A challenging and intelligent new show at Tate Modern asks rather more questions than it actually succeeds in answering. It is, nevertheless, something of a landmark event. As somebody of Caribbean origin (going back to the year 1635) but of white ancestry (yes, I had my DNA analysis done quite recently) I suppose I am simultaneously both well and badly qualified to comment on the show, Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power.

The show represents a search for and deliberate re-creation of this lost Black identity – ELS

The difference between Black culture in the Caribbean and the form in which it exists and is recognised in the United States is simple but often overlooked. In Jamaica, where I come from, for example, the population is more than 90% black. In the United States, in contrast to this, African Americans are a large, visibly different minority.

It is not even certain that they are now the largest minority – it looks as if the African American population of the USA has been recently outnumbered by the Latinos, though these are so much divided among themselves that it is hard to be sure. Then, too, there is the fact that many impeccably American Latinos – not first-generation immigrants but ‘born y’a’ – as we say in Jamaica have their own share of African ancestry. It’s their choice whether they identify with Latino culture or with African American culture. It’s a little difficult to do both. This dilemma exists particularly for immigrants from Cuba and their descendants, and also for much of the population of Puerto Rico.

If you look through the catalogue of Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power you are struck by the fact that there are very few Spanish – i.e. Latino-sounding names. Virginia Jaramillo, yes – and maybe Roy DeCarava. Most of the surnames are English: Kay Brown, Ed Clark, Bob Crawford, Jeff Donaldson. If these names were simply thrown at you, outside of the context provided here, you’d never guess that the bearers might be of African descent. Just occasionally an adopted name – e.g. Senga Nenguidi – provides a clue. This very fact points to the way in which African identity was stripped away by the mechanisms of slavery. Those brought from Africa to America to be sold as slaves were deliberately stripped of every trace of their original cultures. All they had left, in the most literal sense, were their black skins.

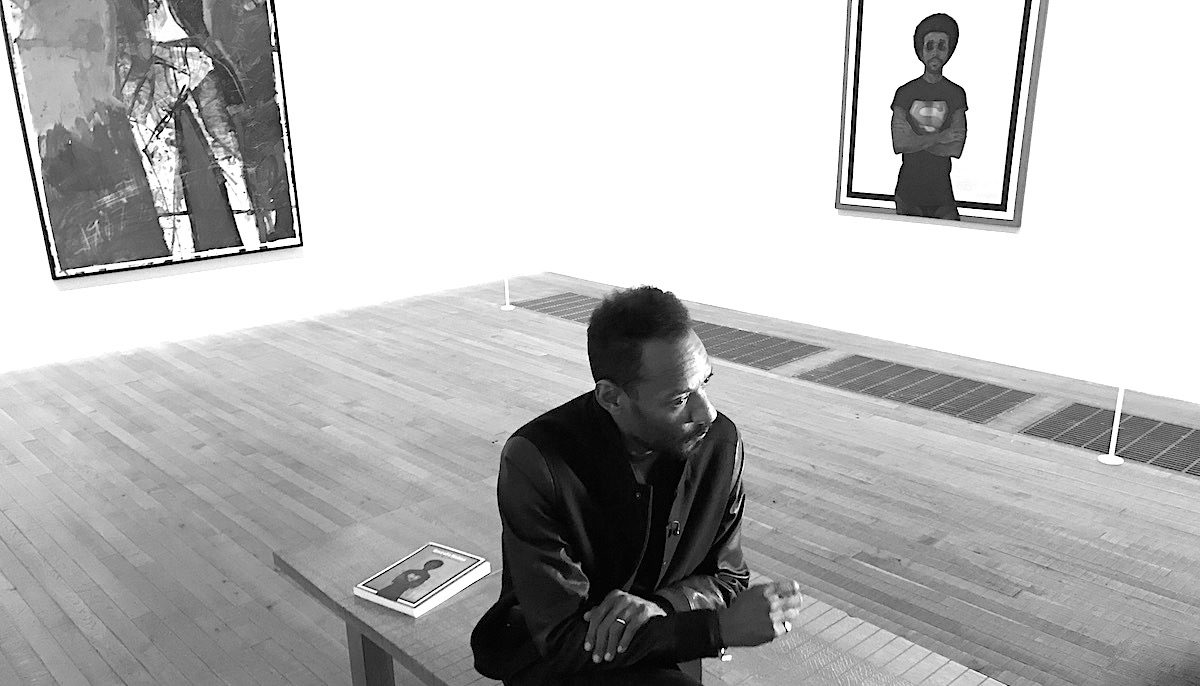

What is deeply moving about the exhibition is the fact that it represents a search for and deliberate re-creation of this lost Black identity. It is a defiant statement of separateness, and of separate worth. One made within the context of American contemporary culture seen as a whole.

