On 21 September, a statement quietly appeared on the website of the National Gallery Washington. It announced the postponement, of the “Philip Guston Now” exhibition, set to open at Tate Modern, London, February 2021 and travel to three major US museums. Many in the art world have been dismayed by this decision, especially in light of the BLM (Black Lives Matter) movement. The controversy, it seems, involves several of Guston’s works depicting hooded Klansmen, a recurring theme portraying the enemy within.

Mark Godfrey, Curator of the London show at Tate Modern, has publically stated, “Cancelling or delaying the exhibition is probably motivated by the wish to be sensitive to the imagined reactions of particular viewers, and the fear of protest. However, it is actually extremely patronising to viewers, who are assumed not to be able to appreciate the nuance and politics of Guston’s works”, he wrote on Instagram.

Joint Statement From Host Museums:

We are postponing the “Philip Guston Now” exhibition until a time at which we think that the powerful message of social and racial justice that is at the centre of Philip Guston’s work can be more clearly interpreted.

We recognise that the world we live in is very different from the one in which we first began to collaborate on this project five years ago. The racial justice movement that started in the U.S. and radiated to countries around the world, in addition to challenges of a global health crisis, have led us to pause.

As museum directors, we have a responsibility to meet the very real urgencies of the moment. We feel it is necessary to reframe our programming and, in this case, step back, and bring in additional perspectives and voices to shape how we present Guston’s work to our public. That process will take time.

David Anfam/ Artlyst Interview

Paul Carter Robinson: From your perspective, who was Philip Guston?

David Anfam: Guston was always a remarkable mix of different artistic impulses. On the one hand, he had a deep admiration for the past and Renaissance art, especially Piero della Francesca. If there was any doubt on this topic, then Peter Benson Miller’s fine 2010 exhibition Philip Guston: Roma, which went from the Aranciera di Villa Borghese in Rome to Washington’s Phillips Collection, explored and established that area once and for all.

On the other hand, Guston had a strong contrarian side – what Dore Ashton (in my opinion among the best writers on the artist) called an impulse to disturb the status quo, a resistance to his time. His left-wing or very liberal views, like those of various other Abstract Expressionists from Pollock and Rothko to Reinhardt and David Smith, would alone have made Guston an outsider and maverick, particularly given the sort of dystopian and often reactionary sociopolitical century through which he lived, including the rise of fascism and its latter-day guises.

From a more general perspective, there’s a recurrent urge on Guston’s part to embrace contradictions – abstract and representational, image-making and iconoclasm, art as a site for ideal beauty versus edgy social engagement. It’s what academe-speak calls “conflicted”. I happen to think that’s not the right word. A better description would be Ashton’s notion of a “Yes, but…” syndrome. Human life itself is full of contradictions, so any existentialist worth their salt from Dostoyevsky and Kierkegaard to Sartre and Ingmar Bergman – I’m thinking names at random – necessarily seeks to keep this dialectic in play.

PCR: What is your response to the Museum statement?

DA: Shocking. Period. As shocking as the growing tendency of museums to deaccession. Sometimes diplomacy, discretion, restraint, even silence are the correct order of the day. Sometimes matters require real action, speaking out. This farrago has sparked my imperious streak, so for once I won’t hold back. Frankly, I think that in an ideal world the four curators should have tendered their resignations – as a matter of ethics – unless the respective museums agreed to revisit, with a view to hopefully rescinding, their decisions. Of course, nobody wants to be out of a job, especially in these evil times. I mean, it’s not as if we’re in an age of chivalry or gentlemanly noblesse oblige. Nowadays, people just say “sorry” for their mistakes or worse and carry on regardless. Welcome to politics. However, one reason why my reaction’s acute is because it’s that bad. With the volatile state of the art world, global economy and other challenges, museums are in greater peril than ever before. Hence an old adage is relevant: the best way to defend is to attack. Don’t back down. Be bold. Stick to your guns.

PCR: Looking at Guston, who was an outspoken left-wing liberal, Anti-War, Anti-Nixon and anti-KKK activist, do you think these images can be misinterpreted?

DA: Anything can be misinterpreted. Here I’m reminded of an otherwise maybe outlandish reference point—the literary critic and greatest Shakespeare scholar of his age, Sir Frank Kermode. Kermode has counted among my prime intellectual mentors in spirit ever since I first started thinking about art in depth as an undergraduate at the Courtauld in 1973. In a brilliant book on the origins of narrative in Biblical texts, The Genesis of Secrecy, Kermode argues that story-telling is intrinsically what they call polysemous – simply put, open to multiple interpretations. Nobody was more into story-telling than Guston. So, of course, his images can be misinterpreted. But this isn’t the point.

