In 2020, I wrote an article: ‘The Trouble with Problematic Public Statues’, sparked by the felling of slave trader Edward Colston’s effigy in Bristol. Unsurprisingly, since then, the debate has remained inflamed. In this article, I seek to go beyond the continuing rhetoric to describe how the debate has evolved and to examine how masculinity and other still pressing themes within public statuary might be reimagined.

Last week, one question about historical public statuary received something of an answer, at least for now, as the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) published guidance that contested historical sculpture be approached with a “retain and explain” policy. Historian and broadcaster David Olusoga, speaking on BBC Radio 4, gave this idea short thrift, asking, “Why would you want a statue of a man who was a mass murderer or a slave trader?”. He wondered more profound questions about what statues are for, proposing they might merely be “validation and memorialisation”. He specifically and rightly prioritised the question, “Why do we want to say that these were great men when we know, in many cases, they were not?”

Retain and explain or move into museums?

Beyond all the big declarations, there has already been a broad and concerted focus on the legacies and representations of perpetrators of slavery. According to the Guardian, “70 tributes to enslavers and colonists, including 39 names on streets, buildings and schools, as well as 30 statues, plaques and memorials” were removed in the six months since Colston was felled. Colston has been rehoused at Bristol’s M Shed Museum, where visitors can see the statue behind the scenes. The conversation started by this move gives widespread endorsement, at least in Bristol, with four out of five of 14,000 respondents to a public survey agreeing with the rehousing. In April 2022, the local Cabinet approved a decision for a more permanent public display, distinctly contrasting the retain and explain guidance offered by Whitehall, posing the question, are statues that have already been removed to be put back?

A sculptor’s perspective:

To my mind, the role of a good artist is to make and present work authentic to their individual experience that meets and connects with an audience. Public art (as opposed to public sculpture), at its best, brings shared experiences together or proposes new ways of thinking for much bigger audiences. Public art can offer a humanising reflectivity outside a gallery or museum every day and for everyone.

The public sculpture debate remains difficult because we confuse too many arguments, including what historical sculpture was and what contemporary public art is and might be. The “might be” is critical, but there still appear to be gaps. That’s not to say there hasn’t been significant progress with some exemplary public commissioning, but it does feel patchy like tectonic plates still missing their connections.

If I delve a little deeper into my own experience and think of my first encounter with historical public statues, this began far beyond my formative upbringing in Devon, where there was little call for gargantuan bronzes. On trips to London, I would see these monumental sculptures, mainly of men, that I didn’t know or understand but thought must be critical. It’s only later that I can entertain the idea presented to me by my psychotherapist partner that these heroic figures might have been symbolic father figures for fatherless children, including myself.

I can now see that it’s not such a far-fetched idea. In truth, we each have our unique relationship with the archetypal sense of masculinity and, consequently, patriarchy, or beyond that, the heroic. Such depictions have classified and depicted masculine ideals, which are now questionable. The social elevation to the plinth has further solidified that proposition, underscoring notions of status and aspiration to further power. It’s no wonder whether of men precisely or now aged patriarchal ideals, many historical public statues look and feel troubling today. The supporting statistics are unsurprising; men and royalty are overrepresented, and women and ethnic groups are undervalued.

Everyone would agree that we need to tackle representations of mass murderers and slave traders head-on. Still, I don’t think anyone would propose abandoning broader terms of masculinity altogether. It’s the context and balance that needs to change. In the light of, or perhaps despite, government advice, we still need more creative, potentially-filled discussions with broader representation and certainly ones which avoid combative or stilled conclusions. Most importantly, we mustn’t fear looking directly at complex histories and thinking more broadly about new possibilities.

