Soo Catwoman, a Punk style icon of the 1970s, has died at the age of 70. With her shaved skull flanked by two sharp black tufts of hair — feline, defiant — she became one of the most recognisable women in British punk. Her look and the attitude that came with it helped define a moment when rebellion was visual before it was verbal.

Born Susan Lucas, she died in London on September 30 at the age of 70. Her daughter, Dion October Lucas, said the cause was complications from meningitis. The story of her transformation remains one of punk’s great origin myths. In 1976, in suburban Ealing, she asked a baffled barber to shave out the middle of her cropped hair, leaving two tufts like animal ears. He hesitated — “I think he thought I was joking,” she later said — but did it anyway. She greased the tufts upright with Vicks VapoRub, dyed them black, and named herself anew. In a single act, she invented a look that would outlive the scene that birthed it.

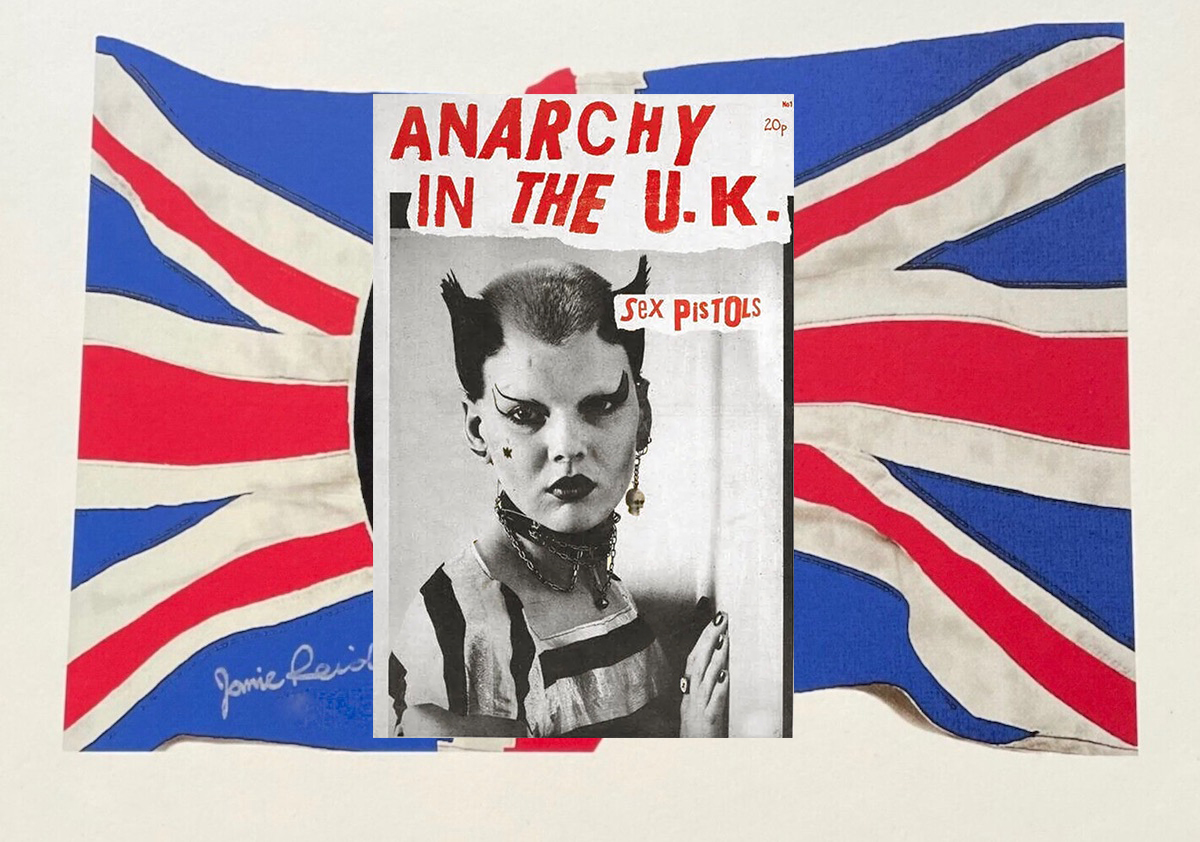

That summer, she fell in with Sid Vicious and Johnny Rotten at Club Louise, one of those underground crucibles where punk’s future was being thrashed out between songs and fights. She soon appeared on the cover of Anarchy in the U.K., a Sex Pistols fanzine — an image that would be copied endlessly, with and without her consent. Her face became shorthand for punk’s beautiful chaos: cat-like, amused, untouchable.

The media christened her “the female face of punk.” She never asked for the title but wore it with quiet pride. Her likeness was reproduced on posters, T-shirts and magazines across Britain — often without her knowledge or payment. “My face and image, my ‘art,’ as some have called it, has been hijacked,” she once said. Still, she recognised the irony: her anti-fashion had become fashion itself.

In the years that followed, her image inspired fashion designers such as Vivienne Westwood, Thierry Mugler, and Junya Watanabe. Keith Flint of The Prodigy famously styled his acid-green horns after her hair. Mark Perry, in And God Created Punk, called her “the sexual opposite of Johnny Rotten,” a kind of punk Venus who embodied attitude without imitation.

Born Susan Helene Lucas in 1954, the tenth of fifteen children, she grew up in Chiswick in a working-class family where space was tight and imagination expansive. As a teenager, she was drawn to the flamboyance of glam rock — Bowie, Bolan — but when punk arrived, she saw something truer: rougher, less rehearsed, and hers for the taking.

By her twenties, she was a fixture in the London scene, photographed alongside Billy Idol and members of The Damned. She made music, too — backing vocals for The Invaders’ Test Card album in 1979, and later a cover of The O’Jays’ Back Stabbers with Derwood Andrews and Rat Scabies. But unlike many of her peers, she never chased fame. When punk turned fashionable, she slipped away.

“The people who once crossed the street to avoid me,” she said, “started buying the clothes I wore.” Her later life was quieter, marked by motherhood, activism, homeschooling, and an enduring sense of humour. Beneath the black eyeliner and safety pins, she was, her daughter said, “a hippie underneath it all” — someone who believed rebellion began in thought, not destruction.

When her image resurfaced decades later, she embraced it with a sense of irony. “It still seems strange to me,” she wrote, “that what happened back then could bring about so many changes — in hair, music, fashion. What started as anti-fashion became fashion in itself.”