The point is the hideous trend of dumbing down and wrong-headed political correctness that has increasingly taken hold of people and institutions who should know and do, better. Like universities, museums ought to educate, enlighten, uplift and foster thought – not push mindsets further into silence, into crass know-nothingness. If topics are sensitive, then that’s all the more rationale for bringing them out into the open for debate. Otherwise, what’s the point of democracy, of a supposedly “open society”? We hear so much these days about museums striving to do community outreach and the like. How better to reach out to the community than to show art that frankly addresses such issues as racialism (I use the old-fashioned English word deliberately because that’s what my family called it in the 1960s), gender and diversity. By depicting the KKK, satirising Nixon, alluding to the Holocaust and many other strategies, Guston hit these kind of nails right on the head.

In fact, I regard Guston’s revolt against abstraction with the resurgence of a new, scandalous figuration at the end of the 1960s as, in a sense, a kind of unruly paean to diversity on the canvas ahead of its time. By then, Clement Greenberg’s critical doctrines about formal “purity” – in hindsight, I can’t help hearing an undertow to this word, a kind of aesthetic equivalent to ethnic cleansing – were threatening to become an art world dictatorship. With his pungent imagery, Guston was a rebel with a cause. He bore witness. If great museums such as the NGA, the two MFAs of Boston and Houston, even Bankside, cannot present Guston’s work in ways that enable people to learn what his real aims were, they may as well deaccession their Pieter Breughels, their Goyas, their Guernicas, Norman Lewises, Leon Golubs and Georg Grosz and shut their venerable doors today.

By now, this exchange has also jumpstarted the ruthlessly moral “Clyfford Still” angle to my personality! Not to mention my emotions because I am ultimately speaking as someone whose extended family tree includes Russian Jews, black Ghanaians, Irish Catholics, Welsh Protestants, devout Indians, straight-laced irreligious Cockneys, Cambridge graduates and more besides. My father was reading James Baldwin, Malcolm X and Norman Mailer’s “The White Negro” – among many other books – decades before anybody had heard of the “Black Lives Matter” slogan. I will believe endless museum talk about “diversity” and so forth when the majority of staff who clean them after hours are not Blacks or Latinos or other people of so-called BAME identity. The culture wars don’t just need to be fought; they need to be won by the right side. And let me be very clear: Guston was always on the right side. His LA was that of the WASP corruption, machinations and prejudice pictured in Polanski’s film Chinatown (1974) and Raymond Chandler’s novels. Mayhem was its other name. Watergate, Vietnam, Martin Luther King, the Kent State killings, the Chicago riots and other key figures or watchwords of the 1960s and ’70s were the precursors to today’s ubiquitous political and social troubles. The sheer ferocity of Guston’s late imagination – the fearlessness with which he tumbled barriers between “high” and “low” with paint that he once likened to coloured “dirt” – makes this the perfect moment to keep the artist in the spotlight. To be fair, the weighty catalogue to the postponed show, which I’m reading right now, goes some way in this very direction, particularly with its verdicts on Guston by ten contemporary artists. In Guston’s devastated or infested land-cum-mindscapes as well as his deluges – sparked, if anything, by the shock of Hiroshima and the death camps – I also seem to discern prophetic hints, as pungent as they are fortuitous, of our present-day state of eco-angst about climate change, toxic chemicals and other manifold woes that humankind has brought on itself.

PCR: Why do you think the Guston show was pulled?

DA: Given a choice, human beings tend to prefer a quiet life. Nor am I talking from an ad hominem standpoint. On the contrary, I spent almost ten good years at the NGA and my catalogue raisonné of Mark Rothko’s paintings could never have happened without it. Likewise, I’ve long had the greatest admiration for Gary Tinterow, a masterful museum director. The bottom line is that curators report to directors and directors report to their Boards, which are understandably risk-averse. Nobody likes a big stink and it’s to Guston’s credit that he was a perennial rabble-rouser in the very best sense of the word. To the legally minded, there’s also the worry of litigation for some reason or other waiting in the wings. Better to play safe with Annie Albers’s textiles and what I call “Gold of the Gorgonzolas” type of shows with mouth-watering treasures, dizzying historical vistas, and so on.

PCR: What is the role of Curator these days?

DA: Everything from self-styled greenhorn curators who wouldn’t know a Rembrandt from an ironing board, via those whose idea of heaven is to do a muddled Biennale or Art Fair event anywhere and everywhere, to true thinkers who place their own distinctive stamp on how to organise, celebrate and show art in its sharpest light even if the message ruffles proverbial feathers. If memory serves, I was taken to task more than once regarding my Royal Academy show by members of the public asking why this or that name – that had nothing to do with Abstract Expressionism even broadly defined – wasn’t in the selection. Ho hum…

PCR: From your viewpoint as a curator of international touring exhibitions, what are the logistics, process and politics of mounting a touring show in several countries today?

