In a bold and meticulous act of historical fabulation, Pablo Bronstein has turned his attention to one of the most elusive architectural enigmas in religious history: the Temple of Solomon. Presented within the storied interiors of Waddesdon Manor, this new series of paintings on paper approaches the legendary structure not as archaeology but as an aesthetic mirage—a prism through which past and present obsessions with grandeur, ritual, and empire are refracted.

Titled The Temple of Solomon and its Contents, the exhibition is Bronstein at his most erudite and mischievous. Drawings range from austere cross-sections to frenzied frieze details, from imagined aerial layouts to elaborately embellished Solomonic columns. The Temple here is not a single form but a hall of mirrors, drawing on centuries of failed attempts to visualise a building described in scripture but never conclusively seen.

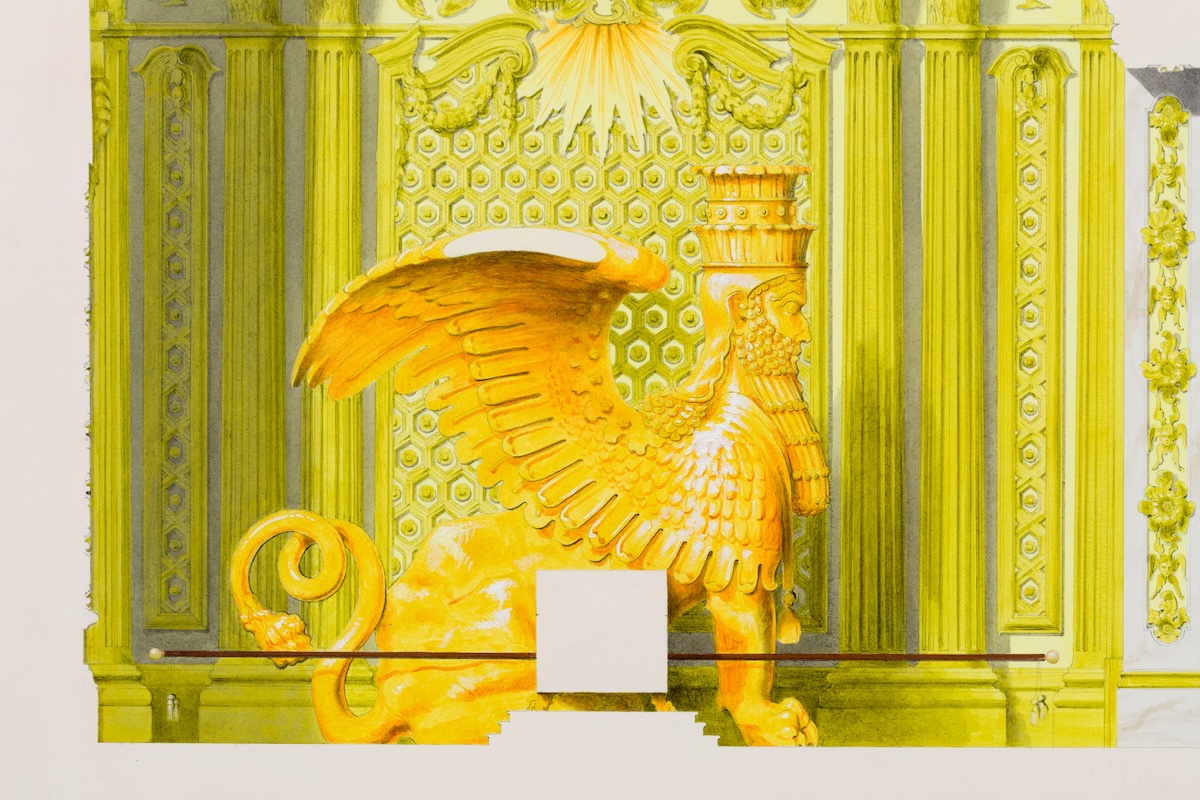

Pablo Bronstein, Temple of Solomon (first version): Facade 2024-2025 ©Pablo Bronstein, Courtesy of the artist and Herald St, London, Photo by Jack Elliot Edwards

Suppose Waddesdon once functioned as a stage for Rothschild cosmopolitanism and elite collecting. In that case, Bronstein’s Temple renders a different kind of opulence—one that speaks to the Western architectural imagination’s recurring urge to claim antiquity as its own. In his hands, neoclassical and baroque vocabularies jostle with Romantic fantasy, all filtered through the stylised clarity of 18th-century architectural draughtsmanship. Bernini, Blondel, Soane, John Martin—they all echo here, ghosts in a paper temple of impossible precision.

Bronstein, who was born in Buenos Aires and grew up in London, has long deployed architectural pastiche as a critical tool. What makes this series so resonant at Waddesdon is the artist’s sensitivity to the Manor’s cultural context. Responding to its identity as a Jewish country house, Bronstein draws a subtle thread between the Temple’s mystique and the aesthetic politics of diasporic display.

Inside his Temple, we find not only imagined exteriors but imagined contents: seven-branched menorahs in gold, the Ark of the Covenant, and the bread-laden table of the Divine Presence—all rendered with a theatrical seriousness that edges into satire. His interest is not in reconstruction but in projection: what these images reveal about those who create them. “The Temple,” he notes, “has had more than its fair share of reimaginings in the style of the times. These are often naive, often grandiose. That is precisely their allure.”

Pablo Bronstein, Temple of Solomon (first version): Cross Section 2024-25 ©Pablo Bronstein, courtesy of the artist and Herald St, London. Photo by Jack Elliot Edwards

The exhibition is enriched by Bronstein’s curated selection of rare architectural drawings and design books from Waddesdon’s collection—materials that reveal the extent to which ornament, ritual, and ideology have always converged in both the domestic and the sacred. Alongside these are 18th-century embroidered hangings from the Rothschild Collection, depicting both the First and Second Temples. Their inclusion anchors the show in a longer Jewish visual tradition while highlighting the artist’s deft interweaving of aesthetics and theology.

Director Pippa Shirley describes the show as “serious and playful, learned and fantastical”—a duality that captures Bronstein’s practice perfectly. This is not didactic historicism but a glorious, high-stakes game of style and scale. At its core is a question that lingers long after viewing: not what the Temple of Solomon was, but why we so desperately wish to see it.