Exhibitions in major galleries are usually planned years ahead. So it is the Royal Academy’s good fortune that their two excellent shows Revolution: Russian Art 1917-32* and American After the Fall: Painting in the 1930s, should be so in tune with the current political zeitgeist, which could not conceivably have been guessed at the time of scheduling.

After the Fall covers the period from the late 1920s up to the US’s entry into World War II. The ‘fall’ of the title refers to the stock market crash of October 1929 and embodies not just a vision of economic crisis but, also, a loss of innocence and the collapse of the American dream. After the Wall Street crash disillusionment set in. And, with it, a desire to reassess democracy and question what it meant to be American, as Fascism took hold in Europe, and Communism in the Soviet Union. The 1930s was a critical decade. A time when the character of America was changing. A period marked by mass migration from the countryside to the cities. Millions were forced, as John Steinbeck in his novel, Grapes of Wrath, so graphically evoked, to flee the parched and devastated dust bowl areas like Oklahoma, as debt threatened the viability of small farms and homesteads.

American is not homogeneous and never has been. It is a nation constantly in search

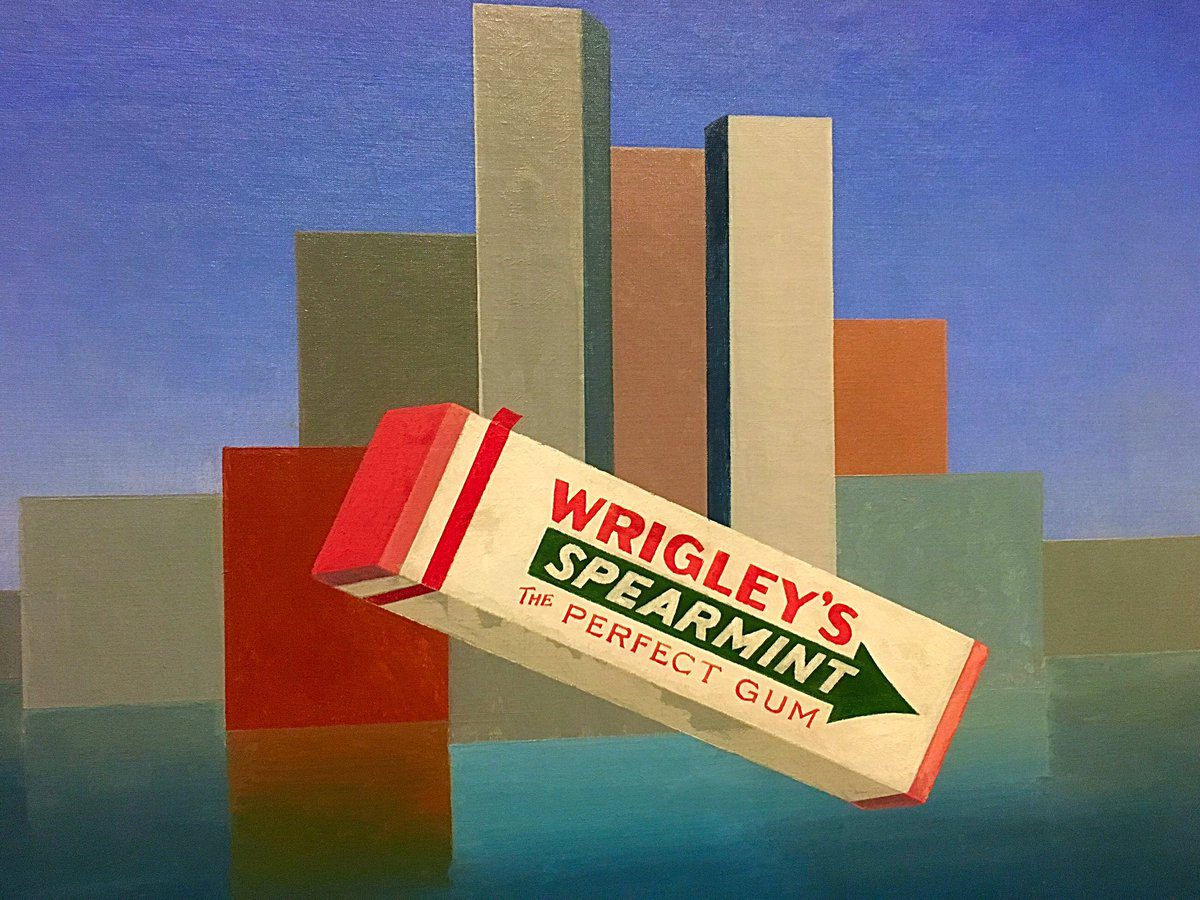

The exhibition opens with Charles Green Shaw’s iconic painting Wrigley’s 1937, in which a packet of spearmint gum floats against a background of tall rectangular shapes, reminiscent of the New York skyline. It is an iconic image. One that suggests a homogenous America: consumerist, capitalist, confident, primarily urban and modern. But the lesson of this exhibition, and its relevance to the current political climate, is that American is not homogeneous and never has been. It is a nation constantly in search – like Pirandello’s six characters – not of an author, but of an identity. Even the Midwest, which harboured the myth of the pioneer farmer-settler from the first days of the republic was, in fact, a pluralist society made up of many ethnic groups and cultural identities that included Irish, Germans, Swedes and African Americans. And that pastoral identity then, just as now, was diametrically opposed to the other America exemplified by the metropolitan seaboard cities such as New York, with their taste for innovation, intellectualism and inclusivity.

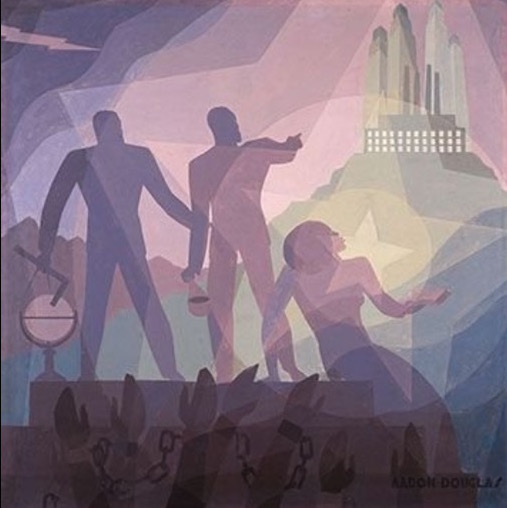