DA: It’s getting tougher by the day. Apart from the usual museum politics that are as old as the hills, Covid-19 has thrown everything on its head. Then there is the economics. The Royal Academy would have had to shoulder unimaginable expenses for Abstract Expressionism if it didn’t have a government indemnity. Likewise, the days when, say, the Mona Lisa could travel to D.C. are long past. With modern art prices soaring into the stratosphere at auction and masterpieces going into secluded private collections, securing loans can be a huge struggle. Being independent doesn’t make things any easier since museum curators naturally like to, well, curate themselves. Travelling a show complicates matters further. Unforeseen national/domestic problems can arise whenever an exhibit travels to another country. For example, could anything remotely risqué be toured to certain countries in South America, a continent that I love? A different museum may have a completely changed concept of the show from its original venue. When I did a focus selection around Jackson Pollock’s epochal Mural for the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice in 2015, it was fascinating to witness how transformed the installation became in Berlin and Málaga’s Museo Picasso.

PCR: Do you think the climate has shifted to the point that museums are afraid of offending and in this example have pulled the show rather than explain the work to the public with plaques and statements?

DA: Yes. Again, it’s a symptom of a far greater malaise already mentioned, dumbing down. Personally, I’m disappointed if I don’t encounter a word that sends me to the dictionary once a week. It’s the opposite in many museums now. Writing wall-texts in the U.S. can be a wordsmith’s nightmare. Speaking of which and before I forget, doing the wall texts for the Guston retrospective when it toured to the R.A. in 2004 was tremendously enjoyable:

My maxim? Never a single excess word. Some exhibitions have left me feeling at the end of the day that I don’t really like the artist. But that’s no bad thing. At least they made me think. With its legacy of a military junta in Greece and the concomitant sway of ultra-conservatism, I worried that maybe my Lynda Benglis show in Athens might stir up trouble: Lynda’s made some very daring visual statements about gender. Not so. If anything, I actually think there was quite a bit of welcome discussion about issues relating to women and their rights.

PCR: Do you think the National Gallery of Washington as a publicly funded institution has played a key role in the cancellation of the show and do you think that the cancellation of the show was a political decision?

DA: Truth to tell, I don’t know and would prefer to avoid the blame game anyway. I do know that I was originally approached by the NGA to write for the catalogue. But time and tide finally got the upper hand, I guess. If I am correct, the NGA reports to Congress, which could be a definite consideration to bear in mind. Insofar as the personal is the political, all such decisions belong to some degree to the latter sphere too. Am I sounding like a Sixties leftover? #1

PCR: How much power and influence do corporate sponsors have?

DA: A lot. Money makes the world go round. What gets tough is knowing when to draw the line between much-needed sponsorship and lucre that comes with strings attached. In that event, the tail wags the dog.

As it happens, in The Line from 1978, Guston painted precisely that linear gesture, evidently ascribing it to God. Man proposes God disposes. As with various Abstract Expressionists, I take Guston as perhaps something of a god-seeker in a fallen world. The rampant shoe soles, for instance, have a precedent in Hogarth’s Rake’s Progress. In one print Hogarth makes a visual pun on “sole” and “soul”. In short, corporate sponsors are a Faustian pact that needs to be treated with great deliberation re the pros and cons.

PCR: Who do you think is ultimately responsible for the cancellation of the “Philip Guston Now” show?

DA: Now you’re trying to draw me. Watch out I don’t pull the Fifth Amendment or something.

PCR: Frances Morris, Director of Tate Modern’s silence has been deafening. Do you think Tate should have made a public statement and taken a stand?

DA: Again, yes in thunder. Silence = death.

