearly here – the time when the contemporary art world in London begins its annual snooze, to wake up, hopefully refreshed, some time in mid-September. It’s the moment to draw breath, sit down and take stock.

It’s hard to think of any comparable six months when events have been more tumultuous.

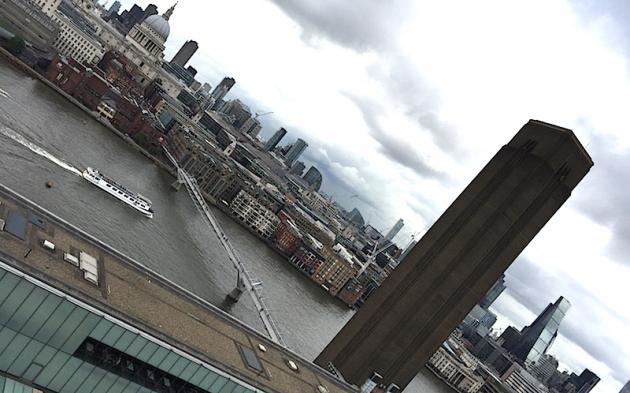

In the art world itself, there was the triumphant opening of the new wing of Tate Modern, which has already attracted more than a million visitors.

In the political world there was the vote for Brexit, which brought us a whole new government team: a formidable lady who voted Remain, at the head of a team of ministers populated with enthusiastic Brexiteers.

The two events seem inherently contradictory. Tate Modern now clearly sees itself as the epicentre of the booming global contemporary art world, which is very dependent on free trade and the free movement of goods. Little Britain attitudes are the last thing it wants to embrace, or can afford to embrace.

In fact a major difficulty for Tate, in its new guise, is going to be that of finding a convincing role for its elder, but now smaller, sister Tate Britain. Penelope Curtis, director for the past five years, and now departed to the Gulbenkian Museum in Lisbon, wasn’t particularly successful in doing this. It remains to be seen if her successor can do any better. One of his problems is going to be that big name British artists, alive and working today, will, given the choice, fairly obviously prefer to be shown at Tate Modern, with its huge audience and in the context provided by their international peers. The art-of-right-now is increasingly the name of the game, and Tate Modern is guaranteed to give it to you.

If Tate Britain is associated chiefly with the past, it will inevitably always be struggling. In fact it may even become emblematic of all the retrograde impulses associated with Brexit. It’s already noticeable, for example, that the ten most expensive American artists, as listed on the web, are all of them more or less contemporary. This is not true of the ten most expensive British artists. A slightly out-of-date list offers just Lucian Freud (born in Berlin), Henry Moore, Peter Doig (born in Scotland, raised in Canada, now resident in Trinidad), and Damien Hirst. Francis Bacon is mysteriously omitted, perhaps on the grounds that he was in fact Irish. The remaining six are Turner, Constable, Stubbs, Burne-Jones, Joshua Reynolds and Alma-Tadema (born in Dronrijp, the Netherlands, and trained at the Royal Academy of Antwerp).

Tate faces other problems as well. First, like other grandee institutions of the same sort, it is instinctively top down. It reserves the right to instruct its audience concerning the exact identity of ‘the-art-of-right-now’, and doesn’t take particularly kindly to being contradicted on this subject. It is, however, hard for it to maintain this stance – that of being in sole possession of superior, specialist wisdom – when faced with the immense proliferation of both information and opinions on the Web. Contradiction is at every user’s fingertips. More: the whole history of art, from the days of the French Revolution onwards, indicates that innovation in art has tended to be rooted in a whole series of multiple rebellions against and rejections of official authority. One thing Tate can’t escape is that it is in every sense of the term ‘official’.

The problem is compounded by other factors. One of them is simply generational. A lot of communication on the web is lateral – people of roughly the same age and interests communicating directly peer to peer, without the need for intermediaries. In these circumstances, dear old Auntie Tate, gathering up her skirts and attempting to get down with the kids, doesn’t cut a particularly convincing figure. Institutional populism, which is the direction Tate is now taking, is inevitably a bit condescending, and therefore, equally inevitably, a trifle suspect. I’m not pretending that I know the solution to this problem. I am only pointing out that it exists.

Things are further complicated by the crazy economics of the contemporary art world, one of the least regulated markets that exists. Auctions of contemporary art works play an increasing major role. So do teeming art fairs in various locations – Basel, Miami, London, New York, Istanbul. Artworks are instruments of value, but not necessarily valued for their own sake. Flipping art for profit has become a profession in its own right. If one looks at the patterns offered by all this, one perceives, I think, certain things, though once again without being able to offer solutions.

One factor is that there is nothing that can be reliably described as an avant-garde, in the old first-half-of-the-20th-century sense of that over-used term. Instead there is a proliferation of what can only describe as ‘novelty art’ or even as ‘gimmick art’. The 20th century avant-garde was about seeing things anew. What calls itself avant-garde now is increasingly often linked to the fashion for ‘appropriation’. Paradox is king. What appropriation proposes is that something is radical and new because what you are being asked to look at is obviously and defiantly not in the least new.

The supposedly avant-garde art of the present also tends to follow early to mid-19th century practice by taking up politics in a big way. Its ancestry includes Courbet and David, and more or less omits all new ways of actually looking at the world – all innovative processes of sight. Sometimes, as in the fading fashion for Conceptual Art, it proposes that you needn’t actually look at all. Reading and thinking are sufficient.

At the same time, however, there is accumulating evidence that the influence of political art, in terms of actual impact on events in the real world, is nil. It may make a big noise at the Venice Biennale, but it makes that noise in a bubble. Real politics take place elsewhere.

Where museums such as Tate are concerned, there is one final element of complication. The crazy current market in contemporary art is pricing even major institutions out. They are caught in a proverbial cleft stick. They can’t, being official bureaucracies, speculate by buying new talent when it is still cheap. They have to wait till the market gives them the OK. By which time what they might covet is usually out of their price range.

The instinctive reaction has been to look at kinds of art where he financial implications are not too drastic, but where the activity itself can still be presented an innovative. Hence, the rush towards performance art, video (technologically out of date almost as it is made, never fully in step with the latest commercial forms), and – yes – the kind of installation art that won’t survive more than a single showing.

Museums were invented to preserve the past. Now they rush to embrace the ephemeral. Tate Modern may be full of dead butterflies soon enough. If so, it won’t be the first time Tate has gone there. Remember the Damien Hirst retrospective of 2012? Dead butterflies were not in short supply on that occasion, but the institution was careful to omit any of the paintings Hirst actually made himself. When some these were shown three years earlier at the Wallace Collection, the reviewers trashed them. No wonder Tate ran away. I still wonder, however, if those in charge are now running in the right direction.

Words: Edward Lucie-Smith Photo: P C Robinson © artlyst 2016