It’s been quite a year for statues. Normally no more than street furniture that no one bothers to look at – old white men standing on plinths in all weathers extolling some arcane ‘victory’ of the Empire – statues have, recently, taken centre stage. First Edward Colston was toppled and thrown into the Bristol docks. Now Maggie Hambling’s homage to Mary Wollstonecraft is creating a furore on north London’s Newington Green.

A lumpen statue that is neither thought-provoking nor well-executed – SH

Yesterday her breasts and pudenda were covered with gaffer tape by outraged feminists. Over 90% of London’s memorials celebrate men, so this addition is significant. The Wollstonecraft Society’s stated aims were: ‘to promote the recognition of Mary Wollstonecraft’s contribution to equality, diversity and human rights and promote equality and diversity in education and stimulate aspiration and thoughtful reflection’.

Public sculpture is always a problem. It has to do many things for many people and is generally art commissioned and approved of by committee, rather than the free expression of a single artist’s imagination. In this case, Jude Kelly, the one-time director of the South Bank, and Shami Chakrabati are patrons, among many other well-known supporters from the arts. Unfortunately, there seem to be several briefs going on at once and none of them is really being fulfilled. On a recent Newsnight, Emma Barnett – no art critic – seemed to get a schoolgirl thrill from repeatedly talking about ‘tits’ on prime time TV while, at no point, discussing the work within a serious context of other contemporary artworks or even art history.

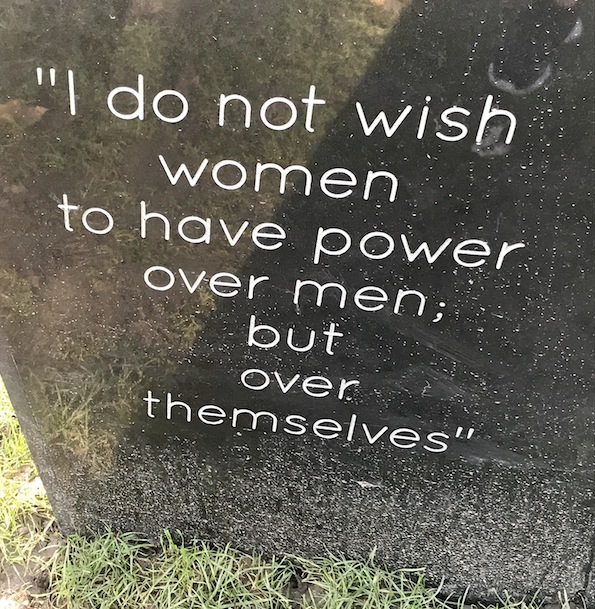

Mary Wollstonecraft was born into a family of straitened means. Her violent father made her acutely aware of the vulnerability of women. She would receive only a scanty education when formal education for women was not considered a right, yet would go on to write extensively about education for girls, establishing a boarding school on Newington Green.

Her writing career consisted of translations, reviews and books for children, whilst her travel writing influenced a number of early Romantic writers. But it was A Vindication of the Rights of Women(1792) that was her most crucial work; the first significant feminist tract. During her life, she had two important relationships. The first with the American adventurer and spy Gilbert Imlay, with whom she had a daughter during the French Revolution, and the anarchist and thinker, William Godwin, who fathered her second child who would become Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein and the wife of the poet. Mary Wollstonecraft counted among her friends the likes of Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Paine who came to Newington Green when in London to attend the Unitarian Church. She was, without doubt, a heavyweight in the feminist pantheon.

If nothing else, Maggie Hambling has succeeded in raising the visibility of Wollstonecraft among those who perhaps did not previously know of her existence. Speaking on Woman’s Hour today, she gave an articulate explanation of her work. But art is not a question of persuasive argument or language but of visual, emotional and intellectual impact. It has failed if it has to be justified in words. Language can only expand an artwork. In this case, the work needed to contain a sense of homage to its subject AND be a fresh and innovative artwork. It doesn’t really do either.

Today I went to Newington Green to see it for myself. It was a beautiful autumn day and I really wanted to like it ‘in the flesh’, so to speak, but it was worse than I expected. The problem is, not as many feminists seem to be objecting, that it incorporates nudity but that it is conceptually lazy, piling on cliché on well-worked cliché. A lumpen piece that is neither thought-provoking nor well-executed. If nudity is used, it needs to be the expressive language that carries the narrative weight of its subject. Think of the emotional charge of an edgy Klimt nude that no amount of linguistic explanation can replicate. It’s not the nudity that’s disrespectful to Wollstonecraft but that she’s been commemorated by the second rate.

From a distance, the oddly glitzy silver surface looks like one of those mascots that used to decorate the bonnets of posh cars or a chunk of amalgam recently extracted from a painful tooth. The sense of scale is off balance. The amorphous flow of ‘feminine energy’ leading to the tiny Barbie-doll figure standing on top like a sort of female Jack-in-a-box, crude. The simplified/idealised form with its gym abs and pert breasts carries no expressive resonance or historic charge. It’s not Everywoman, more Everyman’s wet dream. There is no sense of metaphor. No sense of history. Coming across it by chance it would offer up little of its point and purpose.

In his seminal text, Ways of Seeing, the late John Berger deconstructed the way that women were traditionally seen in art, suggesting that they were largely there to satisfy the male gaze. Revolutionary at the time, this insight meant that we could never go back to looking at a nude again without asking who it is for and what it is trying to say? That Maggie Hambling – who is really not a sculptor but a painter – should produce something so old fashioned and so ill-considered is a missed opportunity to put an iconic woman on the map. She might have chosen to make an abstract piece or a book on the lines of one of Anslem Kiefer’s great lead books or a realistic sculpture such as Gillian Wearing’s powerful commemoration of the Suffragette, Millicent Fawcett, in Parliament Square. Many have argued that the piece is being criticised simply because it’s new’ and that that is the fate of all ‘modern’ art. But that’s really not the case. It fails because it’s ill-executed because it doesn’t catch the spirit of Wollstonecraft and doesn’t employ the grammar and language of sculpture with originality, imagination or panache with the result that it looks rather more like something that’s just escaped from an up-market garden centre than a longed-for commemoration of a great historic heroine – and that’s a real pity.

Words/Photos Sue Hubbard © Artlyst 2020

Sue Hubbard is a freelance art critic, award-winning poet and novelist. Her latest novel Rainsongs is published by Duckworth.