On 7th October 1943, Charlotte Salomon was deported to Auschwitz. She was 26 years old and five months pregnant. She probably died the day she arrived, one of the estimated 1.1 million people who did not make it out of that concentration camp alive.

An exhibition of 236 of these gouaches is now on show at the Jewish Museum in Camden

It is possible we would never have heard about this young German Jewish woman from Berlin had it not been for the vast collection of paintings she did in the two years before her death. The work, a total of 1299 gouaches on paper, were brought to light at the end of the second world war.

An exhibition of 236 of these gouaches is now on show at the Jewish Museum in Camden, on loan from the Jewish Historical Museum in Amsterdam. The show is nothing short of extraordinary. Not only does it provide documentation of the horrors of Nazi Germany, both before and during the war, but in a very unique way tells the story of this woman’s own tragic journey.

In 1938, Salomon was 21 and a student at Berlin’s state academy of art, where she was one of just a few Jewish students. When the Nazis arrested her father, he arranged for her to join her grandparents in Villefranche, just outside Nice, however in 1940 her life was thrown into further turmoil when her grandmother committed suicide and she discovered that both her aunt and her mother had also committed suicide – her mother died when she was just eight years old.

A few months later, Salomon and her grandfather were sent to an internment camp. They were released five months later, but Salomon was so traumatised by everything she contemplated ending her own life. It was only when a doctor advised her to take up painting as a form of therapy that she embarked on “something insanely extraordinary”.

Desperate to understand what had happened to the three women in her family, Salomon created a play, not in the conventional sense, but one with painting at its core. Influenced by theatre, opera, cinema and art history, the play centred around her family, herself included, and spanned four decades, all reflecting true events as they happened. She called it Life? Or Theatre?

At the beginning of this exhibition, Salomon presents us with a prelude to her play, choosing the bleak suicide of her 18-year old aunt to open. This tragedy took place four years before Salomon was born, but eerily she depicts her aunt leaving her house, the grey-blue lake where she drowns herself, the report about her death, and the open coffin where she lies, her hands clasped and her youthful face surrounded by her long flowing dark hair.

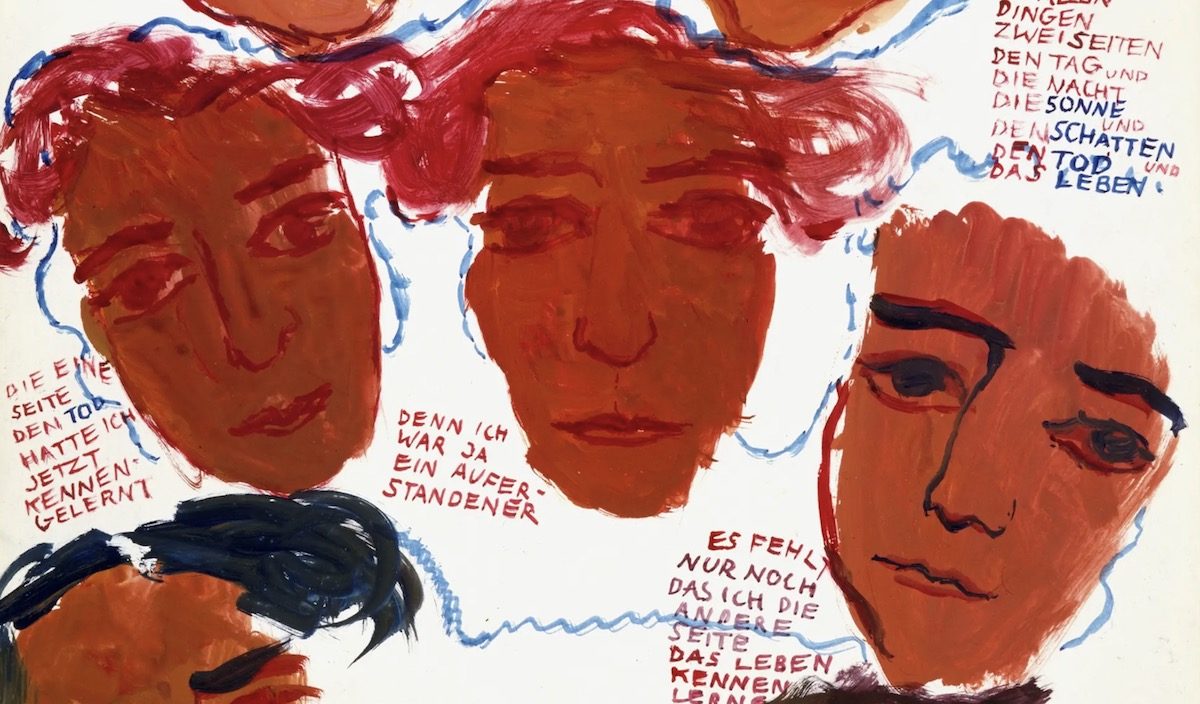

Using sheets of paper and gouache, Salomon switches between full-length portraits of her family to full-size headshots; fleeting sketches to tiny details; bright brushstrokes of blues yellows reds and greens to pools of darkness. Emotions are evoked on every page. She deploys strips of narrative, as if she were storyboarding a film, and divides and subdivides pages to illustrate houses interiors or a timeline of events.