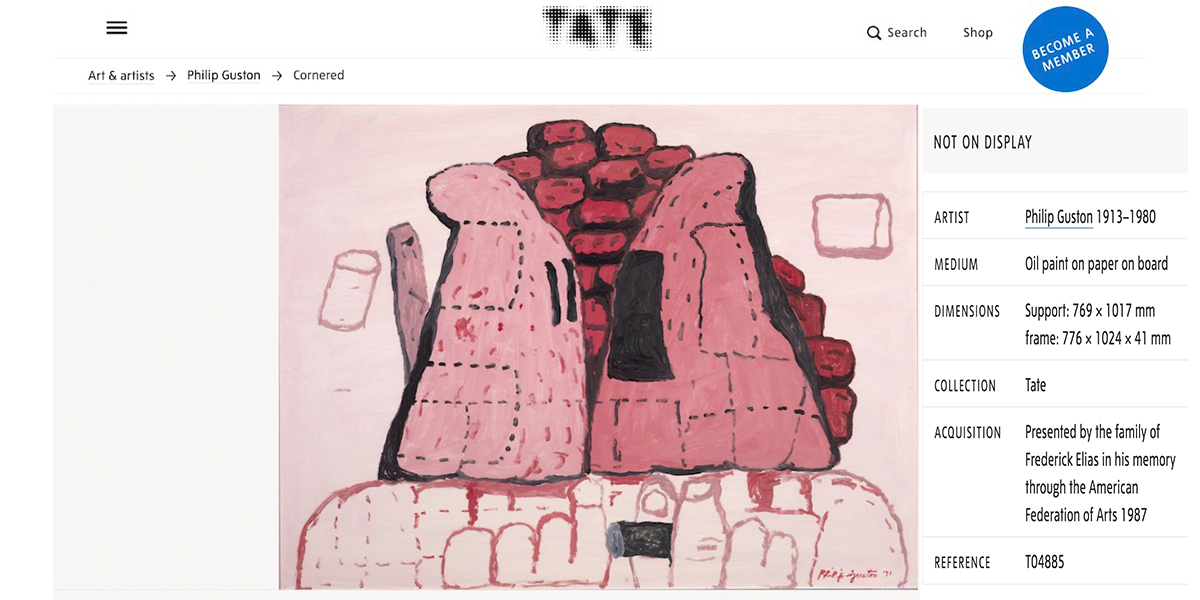

PCR: The Tate permanent collection includes one of Guston’s Klan paintings. It is not currently on display but appears on the website with a thorough explanation. Should it now be displayed in lieu of the show?

DA: The Tate actually has three excellent Gustons. Their website indicates that none of them are on display at the moment. Why? Recall, too, that Tate Liverpool had a Guston show in 2002 and another took place in Edinburgh’s Inverleith House in 2012 not to mention the R.A.’s big retrospective. I walked round it with Sir Norman towards the end of the installation. A superb show that didn’t, one suspects, do terribly well at the box office. So maybe London was not a great choice for the present tour. While we’re talking, the Tate also has one of my favourite paintings, Bernard Perlin’s Orthodox Boys from 1948. It’s on loan at the moment, while I don’t recall ever having seen it on Tate’s walls. Perlin deals with issues of Jewish identity in a hostile environment, a subject very central to Guston’s vision. It’s timely to note that the KKK and their sympathisers didn’t just lynch Blacks. A national cause celèbre was the lynching of the young Jew Leo Frank in 1915. As I’ve noted elsewhere, this appalling anti-Semitic mob violence could not possibly have escaped Guston’s notice. Similarly, my guess is that the almost trompe l’oeil swastika in his early mural in Morelia, Mexico – Fred & I made a pilgrimage to see it in 2011 – maybe perhaps the first Nazi swastika depicted in serious art outside of the German-speaking countries. At one level, Guston is a magnificent “trauma artist”. The twenty-first century is nothing if not filled with traumas both personal and collective.

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/guston-cornered-t04885

PCR: Philip Guston’s daughter, Musa Myer said, “I am deeply saddened by the decision of the museum directors not to exhibit the Philip Guston Now Exhibition”. Where does this leave the Guston Foundation in terms of organising future exhibitions?

DA: The decision to postpone the show might become a shot-in-the-foot. In other words, museums elsewhere may rise to the occasion and Do The Right Thing. Furthermore, Guston is fortunate to have a very major representative in the form of the uber-dealer, Hauser & Wirth. You can be sure that H&W will do their duty in terms of future exhibitions. Already in January this year Musa Mayer curated the show Resilience: Philip Guston in 1971 for their L.A. space and wrote the heartfelt catalogue essay:

https://www.hauserwirth.com/hauser-wirth-exhibitions/25268-resilience-philip-guston-1971

DA: These are all auspicious pointers to the future.

PCR: If the museum establishment boycotts Guston, will this affect the market for his work?

DA: Nope. In this capacity, dealers have increasingly replaced museums.

David Anfam has curated five major exhibitions at the Clyfford Still Museum, Denver. For the non-profit arts organisation NEON, Anfam also curated Lynda Benglis: In The Realm of the Senses at the Museum of Cycladic Art, Athens, which closed this March. His Abstract Expressionism at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, in 2016-17 was the largest survey of the subject ever held in Europe.

#Note – The National Gallery of Washington is a private-public partnership. The United States federal government provides funds, through annual appropriations, to support the museum’s operations and maintenance.