I knew Ross as a filmmaker, collaborator and the founder of the Funnel, the most important locale for experimental film in Canada. It wasn’t just the man’s charm, but his films — awkward, jarring, disjunctive, and, of course, ironic — which grabbed my attention. It was the late 1970s. It was punk. No one followed, everyone did what they weren’t expected to do. No reverence for commercial film, no desire for distribution. You made films because they needed to be made. Why not try it this way; let’s see what it looks like. A failure in film was a celebrated success.

The Funnel had begun quietly after the Crash ‘n’ Burn club had shut down in the fall of 1977

And there was Ross, a Sudbury boy in Toronto, recently graduated from the Ontario College of Art. McLaren began his career co-founding the Toronto Super 8 Film Festival, the first in Canada. His film Weather Building (1976) is emblematic of this period. Super 8, edited in camera, science fiction meets visual abstraction. It is a dissolving, collapsing, repeating visual. It is the antithesis of Warhol’s ponderous Empire State and a sly homage to Michael Snow’s incessant panning camera. With its off-screen sounds, footsteps, wind blowing, there is an uncomfortable energy in Weather Building, and simultaneously something very cerebral in its abstracted imagery. The film is an enunciation of the time.

It is 1976. McLaren is actively organizing screenings of films in the basement of the Centre for Experimental Arts and Communication (CEAC), a non-institutional, revolutionary art space operating at the edge of the edge. CEAC’s mastermind and director, Amerigo Marras, gay, young, was an architecturally trained anti-advocate for the status quo. He had grown up in radical Italian politics so, in the fresh cultural territory of Toronto art production, he was willing to open his cultural space to whatever was tough, Marxist, advocated world change, and had no time for history and its lies. Here, one was confronted. Here, in the art basement, McLaren created his seminal Crash ‘N’ Burn (1977), named after the short-lived downstairs punk club. With a wind-up 16mm Bolex, he films in silence a visual rendering of the rancorous. Jerky, rough, in grainy black-and-white, lead singer after lead singer takes off his shirt, gyrates, shakes his ass in the face of an audience who scream and jump up and down, up and down, their bodies, the camera. In the film, the audio is not synced to the visual, but this is seamless disjunction. The once-stars of early punk, the Dead Boys, Teenage Head, and the Diodes pass as McLaren zooms in and pans. It is a documentary, yet not. Scratches on the film reverberate with the snarling performers who want nothing more than to announce destruction, feign their own deaths, and draw knives across naked emaciated stomachs.The celluloid explodes in raucous frenzy: discordant, awkward, and pertinent. These are not folk singers, these are suffering punks who scream out to us: “I’m in a coma/Pull the plug on me/ I’m in a coma/please listen to me/I’ve got the right to live, I’ve got the right to die.” Isn’t this what it’s about? Kill me, it’s so fuckin’ boring.

While downstairs at CEAC the punks had screamed, five floors above Amerigo and crew organized an event for every day of the week and published Strike magazine. When Strike printed a grainy black-and-white-and-red cover photograph of Aldo Moro’s bloody body in May 1978, what occurred was a political firestorm in Conservative Ontario. Within days, all funding was withdrawn and the RCMP were at the doors. It was over in an instant. The art community went into a coma of fear; with hardly a word of protest in defense, CEAC collapsed. McLaren propels out of CEAC’s womb, tears off, landing at a small warehouse at the eastern end of Toronto where he finds a new home for the Funnel, an artist- controlled location for the making and the showing of film.

The Funnel had begun quietly after the Crash ‘n’ Burn club had shut down in the fall of 1977, operating in the CEAC basement rent-free until the 1978 incident.It was at the Funnel during the late 70s and throughout the 80s where those of us making films in the pure pleasure of self-indulgence found a supportive audience. Who cared that only a few saw your work as long as you were free to play with the media in every way possible, from over stylized narrative, to John Porter’s single frames of speed, or Michael Snow’s texts melting on found stock. It was the Funnel where you could create films for an uncompromising audience. Here, you could watch on a Friday night the latest efforts at the mutated incarnation of film. Here you could watch their films and meet some of the world’s most highly respected artists.

