I have personal reasons to be interested in this book – Company Curiosities, by Arthur Macgregor. A direct ancestor of mine, not however mentioned in the text, was Chairman of the British East India Company in some of its glory days at the end of the 18th century. He survived imprisonment in the Black Hole of Calcutta and later served under Clive at the Battle of Plassey in June 1757. The EIC’s decisive victory there over the forces of the Nawab of Bengal and his French allies made the Company the ruling power in India until 1813. It did not lose all traces of this role until the so-called Indian Mutiny of 1857.

What fascinated was not Indian art as such, but the subcontinent’s wealth in new manifestations of nature – ELS

The Company Curiosities dust-jacket, illustrated here, carries a picture of the famous automaton called Tippoo’s Tiger, which shows an almost life-sized European victim, probably a civilian rather than a soldier, being mauled by the beast. The tiger was emblematic of Tipu Sultan, the ruler of Mysore, who had the object made. Tipu, supported by the French, was in frequent conflict with the British. He was killed in 1799 in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War, when defending Siriangapatna, and his capital was thoroughly sacked. One of the trophies taken from his palace, and sent to the UK, was this item, a large-scale political toy. Its meaning since then has changed several times. Not only quite drastically since it was made. But additionally, with the recent shift of attitudes towards the history of colonialism. Currently one awaits demands either for its return to India where it was produced (maybe complicated by the fact that Tipu was a Muslim, and not too nice to either Christians or Hindus). Or simply that the Victorian & Albert Museum, where it now resides as a hugely popular exhibit, should have it put away because it offends the growing tribe of snowflakes by its brutality.

What fascinated me about the book itself is how thoroughly it illuminates the clash of cultures between the British, who fleetingly ruled the sub-continent, and who strove to do good in it, as well as profiting from opportunities to make both themselves and the distant country they came from wealthy, and the culturally intractable environment within which they resided. What fascinated these temporary rulers, was not Indian art as such, but the subcontinent’s wealth in new manifestations of nature. For manifestations of Indian art, as we know it today, they had almost no respect. What interested them in this category, if at all, was the legacy of remote ages, such as Buddhist murals in the caves at Ajanta, made between the 2nd century BCE and the 5th century CE. But they knew very little about them.

The first half of Company Curiosities is full of illustrations of the birds, beasts and plants of the India that surrounded, one might even say engulfed, these privileged temporary rulers. Some were made by the British themselves, quite often by women, since men had better things to do. Others by native Indian artists whom the colonial rulers employed. These coloured drawings by local painters were what we now call Company School’ – adjusted to accord with the wishes and tastes of the European enlightenment. Though there are occasional images in which related species seem to have been confused, the underlying desire was to have accurate portrayals of things that existed – reflections of detached curiosity. If you couldn’t make the image yourself, you hired a ‘native’ who could.

There was also a wish to explore Indian crafts, notably the production of textiles, which were sometimes seen as rivals to European products in the same category. In the production of furniture by local makers based on European models, a touch of exoticism, in carved details or inlays, seemed an amusing local touch.

Where architecture was concerned, most of the nabobs who returned to a prosperous retirement in Britain preferred grand houses in the prevailing Palladian style. There are just one or two great country houses, built by EIC owners, that show marked influence from Indian architecture. The most conspicuous example is Sezincote in Gloucestershire, built in 1794 by Colonel John Cockerell, once Surveyor-General to the EIC. He intended at first to create a replica of the Taj Mahal, but ‘a committee of taste’, among them the painter Thomas Daniell, who had travelled a worked in India, talked him out of it.

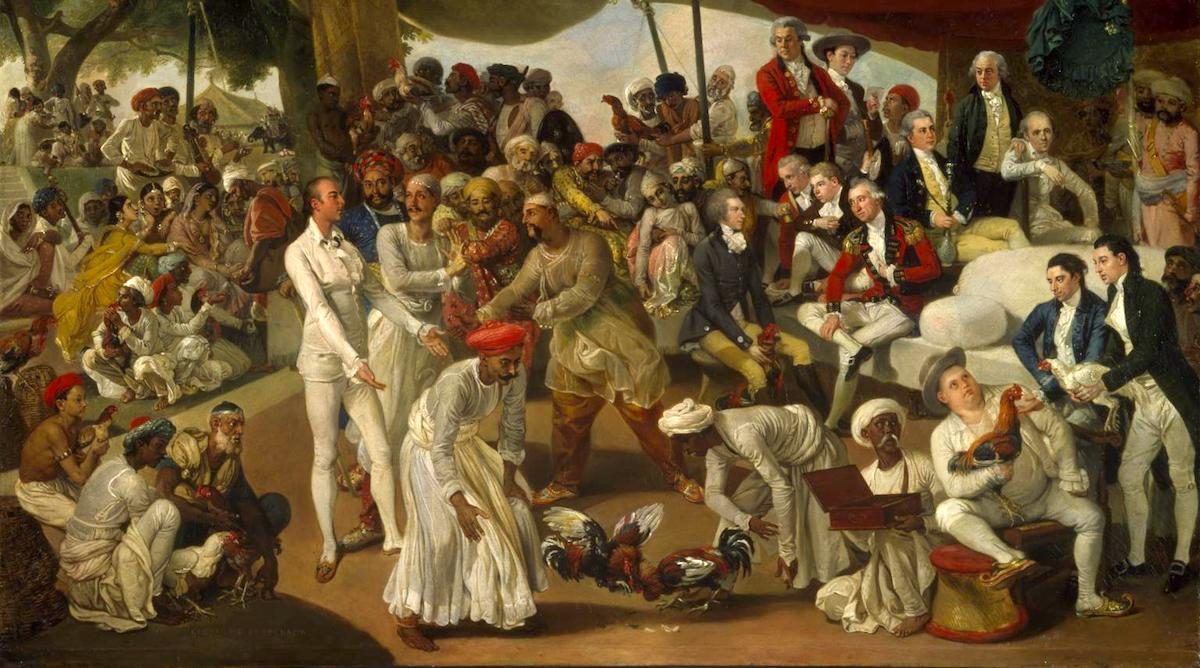

Daniell was one of quite a several British or British-affiliated painters who made views, portraits and even genre paintings in India. Perhaps the most famous example is Zoffany’s Colonel Mordaunt’s Cock Match (1784-6). Made in Lucknow, long before the city became infamous through the Lucknow Massacre, this shows the two ruling classes, British and Indian, mingling together. The Nawab of Lucknow, Asaf ud-Daula, then ruler of the city, stands at the centre. Colonel Mordaunt, to the left, in European dress, was the commander of his bodyguard. The painting, when completed, was bought by Warren Hastings, head of the Supreme Council of Bengal and first de facto Governor-General of India. He was Mordaunt’s previous employer. He later hung the work in his English mansion at Dalesford. That was as far as cultural integration went.

Though European artists sometimes made state portraits of Indian rulers, the two cultures remained quite separate.

Words: Edward Lucie-Smith © Artlyst 2019

Company Curiosities Nature, Culture and the East India Company, 1600–1874 Arthur MacGregor ISBN: 9781789140033

Buy Company Curiosities Here