Robert Irwin, a prominent Southern California art scene figure and a key contributor to the 1960s Light and Space movement, passed away on Wednesday in the La Jolla section of San Diego. He was 95. Irwin, known for his transition from Abstract paintings to creating ephemeral and often intangible art environments, left an enduring legacy.

Irwin’s pioneering work in exploring the interplay of light, space, and architecture redefined artistic expression, making him one of the most influential figures in modern art.

His artistic journey began in the late 1950s when he embraced Abstract Expressionism. His early works, displayed in a monographic exhibition at the Felix Landau Gallery in Los Angeles in 1957, laid the foundation for his distinctive style. Transitioning to the Ferus Gallery in 1958, Irwin delved into more nuanced creations characterised by line and dot paintings. These artworks, driven by intricate questions of structure and perception, began his transformative artistic exploration.

In 1966, Irwin took a radical turn, creating curved aluminium and acrylic discs that defied traditional artistic norms. These groundbreaking works, displayed innovatively, challenged viewers’ perceptions, ushering in a new era of creative engagement. By 1970, Irwin abandoned the traditional studio setting, embarking on a journey of ephemeral interventions in existing spaces. His artworks blurred the lines between space and artwork, delving into the nuances of light, volume, and perceptual psychology.

Collaboration and Conflict:

In a pivotal moment in 1969, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art extended an invitation to Mr. Irwin to participate in its Art and Technology program, a groundbreaking initiative pairing artists with scientists. For this venture, Mr. Irwin enlisted the expertise of Dr. Edward Wortz from the Garrett Aerospace Corporation and James Turrell, a fellow luminary in the Light and Space movement. Together, they delved into sensory deprivation experiments at the University of California, Los Angeles, meticulously documenting their observations.

However, this collaboration was not without its complexities. Before realising any artwork, Turrell withdrew from the project, sparking a legendary rift between the two artists. This discord led to a decades-long silence between them, a period during which they made deliberate efforts in interviews to delineate their distinct artistic contributions.

Reflecting on their divergent approaches, Mr. Irwin remarked in a 2007 interview, “The difference between me and Turrell leaving a room empty is that Turrell would make you take your shoes off — it becomes a ritual for him.” This incident encapsulates the intricacies of artistic collaboration and the nuances that often define creative partnerships. The two artists did make-up years later.

Irwin’s impact extended far beyond traditional galleries. His permanent installations, such as “1° 2° 3° 4°” (1997) at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, La Jolla, and “Light and Space III” (2008) at the Indianapolis Museum of Art, redefined public spaces. His expertise also encompassed landscape design, notably demonstrated in his design of the Central Gardens at the J. Paul Getty Center in Los Angeles (1997), where he seamlessly merged landscape elements with architectural intricacies.

One of Irwin’s most ambitious projects, “Untitled (dawn to dusk),” graced the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas, in July 2016. Spanning 10,000 square feet, this installation transformed a former hospital building, orchestrating a symphony of light, space, and natural surroundings. This project, 15 years in the making, stood as a testament to Irwin’s unwavering dedication to his craft.

Irwin continued experimenting with various media in his later years, crafting sculptural works that transcended traditional boundaries. His art emphasized perception and context, challenging audiences to rethink the very essence of artistic experience.

His death, attributed to heart failure, occurred at Scripps Memorial Hospital in La Jolla, San Diego, according to Arne Glimcher, the founder and chairman of the international Pace Gallery, showcasing Irwin’s work since 1966. Irwin had been residing in San Diego at the time of his passing. He is survived by his wife, Adele (Feinstein) Irwin; their daughter, Anna Grace Irwin; and a sister, Patricia Keenan.

His gallery made the following statement:

Pace is deeply saddened to announce the passing of artist Robert Irwin on October 25 at age 95.

A monumental figure in the California Light and Space movement, Irwin made innovations across painting, sculpture, and installation-based work over nearly seven decades, expanding the contours of the canon and continually pushing the limits of what art can be. Through his influential and experimental practice—marked by scientific and philosophical rigour—he proposed a new kind of art-making centring on phenomenology and subjectivity as subjects unto themselves. Through his profound artistic inventions that use light and space as key materials, he cultivated a reputation as a visionary figure at the vanguard of what is known today as experiential art.

