Contemplating the Spiritual in Contemporary Art a new exhibition at Rosenfeld Porcini is proof, if proof is needed, that there is no shortage of artists exploring, as Erika Doss described them, ‘the intersections of iconography, religious orthodoxy, and issues of faith’. Doss’ claim was that ‘issues of faith and spirituality’ have been ‘very much a part of modern art … as artists of diverse styles and inclinations repeatedly turned to the subjects of religious belief and piety.’

This show has been carefully crafted through a depth of understanding of artistic motivations

Rosenfeld Porcini is a gallery that has been unafraid to show work inspired by spirituality, as evidenced by the work of Emmanuel Barcilon and Francisco de Corcuera, among others. This, however, is their first show dedicated to the contemplation of the spiritual.

It seems probable that Spirituality in Contemporary Art — The Idea of the Numinous by Jungu Yoon was a source of inspiration as, in his book, Yoon opens up the discourse between Eastern and Western art while exploring the use and misuse of spirituality in contemporary aesthetics. Similarly, ‘Contemplating the Spiritual in Contemporary Art’ was born out of a wish to look at the distinction between Western and Oriental approaches to spirituality and what it can tell us about the different ways we try to find meaning in our lives.

Yoon essentially suggested that Western art emphasises the existent over the non-existent, while, in the East, ‘Chinese painters became so aware of the significance of the non-existent that the voids in artwork were considered to convey more meaning than the solid areas.’ Such ideas are explored here through an exhibition divided into three separate sections. The first room examines responses to the stories in the Old and New Testaments and their roots in the human drama. The second features artists who use light rather than figuration to display the ‘divine’, while the third focuses on artists working within pure abstraction to convey a spiritual significance.

Benitha Perciyal’s art finds its foundation in her strong Christian faith, both in iconography and materials. Her materials, such as myrrh, frankincense, cloves, cinnamon, lemongrass, bark and cedar wood, are all either related to the specific story of Christ or timeless, natural elements that would have existed at the same time that Christ was alive. Her incense sculpture Dark am I, yet lovely don’t stare at me, because I am dark is an evocative tableau of fractured beings attesting to the mysterious and miraculous nature of Christ-like attention. The Romanian artist, Teodora Axente’s collages, evoke the duality of spiritual and material and reference the human desire to reshape oneself to reconcile past, present and the future. In ‘Pieta’ and ‘Vertical’, she uses collage to find new ways to see and show the traditional images of the dead and resurrected Christ.

As a child in Guatemala, Luiz González Palma was overwhelmed by church sculptures and Baroque images. The emotional intensity captured there is reproduced in his own creations. With La Luz de la Mente (The Light of the Mind), González Palma has taken some of the most famous ‘Crucifixion’ scenes from Old Master paintings by Velázquez, Rubens, El Greco, and others and recreated the loincloths of Jesus Christ as depicted in these paintings as an installation which he has photographed. This perizoma becomes equivalents for the crucifixion itself. By spotlighting the mantle of modesty in the most essential European paintings of the crucifixion, González Palma makes poignant connections with the sacred experience of isolation and emptiness.

Similarly, Mark Alexander’s Red Mannheim turns an image of the Mannheim altarpiece into a crucifixion equivalent by echoing its story ‘of loss, transposition of meaning and woundedness’. Its deep blood-red tones evoke ‘birth, life and healing as urgently as bloodshed or burning’ and speak to the ‘scarred quality’, ‘so central to our emotional and spiritual lives’.

It is worth pausing at this point to reflect on the reasons why artists can adapt, alter and constructively play with Christian iconography in this way. For purposes that were intimately related to the incarnation Christianity engaged with the visual arts to an extent and depth that was less so for the other Abrahamic faiths, where abstraction and calligraphy became the primary forms for approaching the divine. It is the Christian embrace of the visual – the figurative, abstract and conceptual – that enables artists today to draw on and transpose aspects of the visual heritage of Christianity in ways which are not available to the same extent through the visual legacy of the other Abrahamic faiths. The Church regularly finds this artistic engagement with its legacy challenging, yet, where embraced, the theological imagination of the Church is creatively stretched.

Moving into rooms and works based on light and abstraction, we encounter Roberto Almagno, who wants to make ‘works that express the prayer and sacrifice’ of humanity ‘when faced with time and infinite space’. His search involves a strong element of mysticism making drawings with ash and soot, where ashes are seen as ‘the essence of all forms, continually changing, precarious and transitory’. His shapes appear as if emerging from the darkness, while the slither of light surrounding them suggests the infinite space of the universe. Almagno’s Ombre 2001 is neatly countered by Hiroshi Sugimoto’s photograph of ‘Notre Dame de Haut’, the Church built by Le Corbusier in France, suffused by light.