There is yet another irony operating here, which is that American culture, particularly in terms of the visual arts, has, since the gradual decline of the Pop Art movement, become more and more regional. It is much easier to define Californian art, or Mid-Western (specifically Chicago) art, or art from New Mexico or from New Orleans or from Seattle, than it is to point at some recent artwork or art phenomenon and say ‘Yes, that’s typically American.’

A curious consequence of this era of cultural fragmentation in America is that two things that used to seem very isolated and even specialised, have increasingly come to be perceived as quintessential American statements of identity. One is Feminist art, though this is a risky belief when one looks at the difference between, say, the work of Judy Chicago, the matriarch of American feminism in art, and that of a new generation take-no-prisoners female photographers working in Iran: take-no-prisoners but keenly aware of the complex role played by women in the whole history of Iranian culture. The same thing is true in Japan. The other is, sure enough, African American art. When you go to the Venice Biennale, for example, it is more than likely that you will find a black artist occupying the American pavilion.

The exhibition offers work by a number of striking figurative artists, not as well known outside the USA as perhaps they ought to be. Among them are Barkley L. Hendricks, with a wonderfully naughty nude self -portrait entitled Brilliantly Endowed, and Norman Lewis’s America the Beautiful – at first sight a black-and-white abstraction, on a closer look a panoramic representation of a Ku Klux Klan procession. Equally striking are the body-image works – images made by pressing a greased body to the canvas. A famous example, present here, is David Hammons’ Injustice Case, showing a bound figure on a chair, framed by a cut-to-ribbons American flag. This image refers to Black Panther co-founder Bobby Seale’s trial for conspiracy of commit violence – “during which Seale was bound and gagged in the courtroom”. Equally memorable is Betye Saar’s The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, satirising the condescending vision of black womanhood, promoted commercially to the white audience as an image of “warmth, love, and trust” Saar’s Aunt Jemima holds a broom but is reaching for a gun. There is also lots of good reportage photography.

America the Beautiful, though not, in fact, an abstract painting, is, however, forcibly slotted into a questionable section of the show, devoted to the idea of Black Abstraction, a notion vigorously defended in a major catalogue essay by Mark Loving. I’m afraid my reaction to this is “I believe you, thousands wouldn’t”. Once figuration is ruled out, the idea of Black art loses its point. You have to be told that what you are looking at is the work of a black artist, with an indistinguishably Caucasian name, expressing ideas about race. Off-stretcher abstract paintings, offered here as typical of African American artistic expression, are no such thing. They have been made in America and elsewhere in quite a number of other contexts. African American art has no special priority in this form of expression.

Equally questionable is the omission of the artist who is currently the best known (and most expensive) American artist of African descent, Jean-Michel Basquiat. Basquiat was born in 1960 and died, aged 27, in 1988 – five years beyond the time-span surveyed at the Tate. But he was an unusually precocious figure, first as the New York graffiti artist SAMO (an abbreviation for Same Old Sh*t), in partnership with his friend Al Diaz, later as an extremely well-connected young painter, exhibiting in major galleries, sometimes working in collaboration with Andy Warhol, who is present in the Tate show where Basquiat isn’t. In 1980 he participated in the epoch-defining Times Square Show. He had his first one-man exhibition at the Annina Nosei Gallery in New York in 1981. Next year, he was showing regularly in the company of the major names of the time, Julian Schnabel, David Salle, Francesco Clemente. He was, by 1983, represented by Gagosian in Los Angeles and by Bruno Bischofburger through Europe.

He was by no means indifferent to the issues about race than are raised by Soul of A Nation at Tate Modern. A painting from 1981 is entitled Irony of a Negro Policeman. Another, very ambitious composition from 1983 is called simply Untitled (History of the Black People.

Very soon there will be a major Basquiat retrospective (the first of its kind in the UK). It is entitled Boom for Real and opens at the Barbican Art Gallery on 21st September. It overlaps neatly with Tate Modern’s Soul of A Nation, which doesn’t close till 22nd October. If you want the complete story, better see both.

Words: Edward Lucie-Smith Photos: Paul Carter Robinson © Artlyst 2017

Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 12 July – 22 October 2017 Tate Modern, Level 3, Boiler House