Irwin first exhibited with Pace in 1966, presenting his dot paintings at the gallery’s West 57th Street space in New York. He would go on to mount some 20 solo shows with Pace, maintaining a close friendship with the gallery’s Founder and Chairman Arne Glimcher, for almost 60 years. His legacy is deeply felt within and beyond Pace’s program, and his influence can be traced in the work of James Turrell, Mary Corse, Larry Bell, Keith Sonnier, Peter Alexander, and other artists who emerged from the Light and Space movement, as well as many figures of subsequent generations.

Irwin’s work is currently on view at Pace’s London gallery as part of the two-artist presentation Robert Irwin and Mary Corse: Parallax and A Desert of Pure Feeling, a new documentary tracing the artist’s storied career, is available to stream on Amazon and Apple TV. The film, co-produced by Glimcher, makes its European premiere at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London on October 26.

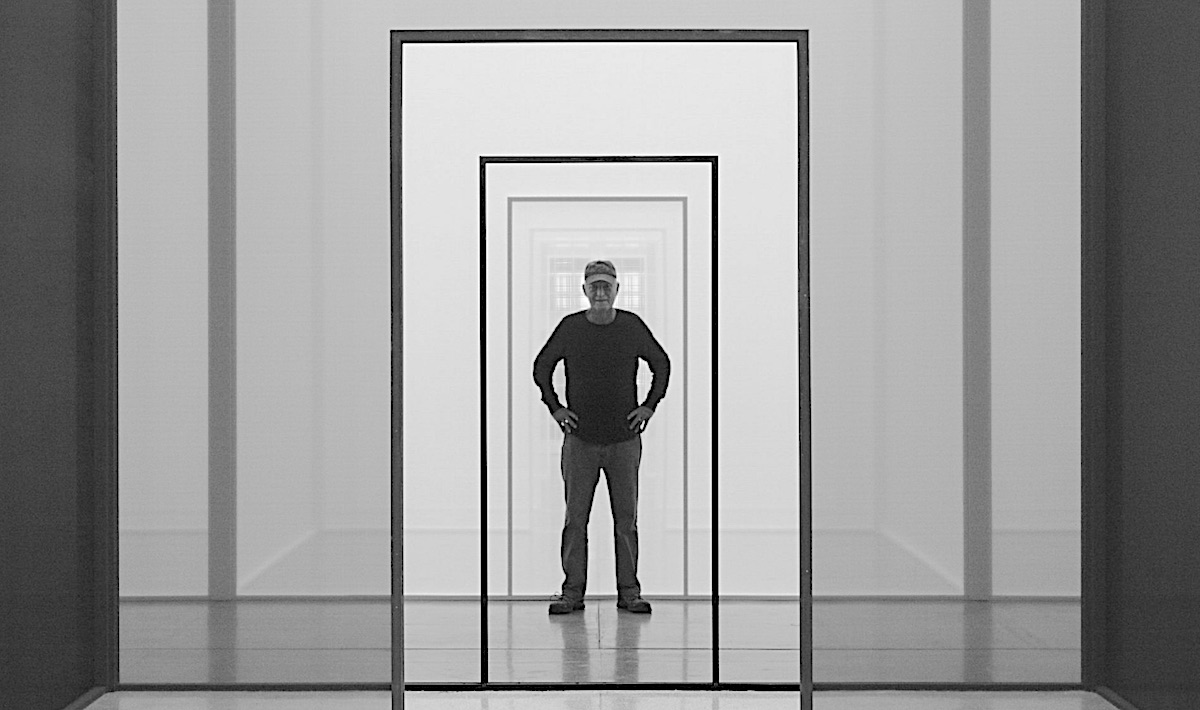

Top Photo: Robert Irwin Philipp Scholz Rittermann, 2013 Courtesy Spruth Magers