The artist Susan Hiller has died age 78. Hiller will be remembered not only as a thinker and mentor, but as a powerful and unique voice in contemporary art over the last four decades. Her investigations and revelations of the hidden depths of human imagination found their expression in installation, film, painting, writing, sculpture and photography.

A powerful and unique voice in contemporary art over the last four decades – Lisson Gallery

Born in Tallahasse, Florida in 1940, Susan Hiller studied anthropology in the US, before moving to the UK in the 1960s where she began her career as an artist. Here she innovated the use of multimedia technologies, becoming a pioneer of installation and video art. Her work explored aspects of culture that were marginalised, repressed or overlooked, from postcards, domestic wallpapers and other everyday materials, to paranormal phenomena such as automatic writing, telekinesis, and supernatural encounters – an area of investigation that she designated ‘paraconceptual’.

Beginning her artistic practice in the early 1970s, Susan Hiller was influenced by the visual language of Minimalism and Conceptual art and later cited Minimalism,

Fluxus, Surrealism and her study of anthropology as major influences on her work Hiller’s first exhibition was a group show at Gallery House in London in 1973.

There she presented two works, one under her own name and one using the pseudonym ‘Hace Posible’ (Spanish for ‘make it possible’); Transformer, 1973, a floor to ceiling grid structure with tissue paper covered with the artist’s marks, and Enquires, 1973, a slide show of facts collected from a British encyclopaedia meant to emphasise culturally partisan definitions in what is considered an objective and equitable source of information. Her artistic practice was innovative for her time and included a variety of media and performance-based work.

In the early 1970s Hiller created participatory ‘group investigations’ including Pray/Prayer (1969), Dream Mapping (1974) and Street Ceremonies (1973).These works originated in her conviction that “art can function as a critique of existing culture and as a locus where futures not otherwise possible can begin to shape themselves.”

Over the course of her career, Susan Hiller became known for making use of everyday phenomena and cultural artefacts from our society, drawing inspiration from sources as diverse as postcards, dreams, automatic writing, archives, Punch & Judy shows, UFO sightings, horror movies and narratives.[10] Using the techniques of collecting and cataloguing, presentation and display, she transformed these everyday pieces of ephemera into art works that offer a means of exploring the inherent contradictions in our collective cultural life, as well as the individual and collective unconscious and subconscious. As an artist, she was interested in the areas of our cultural collective experience that are concerned with devalued or irrational experiences: the subconscious, the supernatural, the surreal, the mystical and the paranormal. She engaged with such experiences and phenomena which defy logical or rational explanation through the rational scientific techniques of taxonomy, collection, organisation, description and comparison. She did not, however, apply systems of judgment to the work, refraining from ever categorising the experiences as ‘true’ or ‘false’, ‘fact’ or ‘fiction’.