This cultural duality is nowhere better illustrated than in two works, Aaron Douglas’s 1936 modernist painting, Aspiration, in which the silhouettes of two black men and a young woman look towards a city of skyscrapers set on a hill, like some golden Jerusalem. One of the men holds a set square and a draftsman’s compass. The group’s stance is confident and optimistic as they gaze into the brightly lit future. Below them, reaching from the subterranean darkness of the lower picture space, are the chained hands of anonymous black slaves. The implication, here, is that the past may have been tragic but that with talent and hard work a shimmering future awaits. This image stands in stark contrast to Joe Jones 1933 American Justice, in which a group of hooded Klansmen have just set fire to a homestead where, in the foreground, a traumatised, half-naked black woman lies beneath a noose swinging from a tree in a shocking visual illustration of Billy Holiday’s song Black Fruit. These works illustrate the two strands of 30s America: as the land of freedom and opportunity for all, and a nation of conservative values espoused by those who saw themselves as connected to the original settlers.

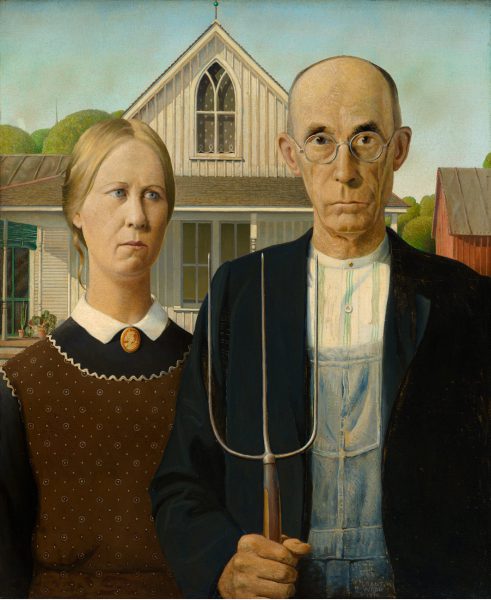

The strong narrative vision of Grant Wood’s painting, Daughters of the Revolution, 1932, places three steely-haired, tight lipped, bespectacled ladies – full of zealous righteousness and a sense of entitlement – in front of a copy of the 1851 triumphalist painting Washington Crossing the Delaware by the German-American Emanuel Leutze. While the impetus for the show’s most famous painting, American Gothic, came from a visit Grant made to the small town of Eldon in his native Iowa. There he spotted a little wooden farmhouse made in a the Carpenter Gothic style and wrote: “I imagined American Gothic people with their faces stretched out long to go with this American Gothic house”. Using his sister and his dentist as models, he dressed them up as a farmer and his daughter, like “tintypes from my old family album”, the formality of their pose inspired by the Flemish Renaissance art he had discovered on his travels in Europe during the 1920s. Many read American Gothic as a satirical comment on Midwestern values. But it is more likely that Wood intended it to be positive; a mirror reflecting the unchanging values of rural life in a period of dislocation and disillusionment. Within this world of harvest and handicrafts, white churches, red barns and Shaker style interiors, the figures in their old style dress, with their three tine pitch-fork, cameo and steel rimmed spectacles represent hard-core survivors. In his 1935 essay, Revolt against the City, Grant wrote that the Midwest “stood as the great conservative section of the country”; a symbol of unchanging America against the eclecticism of the cities. A view that remains just as true today among most of Trump’s supporters.

