‘Can We Stop Killing Each Other?’ is, in the words of Jago Cooper, Executive Director of The Sainsbury Centre, a “wide-ranging exploration of human value systems, of how we decide what is right and wrong, [which] brings out that most radical, hopeful and unique ability of our species – human empathy.”

This is the latest in the Sainsbury Centre’s radical exhibition programme, which explores the big issues in contemporary society. Can We Stop Killing Each Other? is a series of exhibitions that include an installation by Aotearoa/New Zealand artist Anton Forde, a series of new paintings reflecting on the refugee crisis by Ethiopian artist Tesfaye Urgessa; presentations of historical artworks such as Claude Monet’s ‘The Petit Bras of the Seine at Argenteuil’, and an exhibition spanning Shakespearean tragedy to Hitchcockian spectacle, which asks questions of violent stage and screen narratives, plus (still to come, in November) ‘Seeds of Hate and Hope’ highlighting personal artistic responses to global atrocities, such as genocides, ethnic cleansing, war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Given that, according to the Global Peace Index 2024, one hundred countries have been “at least partially involved in some form of external conflict in the past five years, up from 59 in 2008”, this is a timely series of exhibitions.

The Sainsbury Centre’s radical exhibition programme is based on the understanding that art not only addresses fundamental societal challenges but also engages people with the fundamental questions of life. As such, he argues, regarding this exhibition series: “The emotional power of art to generate empathy and understanding is what enables us to explore the world around us from a completely different perspective. This is what makes these exhibitions so resonant and impactful. They bring into sharp relief our ability for compassion, sensitivity and hope; some of the best defining traits of what makes us human.”

Tiaki Ora Protecting Life_Photo Kate Wolstenholme_20

Before descending to The Sainsbury Centre’s cavernous basement exhibition spaces, we are invited to explore Anton Forde’s monumental installation of 81 over life-size figures, entitled ‘Papare Eighty.one’. Presented in a defensive V-shape inspired by the united flying formation of migratory birds, the wooden figures (pou), hand carved by Forde at 8.2 feet tall, wear Kākahu/cloaks woven by kaiwhatu (traditional Māori weaver) Shiree Reihana – which elevate the honour of the individual pou and the collective work – as well as a Pounamu/nephrite teardrop necklace, seen as a token of sympathy and shared emotion. The large figures stand in peaceful solidarity to protect the smallest pou located at the rear of the defensive formation.

This work was inspired by the peaceful actions of the pacifist Māori community at Parihaka, New Zealand, in November 1881, in the face of a British colonial invasion, as well as the many examples of similar powerful peaceful responses worldwide that have been inspired by Parihaka. It is a call for kotahitanga: unity, togetherness and solidarity. It shows that collective action can safeguard the future of our communities for generations to come, without the need for killing, both physically and culturally.

‘Can We Stop Killing Each Other?’ begins with pacifist solidarity and ends in peaceful contemplation of sanctuary and a safe home. Monet spent a year in voluntary exile in England and the Netherlands during the Franco-Prussian War, returning to France in 1871, where he settled in Argenteuil near the river Seine. There, having found a sense of stability and home, his artwork flourished as he created paintings inspired by his surroundings, such as ‘The Petit Bras of the Seine at Argenteuil’. This painting, part of The National Gallery Masterpiece Tour 2025–27, is here exhibited in a multi-sensory reflective space which encourages peaceful contemplation. It is the ideal end to exhibitions exploring our violent tendencies and highlights art’s underlying propensity towards sustained contemplation and reflection, even when at its noisiest and most strident.

In between these two bookends, ‘Can We Stop Killing Each Other?’ explores the roots of rage and resilience. ‘Thou shall not kill’ is the sixth commandment in the Old Testament of the King James Bible. This condemnation of killing is found in Christianity, Judaism and Islam, and the principle of ‘non-violence’ is central to Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism and Sikhism. Although religion and culture tell us that killing is wrong, violence remains prevalent within many people’s reality and contributes in large part to what is consumed through the media. Some would also, of course, argue that religions are the cause of that conflict.

Religious and secular texts and the art inspired by them are often dual-edged in that they can be read either as glorifying/supporting violence or subverting it. This is essentially the debate that is explored or initiated by these exhibitions whether they are examining stories from the Bible (Luca Giordano’s ‘The Brazen Serpent’ and ‘The Judgement of Solomon’), puppetry and theatre in different cultures (Britain, India, Indonesia, and Japan), Shakespeare’s plays, or films, including thrillers (‘Crossfire!’ by Christian Marclay) and horror, such as Hitchcock’s ‘Psycho’ (‘24 Hour Psycho‘ by Douglas Gordon). The question posed is whether our focusing on violence leads us to act violently ourselves or serves as a warning to eschew violence and pursue peace.

Luca Giordano, The Brazen Serpent, c.1690, oil on canvas © Compton Verney, photography by Jamie Woodley

Giordano’s two images show scenes in which the instrument of death becomes the source of justice or healing. ‘The Brazen Serpent’ is a bronze replica of the snakes that poisoned the Israelites in the wilderness, while on their journey to the Promised Land. When the Israelites looked at the bronze serpent, they were healed. In the story illustrated by ‘The Judgement of Solomon’, the threat of violence to a child is used to identify the child’s real mother from the other, also claiming ownership of the child. In these images, harm or death is threatened but not delivered, and peace is ultimately restored.