Lu Chao works in the gap between what we do and what we do not know. This space is what shapes the beauty and excitements of life. His oil paintings make bold and adventurous use of black and white, a tribute to the economy of means embodied by traditional Chinese black ink painting. Anonymous bodies in miniature are perilously suspended in space attempting to negotiate the cosmos or gathered around a vast God-like head or contemplating a monumental, mysterious, black sphere in a Cathedral. ‘We find it difficult to understand our own persona truly, and we find it even more exhausting to comprehend the world around us’, he suggests.

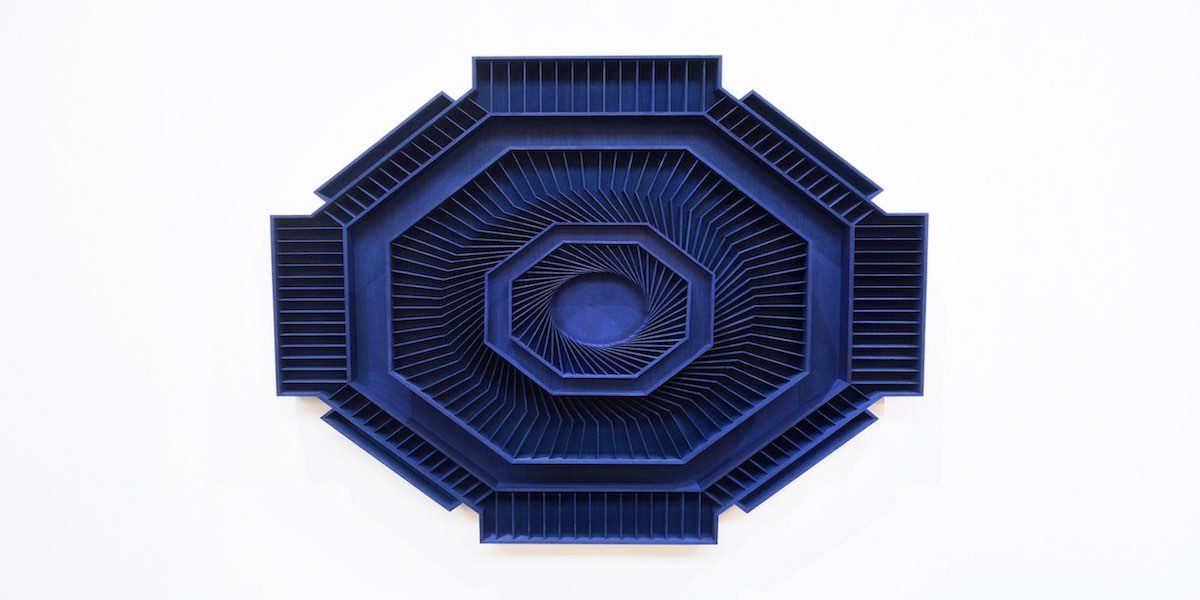

The grandson of a minister, Levi Van Veluw has been fascinated with the Church and its rituals since his youth. Recognising that people practice their faith in places of worship, using sacred objects and performing holy rituals, Van Veluw creates spaces of ritual stripped of specific religious references to explore the extent to which a sense of holiness and connection with the beyond remains. His wall sculpture Sanctum conjures up images of Romanic churches while beguiling us into its mysterious interior where infinity seems to recede continually.

Shen Chen painstakingly creates as if in a meditative trance. Chen has described his intimate process of ‘stroke-laying’ as entering a void and dismissing all thinking. ‘Such reflection of the inner spirit,’ he suggests, ‘is a poem of a stream of consciousness’ wherein the ‘strokes as artworks are but the remainder of the process and the trace of time and spirit.’ Similarly, Riccardo Guarneri’s Zen-like lyricism dissolves the boundaries of his pastel colours, pointing to a place where time is imperceptibly stretched outwards.

The final piece in the show is a video by the Korean artist Bongsu Park which focuses on a vision of creation. A dancer is curled in a foetal position under a partially transparent sheet similar to a cocoon. As she slowly emerges into life and movement, the act of birth becomes a transcendent metaphor for the act of creation itself.

This show has been carefully crafted through a depth of understanding of artistic motivations and a breadth of view across the contemporary art scene. It has been intelligently gathered and curated to evoke ideas around infinity, time, space and the eternal question of why we are on this planet and how are we to make sense of our being here. As such, it is one of the strongest and most sensitive surveys I have yet seen of contemporary art which engages spirituality in its many forms.

‘Contemplating the Spiritual in Contemporary Art’, 7 June – 13 July 2019, Rosenfeld Porcini

Notes: Coming Home! Self-Taught Artists, the Bible, and the American South, ed. Carol Crown, University Press of Mississippi, 2004.

Mark Alexander’s ‘Red Mannheim’ at St Paul’s Cathedral

Roberto Almagno – The Perfection of Form, Roberto Almagno and Rosenfeld Porcini, 2012.