This dichotomy between urban and rural, avant-garde and conservative, abstract and figurative is further played out in the style and subject matter of the paintings on display and in the diverse ways artists responded to the promise and disillusionment of the American dream. To express the mood of these rapidly changing times and forge a uniquely American (as opposed to European) language, many turned away from the romanticised landscape of Grant and idealised scenes such a Doris Lee’s bustling Thanksgiving preparations in a Midwestern kitchen, to urban subjects. Charles Sheeler’s 1930 hyperreal vision of Ford Motor Company’s River Rouge Plant illustrates the hope invested for the future in industry, and Charles Demuth’s 1931 …And the Home of the Brave attests to the influence of European Cubism and Modernism. While the vibrant life of urban blacks is graphically presented in William H. Johnson’s 1939 Street Life, Harlem.

As in America today, fears of social collapse were fired up during the Depression by the media. The kidnapping of the aviator (and Fascist supporter) Charles Lindbergh’s young son, and the many gangland assassinations and lynchings were presented as evidence of a dystopian society in steep decline. Urban life, though, was, like much else, not homogenous. Paul Dadmus’s 1934 The Fleet’s In, demonstrates something of its liberating release from the strictures of life on the prairies. With its knot of smoking, drinking sailors, some in buttock-clenching trousers that pin-point to them being gay, others flirting with girls of easy virtue, it dared to show a bawdy scene of sailors hanging out in New York’s Riverside Park. As a result it was confiscated by Franklin Roosevelt in order to uphold – on the brink of war – the navy’s reputation.

By the 1930s dance marathons had become a popular part of the ‘culture of poverty’. These commercially driven endurance tests, which might last more than eight hours in the hope of a monetary prize, were graphically illustrated in the 1969 film, directed by Sydney Pollack, They Shoot Horses Don’t They?, based on the 1935 novel of the same name, by Horace McCoy. In his disturbing 1939 painting, Dance Marathon, Philip Evergood echoes the decadent glamour of the Weimar Republic mythologised, in Germany, by Max Beckmann, as well as referencing the exaggerated figures of Toulouse-Lautrec’s demi-monde.

This artistic sparring between differing visions and styles continued to be played out between those who wanted an American art rooted in realism and those who were attracted to abstraction as a universal language that pushed beyond the boundaries of class and nationalism. European movements such as Surrealism also caste their influence on the Magical Realism of the likes of O. Louis Guglielmi and Morris Kantor. Generally uplifting subjects, painted in a realistic style, were preferred by the support programmes of Roosevelt’s New Deal, administered through the Public Works Art Project. Though not all rural visions were conservative and sentimental. New Mexico attracted modernists such as Georgia O’Keeffe who used the language of landscape, as opposed to that of farming, to create quasi-abstract paintings that explored the atavistic character of the natural environment.

The 1930s began the process of defining American culture; asking what that culture was, and who it was for. Was America still the same place envisaged by the Founding Fathers? What mattered now? History and myth or modernity and progress? Industrialisation or the farm? A monoglot Anglo-Saxon culture or a multi-ethnic one? Perhaps the lesson for our contemporary world is that nostalgia – then as now – is usually a form of deceit. The much vaunted myths of rural self-reliance failed to adapt to the new interconnected global world. People did not, as Grant predicted, “revolt against the city” and return in their droves to their little houses on the prairies. By the 1940s Edward Hopper and Jackson Pollock exemplified the two poles of American painting and the tensions between the local and the global. For many, American art would become defined by the heroism of Abstract Expressionism and, later, Pop art, with its elite avant-garde of urban intellectuals and hipsters. Post-war America found that it had less of an appetite to look back to its pioneer roots as it became increasingly involved economically and militarily in the global web of events. Yet the question of what constitutes America and who owns its cultural and political soul has not gone away but resurfaced with Trump’s victory. It will be interesting to see if, during this 21st century crisis, a new art emerges that reflects something of this ongoing schism in the American psyche.

Words: Sue Hubbard Photos Courtesy Royal Academy London Main Photo: Charles Green Shaw Wrigley’s 1937

America After the Fall: Painting in the 1930s The Royal Academy until 4th June 2017

Sue Hubbard is a freelance art critic, award-winning poet and novelist. Her third novel, Rainsongs, is due from Cinnamon Press this autumn. www.suehubbard.com