The voices of all her main characters are brought to life with dialogue; sometimes just a single line, other times, a page of script. Text, large and small, interweaves many of the pages. She also lists the music she imagines playing in the background of a scene – a song, a melody, a classical movement. She taps into all our senses. The playwright and theatre director all rolled into one.

Salomon’s father was a surgeon and her mother was a nurse, and her prelude continues with the story about how they met on the front line during the first world war. In 1916, Salomon imagines the happy scenes of their wedding day – her mother’s white dress, her bouquet, the roses and candles at the banquet, the honeymoon. Delicate and beautifully evoked, the images are filled with the hope and promise of love and new beginnings.

She captures her own birth a year later: a baby girl, loved and adored; a basket, white sheets, a mother cradling her child, the pram; birthdays, toys, a snowman, a Christmas tree full of lights. She weaves together a rich tapestry of childhood memories and what she imagined might have happened.

But happiness gives way to despair as Salomon starts to confront the bleaker side to those early years: her mother’s fragility, the strange conversations, her bouts of depression and thoughts about being in heaven that ultimately lead her mother to jump to her death from a window. Salomon is told her mother has died of influenza.

And so Salomon’s journey begins: joyful, moving, confusing, painful, courageous, dark, and ultimately tragic. But it isn’t just a story about the women in her life. It is also about the men; not only her father, Albert, who remarries a celebrated classical singer, but also her stepmother’s new singing teacher, Alfred Wolfsohn, and the man who Salomon becomes infatuated with.

We know how significant this man is in her life because she introduces him to us in the opening pages of the main section of her play. She depicts him over and over again: standing, sitting, lying, thinking, talking; their secret meetings; their carefree memories of making love. Her obsession with him spills out onto the page.

One of the most striking pieces is a sequence of small vermillion headshots in which Salomon features him talking to her; his dark hair and good looks captured in a tilt of the head, a longing stare, a hidden smile as if she wants to describe every possible expression on his face. She adds quotes by him, such as: “Well, you do show a certain amount of courage. Perhaps you’re not nearly as shy as you make out, perhaps you’re quite a ‘dangerous’ girl!”

What is fascinating is that all his words are in her head, but as the quote above suggests, you wonder whether she was confused or frustrated by what he really meant. Is he criticising her? Flirting with her? Praising her? Mocking her? Teasing her? What is very clear, however, is that he was a huge influence on her and her work till the end.

Running through Salomon’s paintings is a sense of urgency as if she knew she would have to stop at any minute. And, of course, the rise of Nazism is never far from the pages: the Gestapo, Nazi propaganda, the “night of broken glass”, the German occupation of France, the crammed railway carriages deporting Jewish people to concentration camps…

Salomon’s play has an epilogue that covers the period 1939 to 1942 and at the end of it, she states: “I became my mother, my grandmother, in fact, I was all the characters in my play. I learned to travel all their paths and become all of them.” Who could not agree?

Salomon’s grandfather was the last member of her family to be with her. However, in one final addition to her work, she adds a letter in which she seems to confess to giving her grandfather a fatal overdose in the spring of 1943. This letter was not made public until 2015. Many questions still hang over the nature of their relationship.

Salomon only remained hidden in the south of France as long as she did because of the patronage of an American woman called Ottilie Moore. In the summer of 1943, Salomon even gets one last grasp at happiness when she marries an Austrian emigrant called Alexander Nagler. It is the last as a few months later they are both arrested and deported to Auschwitz.

Her art is kept safe by a trusted village doctor in Villefranche, but it is addressed to Ottilie Moore, who returns to France in 1946. She, in turn, gives all the work to Salomon’s father and stepmother, who both survive.

One small irony in Salomon’s story is that when she was at the Berlin art academy, she specialised in illustrating German fairytales. Her own life was anything but a fairytale, but the theme of many of these fairytales was the ability to triumph over difficulty, and in her art, if not her short Life, Salomon did just that.

Charlotte Salomon: Life? Or Theatre? Is at the Jewish Museum, Raymond Burton House, 129-131 Albert Street, London NW1, until March 1, 2020. There will be a series of talks at the Museum about the exhibition, including one on January 23 to coincide with Holocaust Memorial Day, from 6.30-8 pm. See the website, jewishmuseum.org, for full details; 020 72847384.