A who’s who of the avant-garde scene exhibited and discussed their work with appearances by Kenneth Anger, Robert Frank, Warhol Superstar Ondine, James Benning, Valie Export, Jack Smith. Ross organized, promoted and made it possible for everyone to create and show their films.

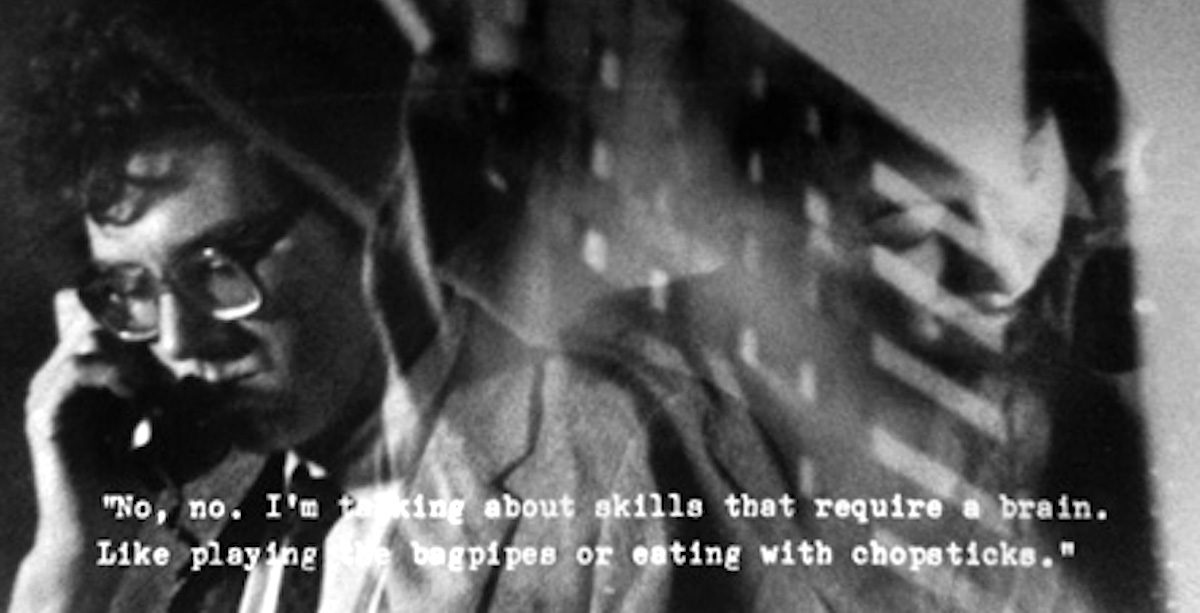

One of the first films McLaren showed at the new Funnel was Summer Camp (1978), called by the Globe and Mail’s Jay Scott: “One gruesome delusion after another. . . funny and grisly at the same time.” It is a banal, absurd film constructed of endlessly repetitive outtakes from a CBC audition for the cast of a television program, “Time of Your Life,” centering on youth culture. It is shot with a kinescope camera, an early hybrid video camera that recorded in 16mm film with an optical sound track. Each teenage actor undergoes a three-part audition: a short personal interview conducted by a prim CBC interviewer; a recital from memory of a fixed script; an improvisational dialogue with a hired CBC actor. The premise: the CBC actor portrays the brother dying of cancer. It is at this point, at the final stage of each audition, that the film takes a radical turn from a kitsch view of the amateur and the pathetic to the abject existential. The half-hearted, sweet questions of the interviewer, “What do you do in your spare time?” are replaced by the low voice from the hospital bed of the dying brother played by Peter Kastner (who later appears in Francis Ford Coppola’s You’re a Big Boy Now): “Can’t you do something to take me away from this place?” “The good times are over for us.” “It’s cancer in the final stages.” “I have three weeks to live.” So effective is Kastner that an auditioning teenager (who possibly studied in Stanislavsky technique) begins to cry, flowing tears. The humorous perversion of a 1964 CBC audition tape suddenly metamorphoses into existential angst. The banter, the empty dialogue, takes on signification: “It’s my life, it’s what I care about the most.” It is the punks again, screaming at the microphone about meaningless life and death.

