On the surface it hardly seems fair to compare Brazil, a vast country of 200 million people, to Hong Kong, a city of ‘only’ 7 million. Yet upon closer examination, patterns between the two emerge, that allow for comparisons to be made and conclusions to be drawn. The foremost purpose of this article is to compare Brazil’s contemporary art market, centred in the cities of Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo and Belo Horizonte, to that of Hong Kong.

The past two years have paved the way for a new exchange in art between Hong Kong and Brazil, and between Hong Kong and São Paulo in particular. Whilst characteristically different in terms of medium and vigour of expression, the art industries of Brazil and Hong Kong are both currently benefitting from a sudden surge of invested public interest, occurring amidst a mutual period of rapid economic development and social change. Vibrant and exotic in their own unique ways, host to tropical fantasies of colours and carnivals, rich in postcolonial sophistications and conflicting cultural heritages, Brazil and Hong Kong are two of the most sought-after focal points in the contemporary global art market.

It is fascinating to see that connecting exhibitions are now shown simultaneously by host galleries in Hong Kong, Brazil and London, such as with Gilbert & George’s London Picture Series (White Cube), and Simon Lee Gallery’s recent show ‘In Lines and Realignments’ involving six Brazilian artists (including conceptual artist Cildo Meireles) in London and Hong Kong. White Cube and Simon Lee Gallery opened their first Asian exhibition spaces within a month of each other in Hong Kong in 2012 (White Cube on March 2nd and Simon Lee Gallery on April 2nd), while White Cube opened its third gallery in São Paulo that very same year on December 1st.

Hong Kong recently achieved 3rd place in international art sales, after New York and London, reflecting the market’s appetite for contemporary art sold in Hong Kong. In May 2013, ‘Hong Kong International Art Week’ drew a full crowd ranging from art-lovers to curious onlookers, to the inauguration of Art Basel Hong Kong. That very same week also saw the hosting of the Asia Contemporary Art Fair – whose founders also started the Hong Kong Young Artist Prize in 2012 and the Hong Kong Art Prize in 2013 – as well a dockside visit by Florentijn Hofman’s giant floating yellow rubber duck, photographs of which inundated social media for weeks after. Hong Kong had proven itself capable of hosting global contemporary art sales.

Parallel to these events in Hong Kong, in Brazil March 2013 saw the opening of MAR (Rio Museum of Art), Casa Daros (Ruth Schmidheiny’s exhibition of her collection of South American artists), and the new building of the USP (São Paulo University) Contemporary Art Museum; the opening of the philharmonic building Cidade das Artes in Rio in May and the Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil in July. This upsurge in energy was also joined by new galleries, magazines, publishers, bookshops, and the launching of new art awards in conjunction with ongoing biennales in São Paulo, Porto Alegre (Bienal do Mercosul) and Curitiba (VentoSul), and anticipatorily in Bahia in 2014.

However, Hong Kong’s modern cultural development is obviously divergent from that of Brazil. While Hong Kong’s privately-developed, market-oriented West Kowloon Cultural District continues to fiddle with its still-empty parcel of land, juggling a temporary mix of outdoor exhibitions, festivals, and concerts (West Kowloon Bamboo Theatre, Clockenflap, Freespace Festival, Inflation!), Brazil has taken great strides in using art to raise social awareness at the grassroots level. It is clear that Hong Kong has a lot to learn from Brazil’s example. Take, for instance, Bernardo Paz’s INHOTIM / Institute of Contemporary Art and Botanical Gardens in Minas Gerais. Over the past 7 years the Institute has garnered positive environmental reviews by integrating its buildings into 100 lush hectares of surrounding national park. Rather than serving as a space for financial speculation, the Institute promotes art as a vehicle for economic, social and cultural development – an inspiring attitude that underlies much of contemporary Brazilian art. This is reflected in everything from the materials used to the initiatives taken by the Institute, and by their permeation into surrounding communities. Cultural activities, professional training, and educational programs help gather human resources needed to harness the energy to fulfil this urgent sociocultural priority.

The dense intertwining of social media platforms has given artists the power to move millions of people now more than ever before, even if their work is only ever read or seen on phone and computer screens. One such artist is Vik Muniz, whose project in the world’s largest landfill site, Jardim Gramacho in Rio where “the garbage from the millionaire’s mansion mixes with the garbage from the poorest favela”, is depicted in the documentary film ‘Wasteland’ and subsequent series ‘Pictures of Garbage’ (2008). In it, a small group of garbage pickers are selected to take part in creating their own portraits, which Muniz had captured on the landfill site, some by mimicking famous Old Masters paintings. The money raised from auctioning off the portraits (US$250,000 altogether) was split amongst each project participant, and enabled substantial, long-lasting improvements in their daily lives. The mere act of involving them in the artistic process, using the same materials they worked with everyday, gave the workers an opportunity to see themselves differently, as part of a greater work, and despite the difficult conditions and circumstances gave new value to the lives they led. This realization alone gave them insight into their own strengths and restored their dignity and self-respect as individuals.