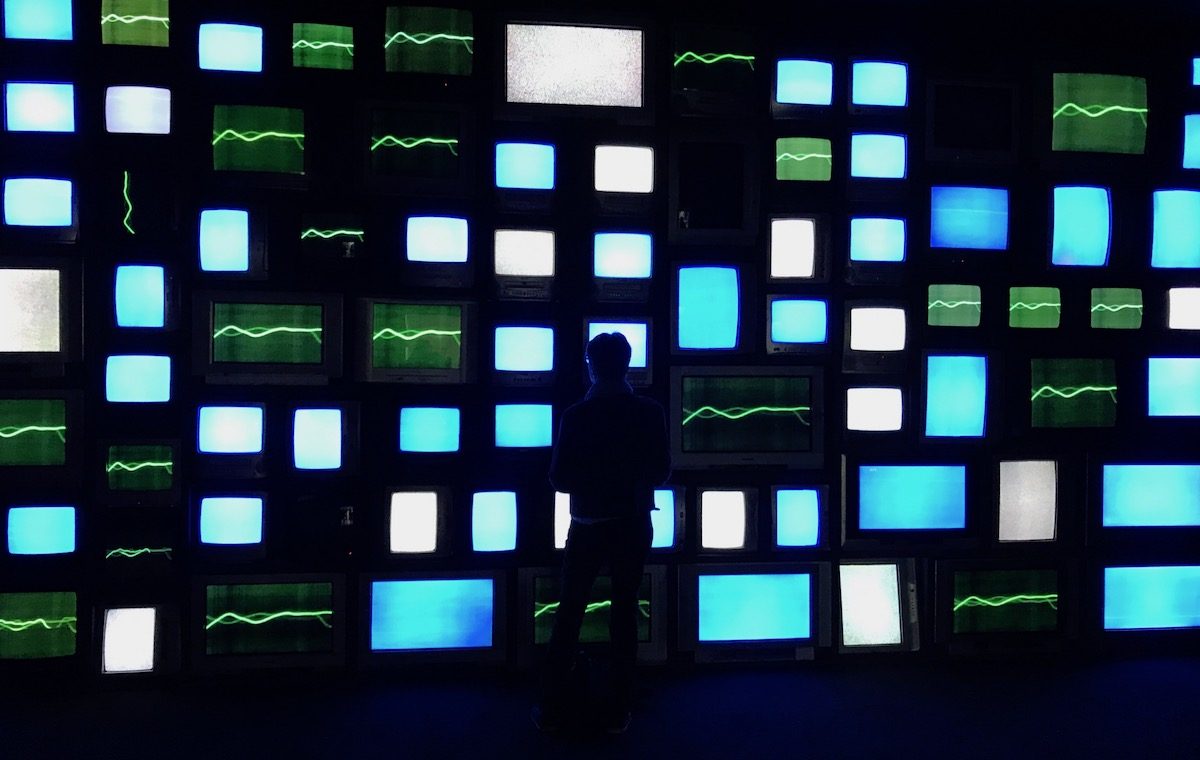

Hiller described her practice as ‘paraconceptual’ a neologism that places her work between the conceptual and the paranormal. Many of her works explore the liminality of certain phenomena including the practice of automatic writing (Sisters of Menon, 1972/79; Homage to Gertrude Stein, 2010), near death experiences (Clinic, 2004) and collective experiences of unconscious, subconscious and paranormal activity (Dream Mapping, 1974; Belshazzar’s Feast, 1983-4; Dream Screens, 1996; PSI Girls, 1999; Witness,2000). Borrowing strategies from Minimalism to apply a “rational” framework to these products of the unconscious, the artist mounted the work “Sisters of Menon” in four L-shaped frames that, when installed on the wall together with four individually framed pages of her own commentary, make a cruciform. Hiller also published Sisters of Menon as an artist’s book. She insisted on blurring the boundaries between cultural definitions of “rational” and “irrational,” at the same time reinstating the validity of the unconscious as a source of knowledge or truth.

After the mid-1970s, Hiller continued her engagement with Minimalism. For 10 Months (1977–79), she took photographs of her pregnant body and kept a journal documenting the subjective aspects of her pregnancy. The final work comprises ten gridded blocks of twenty-eight black and white photographs, each block corresponding to a lunar month. The images are accompanied by excerpts from her journal entries for the same period. These components are installed on the wall in a stepped pattern that descends from left to right. As Lisa Tickner observed, “The sentimentality associated with images of pregnancy is set tartly on edge by the scrutiny of the woman/artist who is acted upon, but who also acts: who enjoys a precarious status as both the subject and the object of her work…The echoes of landscape, the allusions to ripeness and fulfilment, are refused by the anxieties of the text, and by the methodical process of representation.” The work was considered controversial when first exhibited in London.[2]

Beginning in the 1980s, Susan Hiller incorporated the use of audio and visual technology as a means of investigating these phenomena, allowing the visitor to ‘make visions from ambiguous aural and visual cues’. In describing Hiller’s work, art historian Alexandra Kokoli notes that “Hiller’s work unearths the repressed permeability … of … unstable yet prized constructs, such as rationality and consciousness, aesthetic value and artistic canons. Hiller refers to this precarious positioning of her oeuvre as ‘paraconceptual,’ just sideways of conceptualism and neighbouring the paranormal, a devalued site of culture where women and the feminine have been conversely privileged. In the hybrid field of ‘paraconceptualism,’ neither conceptualism nor the paranormal are left intact … as … the prefix ‘para’ -symbolises the force of contamination through a proximity so great that it threatens the soundness of all boundaries.”

Hiller’s ceaseless engagement with language and dreams combined unswervingly in her often-visionary practice and she is perhaps best known for large-scale works of conceptual clarity, technical complexity and formal elegance, such as the epic archival display From the Freud Museum (1994), the multitudinous voices of Witness (2000) and the historical mapping of The J. Street Project (2002-05). She also remained a staunch advocate of the work of many fellow female artists throughout her life and taught extensively in London, Los Angeles, Belfast and Newcastle.

In addition to showing at subsequent editions of Documenta (2012, 2017) and the Sydney Biennale (1982, 1996, 2002, 2010), over the last two years Hiller had major solo exhibitions in Turin, Vancouver and Miami and she was recognised by a major retrospective at Tate Britain in 2011, curated by Ann Gallagher, who said yesterday that, “Susan Hiller significance and influence as an artist is immense and will undoubtedly only increase over time, but her presence, her sharp intellect, her wisdom and her friendship will be much missed by so many.”