One of The Most Important Impressionist Paintings to Come to Auction in the Last Decade Will Be Offered in Sotheby’s February 2014 Impressionist & Modern Art Evening Sale. Camille Pissarro’s Boulevard Montmartre, matinée de printemps of 1897, originally owned by Max Silberberg, a Jewish industrialist based in Breslau, who assembled one of the finest pre-war collections of 19th and 20th Century art in Germany. Forced by the Nazis to sell his entire collection, he later died in the Holocaust. The painting was restituted in 2000 to Max Silberberg’s family and will now be offered at auction in Sotheby’s Impressionist & Modern Art Evening Sale on 5th February 2014 with an estimate of £7-10 million.

Helena Newman, Chairman of Sotheby’s Impressionist & Modern Art Department Europe, said: “It is an honour to be entrusted with offering the greatest work by Camille Pissarro ever to appear at auction – a work that encompasses such a richly painted canvas and a supremely elegant composition. The appeal of these extremely desirable attributes to discerning collectors is enhanced by the painting’s history of having been housed in a collection as important as Max Silberberg’s. With the enduring demand for Impressionist masterpieces – particularly works of such rarity as this work by Pissarro – we anticipate interest from around the globe.”

A prominent member of the business community in Breslau, and a generous patron of Jewish causes, Max Silberberg assembled an art collection that included magnificent examples of classic French Impressionism by Manet, Monet, Renoir and Sisley, as well as masterpieces of Realism and Post-Impressionism including several works by Delacroix and Courbet alongside paintings by Cézanne and van Gogh. He acquired works directly from prominent artists with whom he established strong friendships – including Max Liebermann – as well as from some of the greatest galleries and dealers, including Paul Rosenberg and Georges Bernheim. At the time he was ranked as a collector alongside Andrew Mellon, Jakob Goldschmidt and Mortimer Schiff, and his collection gained international renown. The collection was well published and works from it were in demand for exhibitions around the world, and as late as 1933 his paintings were generously loaned for shows in Vienna and New York.

By 1935 Max Silberberg was forced to relinquish his public roles, his company was Aryanised and sold and his house was acquired by the SS. The collector was compelled to consign most of his wonderful collection at a series of auctions at Paul Graupe’s auction house in Berlin in 1935 and 1936 (including Boulevard Montmartre). In 1938 his son Alfred was arrested on Kristallnacht and taken to the Buchenwald concentration camp. Alfred was permitted to return home a few days later on the condition that he depart the country immediately. Max Silberberg and his wife Johanna, however, were deported to Theresienstadt and then to Auschwitz in 1942. Their son had both his parents declared dead in 1945.

The opening of German archives in the 1990s shed light on the identity of individuals affected by the ‘Jewish auctions’ in which German Jews were forced to sell their possessions at below-value sums. Many heirs of Holocaust victims were suddenly able to seek the recovery of works of art and other valuables that were taken by the Nazis.

Alfred Silberberg had emigrated to England with his wife Gerta, and while he had passed away in March 1984, she survived him and took up the search for the artworks that had belonged to her father-in-law prior to the Nazi era. In 1999, Gerta became the first British relative of a Holocaust victim to recover a work of art under the Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-looted art.

An exquisite calligraphic drawing of an olive grove by Van Gogh, L’Olivette (Les Baux), Olive groves with Les Alpilles in the background had found its way from Max Silberberg’s collection into that of the National Gallery of Berlin – testament to its outstanding quality – where it remained until its history came to light, at which point the museum was instrumental in its prompt restitution, a landmark case in Germany. The work was sold at Sotheby’s in December 1999 for £5.3 million – then a record price for a pen and ink drawing by the artist. At the time, Mrs Silberberg said, “Obviously, I have no wish to receive the pictures myself. I wish to continue to live modestly and quietly for my remaining years”. Proceeds from the sale helped fund the search for further works of art that had belonged to her father-in-law, and the drawing was gifted by the buyer to the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Boulevard Montmartre, matinée de printemps, one of the most important works in Max Silberberg’s original collection, had also made its way into an important museum collection. Following its forced auction in Berlin in 1935, the work passed through a number of hands until its sale in 1960 to John and Frances L. Loeb. In 1985 the Loebs promised the painting to The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, in honour of its Founder Teddy Kollek and on the occasion of its 20th Anniversary, and bequeathed it to the American Friends of the Israel Museum in 1997. Following a four-month period of intensive research, undertaken jointly by the museum and by representatives of Gerta Silberberg in 1999, the work was restituted to Gerta Silberberg in 2000. In appreciation of the museum’s exemplary and groundbreaking efforts on her behalf, Mrs Silberberg loaned the painting back to the museum, where it remained on display for the remainder of her life. (Gerta Silberberg passed away earlier this year.)

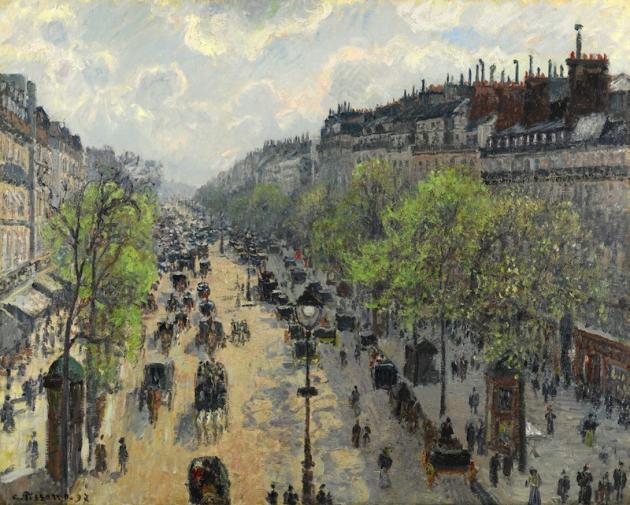

Camille Pissarro’s series paintings of Paris are among the supreme achievements of Impressionism, taking their place alongside Monet’s series of Rouen Cathedral and the later waterlilies. He worked methodically for over two months on his Boulevard Montmartre series and held this particular painting in especially high esteem, writing to his dealer Durand-Ruel, ‘I have just received an invitation from the Carnegie Institute for this year’s exhibition: I’ve decided to send them the painting Boulevard Montmartre, matinée de printemps… So please do not sell it’*.

Pissarro’s series of paintings of Paris executed in the last years of the 1890s were hugely significant achievements that brilliantly evoke the excitement and spectacle of the city at the fin-de-siècle. For an artist who throughout his earlier career was primarily celebrated as a painter of rural life rather than the urban environment, the Boulevard Montmartre series was among a small group that confirmed his position as the preeminent painter of the City.

The artist was able to exploit the artistic possibilities presented by the new urban landscape of Paris that Haussmann’s renovations to the city had created. He extolled the artistic possibilities in a letter to his son Lucien: ‘It may not be very aesthetic, but I’m delighted to be able to have a go at Paris streets, which are said to be ugly, but are [in fact] so silvery, so bright, so vibrant with life […] they’re so totally modern!’ ** Pissarro’s views of Paris focused principally on the new vistas, which not only proved highly successful artistically but also critically and commercially, since the extensive grid of straight roads, avenues and boulevards was the setting for a burgeoning middle-class, whose appetite for modern painting far outstripped that of the established aristocracy.