Another great example of the positive social power of art is the outdoor photography exhibition entitled ‘Women are heroes’ by French artist JR in São Paulo, who took close-up photographs of the faces of different women living in the slums or favelas, printed them to an enormous scale, laid them out over rooftops, along walls, and inlaid them in stairways – places where women in particular, being more bound to their homes, have to endure constant discrimination, repression, and threats of expulsion by government and property developers (their male counterparts being more likely to seek work outside the favelas and thus largely absent).

Those engaging in street art, “the largest art gallery in the world”, accessible to all without exception, like with JR’s photography project, also have the ability to directly reach the eyes of those who don’t normally attend museums and galleries. While addressing sometimes dire, heartfelt issues, these well-known works have more impetus to move the public to action than the people and the issues themselves.

Both Hong Kong and Brazil face a widening social gap. While we may celebrate our cities’ newfound cultural cachet and embrace our own overinflated egos, and while those in the cultural sectors may benefit from higher value art sales, our unsustainable economic trajectories breed ever-greater inequalities, with more resources concentrated in ever-fewer hands. This seriously threatens low-income earners, including artists themselves. In conversation with Régis Durand from L’Architecture D’Aujourd’hui, Brazilian artist Vik Muniz said:

“No other sector of the economy is in greater need of a tax reform and if a political will to act is not present at this turning point, our role as players in this great cultural arena will once again be reduced to that of simple consumers and transmitters of foreign trends. A country speaks through its culture and it does it best when it is not being stifled by inefficient regulations and bureaucracy”.

Needless to say, this applies not only to Hong Kong and São Paulo but also to cities and countries all over the world. There is a global outcry over the need for governments worldwide to reduce inequality, uphold human rights, and improve the livelihood of their citizens and communities. This is what some of the highest-impact artworks of the future will speak about and receive global attention for.

There could definitely be a lot more urban art in Hong Kong. Referring back to Florentijn Hofman’s giant floating duck, never before has a piece of art permeated all levels of Hong Kong society so quickly and effectively. Hong Kongers are slowly becoming more aware and inspired to take the leap from passively enjoying and taking pictures of visiting internationally sourced artists and artworks, to actively engaging in the creative process themselves. Without a doubt, the more the public are exposed to outside talent and artistic processes, the more the art will open up their imagination and tap their yearning to express themselves. It is one way that skills, thoughts, and creative energy could be integrated and applied to the challenge of stimulating society in a positive way.

This is the major difference between the art sales of Hong Kong and Brazil: a large proportion of what is sold in Brazil is by local artists. As a representative of toof [ contemporary ] gallery in Hong Kong, our contribution to the collective creative process is in exposing the Hong Kong public to a greater range of art, and, through hosting workshops by the artists themselves wherever possible, to help bridge the degree of connection and access to what we are showing. Though we do not exclusively show Brazilian art, it is a definite fixture for us as a source of inspiration and collaboration of our times.

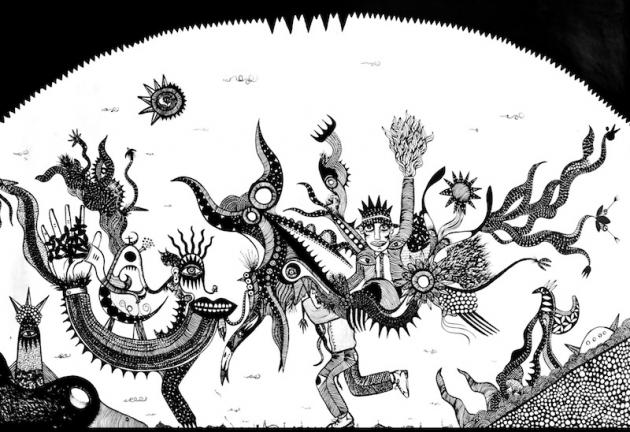

Words: TIFF CHAN Image: Electric Convoy, by Guilherme Kramer 2013, 121×80.5cm Indian ink on Aquarelle Paper

Of the Brazilian artists we are representing at toof [ contemporary ] from our art, food, design and culture platform in Hong Kong, those more inclined to urban/ street art include Guilherme Kramer, Alexandre Orion, Speto and Rafael Hayashi. We will also curate exhibitions with Gisela Motta and Leandro Lima in the coming year.