In writing about ‘A Grim Fascination Watching Others Kill’, Vanessa Tothill notes the existence of the scapegoat mechanism, in which ritual forms of sacrifice “served to refocus a community’s shared existential anxieties about death onto the mortal body of another”. The anthropologist René Girard noted a subversive movement in the Bible away from human sacrifice through animal sacrifice to the ultimate sacrifice of God in the person of the crucified Jesus Christ. For those that follow, the sacrifice of Jesus is the sign that the need for the scapegoating of others has been rendered null and void. This understanding of violence and its subversion is summed up in Jesus’ words equating his crucifixion with the raising up of the bronze serpent that brought healing.

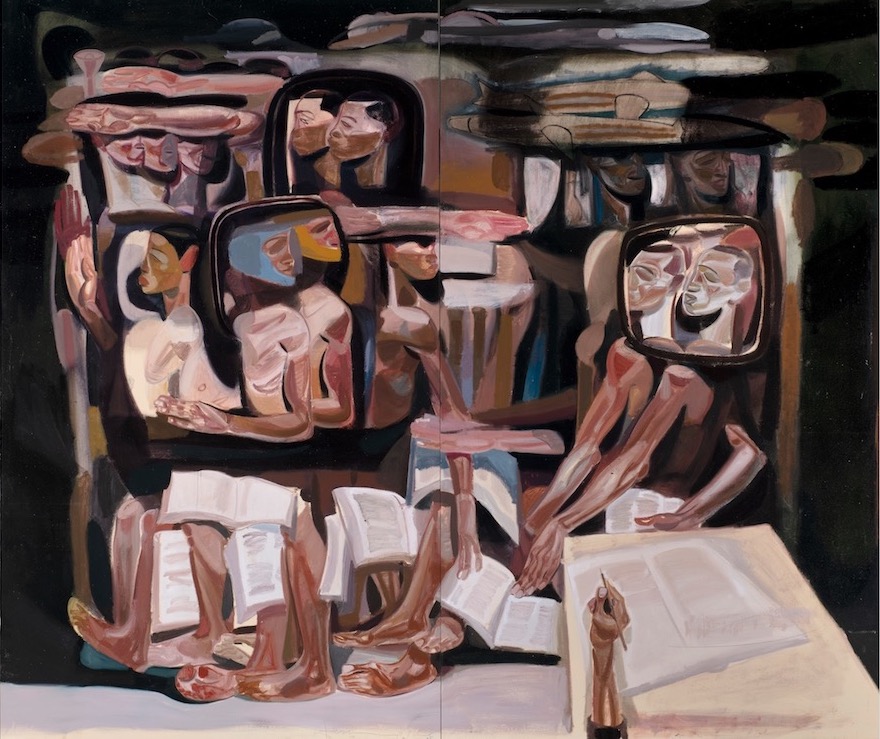

Tesfaye Urgessa, No country for young men, 31. Courtesy of Cheng-Lan Art Foundation and Saatchi Yates

Within these exhibitions, the rejection of violence and its reversal through resilience are primarily to be found in a series of images created by Urgessa, whose work combines the influence of Ethiopian icons with the techniques of modernism. Urgessa seeks to “represent the complexity of human existence without labels”. His figures embody “suffering and strength”: “I want my figures to stand with confidence, to present themselves without judgement and to radiate that they made it through something, but they’re still standing, they’ve healed and they carry their scars with dignity.”

Urgessa recognises that art can do this because “it fulfils something essential in how we express ourselves and connect with the world”. That is essentially the perception which forms the base for The Sainsbury Centre’s radical exhibition programme and makes Urgessa an ideal artist in residence. However, the image, par excellence, for ‘Can We Stop Killing Each Other?’ is perhaps to be found in the upcoming ‘Seeds of Hate and Hope’. Mona Hatoum’s ‘Hot Spot’ is a steel globe with its continents traced in red neon. In White Cube’s description of this work, we read that: “the work buzzes with an intense energy, bathing its surroundings in a luminescent red glow. Compelling and seemingly dangerous, Hot Spot suggests that it is not simply contested border zones that are political hot spots but an entire global situation: what Hatoum describes as a ‘world continually caught up in conflict and unrest’.”

As Cooper writes in the exhibition’s catalogue: “The power of art is that it can … allow us to look the reality of killing more closely in the eyes … The artists, curators and academics [involved in ‘Can We Stop Killing Each Other?’] populate a landscape of experiences, imaginings and realities that enable anyone to find their own answers to the question: ‘Can we stop killing each other?’”

‘Can We Stop Killing Each Other?’, The Sainsbury Centre:

‘Tiaki Ora ∞ Protecting Life: Anton Forde’, 2 August 2025 – 19 April 2026

‘Eyewitness’, 20 September 2025 – 15 February 2026

‘Roots of Resilience: Tesfaye Urgessa’, 20 September 2025 – 15 February 2026

‘The National Gallery Masterpiece Tour: Reflections on Peace’, 20 September 2025 – 11 January 2026

‘Seeds of Hate and Hope’, 28 November 2025 – 17 May 2026

Visit Here

Lead image: Tiaki Ora Protecting Life, Photo Kate Wolstenholme