Under McLaren’s direction, the Funnel was involved in the entire process of filmmaking; as important as the screening of films were the film classes and workshops. Throughout his career McLaren has been actively involved with a pedagogical approach to film. His teaching efforts began in the CEAC basement where he would run film workshops, and continue today with his active involvement in teaching film and video at a number of impressive schools in New York, at Cooper Union, Pratt Institute, Fordham University, and Millennium Film Workshop. It is this impulse to foster artistic talent which was at the core of the Funnel. Many filmmakers and artists had their first public exposure at the Funnel Gallery and screening room. Ironically, some of Ross’ students have gone on to make commercially successful feature films and have been nominated for Academy Awards.

McLaren has been steadfast in his “shrug-of-the-shoulders” rejection of the conventions of narrative film. Not-quite-orthodox structuralism, his films help in pointing to the possibilities beyond standard film conventions. A film he made in the late 1970s, Wednesday January 17, 1979 (1979) is a perfect example of the other possibilities of film. McLaren is working at the Canadian Film Distribution Centre cleaning up the heads and tails of films, taking off the old leader and adding fresh leader when he notices the leaders are often more interesting than the films. So, he splices them together, includes dates in rough Letraset, includes a final date in the future (Monday October 18,1988), and includes one three-second representational visual, part of a clock. It was all about appropriation, so why not the refuse from the waste bin, celluloid without an image, leaders brought together? And suddenly in the rhythm of the projector, in the scribbles and scratches, life appears.

McLaren’s microfiche film, 9×12 (1981), produced as an insert for Impulse magazine, is almost orthodox structuralism. Shot in the Funnel gallery space, the microfiche card consists of nine rows of 16mm film, 12 frames per row, which when placed together form a still image of the visual space and when projected display the space deconstructed through time.

In Sex Without Glasses (1983), a mannerist play on the Hollywood rear projection process shot, there is a scene where McLaren portrays himself floating above the world. With closed eyes the somnambulist filmmaker floats over a giraffe, over the moon, over the crawling insects, a shadow, a silhouette of the artist. It is film noir with irreverent humour. A man standing in a leather coat with eyes closed, the sound of rain, a black shadow passes, the man walks off screen. There is no sex, and hardly any glasses in this movie. But there are shadows in the background, rain in the dark, and many distant, barely visual, out-of-focus images which invoke a dark, postcard view of life and death. A woman looks at the sea, a man drives, Niagara Falls flows backwards, a man and a woman embrace in an erotic slide into the rushing water. In the final scene a young couple in bathing suits stand facing the ocean, she cups her hand and whispers into the boy’s ear, we don’t hear what she says, they walk off screen together. Sex Without Glasses is quintessential Funnel filmmaking; an abstract tale told with an implied narrative, seminal McLaren. It is film that employs visual effects, but primarily is constructed in existential bathos. There is humour, but in a deadpan abject colour. The dying brother in Summer Camp tries with futility to illicit sympathetic responses from his auditioning partners, but with amateur superficiality only receives incredulous attempts at sympathy: “You’ll be ok. It’s probably an error. You aren’t really dying.” But he is. The film leaders with their indecipherable text and scratches are the evidence of the ravishes of time on our waste bin-appropriated lives. McLaren may appear on the surface as humourous, repetitive, deadpan, but something is amiss, as the voices don’t sync with the visuals, so McLaren’s message isn’t about aesthetic breakage and formulaic manipulation, but finally about the water flowing backwards, the brother dying and the sexless bodies looking out into the artificiality of the process shot. — Eldon Garnet