Conversations with history:

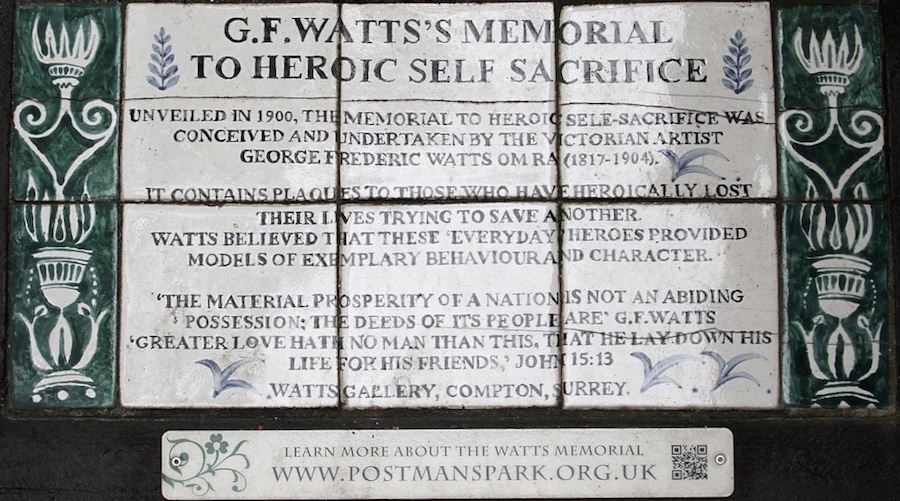

‘Postman’s Park’ in London is the 1900 location for George Frederic Watt’s ‘Memorial to Heroic-Self Sacrifice’, which remains an excellent and universal reflection on heroism beyond masculinity. It’s an inclusive memorial to ordinary people, men, women and children who died while saving the lives of others and who might otherwise be forgotten. It takes the form of a loggia wall housing ceramic memorial tablets. The work also inspired Susan Hiller’s breakthrough 1980-81 work ‘Monument’.

Speaking to the past whilst actively igniting a conversation about present and future connectivity is, to my mind, the golden thread of continuity and authenticity. Veronica Ryan OBE recently and eloquently dismantled the idea of the traditional plinth whilst going beyond gender, with the first British public installation to honour the Windrush Generation. It was presented in Hackney, London, not far from my studio. This is a celebratory monument rather than a memorial and is a masterclass in how to rethink. The work borrowed Caribbean-found fruit forms from nearby market stalls, representing them at a scale that abstracts from the literal, evoking an active, imagined relationship with the object. Classical materials add texture and colour, meaning the work evokes deep historical and personal narratives in visual and felt ways.

Only moments away, Thomas J Price pays equal homage to two 9ft bronze figures of a man and a woman based on digital 3D images of over 30 Hackney residents with a personal connection to Windrush. Such standout sculptures remain statuesque yet interrogate and actively inform what contemporary public statuary and art is and what it can be. Art can draw in histories and stories and mirror them to us regardless of race, gender or sexuality. They become sites to gather and reflect actively; they become calls to action to influence change.

Between the historical and the contemporary:

I was recently commissioned by the London art agency ARTIQ to create eight bespoke sculptures for the Old War Office, the site of the new Raffles London. Each sculpture comprises a brass horse, partly concealed by a coloured ceramic drape, set atop a classical marble plinth. Each sculpture occupies a corner suite facing Whitehall, which overlooks the Horse Guards Parade and historical statues lining the street, an ideal context for the interplay between historical and contemporary meanings. Each sculpture also sits alongside images of female heroines in wartime, from Vera Atkins and Odette Sansom to Clementine Churchill, adding another intriguing curatorial layer.

Reconfigured heraldic symbols, marble, brass, ceramic and paint. Photo: Richard Stone

The ceramic drape, for me, operates ambiguously between covering/uncovering/recovering and, in this way, might be seen as a magician’s cloak, implying that it’s thrown over something in the arrested moment between what it is – or was – and what it might be. Whilst I can only offer the sculptures themselves, I hope they might invite curiosity and provide a unique perspective on reimagining historical public statues as contemporary art.

All of us seeking a resolution to historical public statuary and more inclusive and representational public art, be it artist, commissioner, government or the public, must, I believe, reach deeply into themselves as we face these fast-evolving cultural and societal moments. In this way, we can all usefully connect with the wounds of history and modern-day failings to reach something more transcendent. This desire for learning and reimagining should be more critical and inspirational than what governments can do or say about public statues for what might be seen as their political purposes.

Top Photo: Defaced Colston Statue at the M Shed Museum, Bristol Courtesy Wikki Commons

Richard Stone is a contemporary artist. He served three years as a Trustee of The Royal Society of Sculptors. He is represented by Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery.