In 1998 the first sales of the Dora Maar collection were put on sale in Paris. They revealed a life dedicated to photography, painting and poetry, executed in the city’s avant-garde milieu of the 1930s.

Like many female artists, she is best known for her biography as helpmeet to a more famous male artist – SH

Maar’s friends included the poet Paul Eluard and the painter Balthus. At the time, the international art market was buzzing with excitement about the Picassos up for auction that season. In comparison, Maar’s work met with relative indifference. For most, her chief claim to fame was – with her dramatic dark hair and smouldering eyes – as a surrealist icon and the ‘muse’ to Picasso’s eternally lachrymose ‘weeping woman’. Like many female artists, she is best known for her biography as helpmeet to a more famous male artist and for her psychological and emotional difficulties. As a result, her artistic output has been overshadowed by Picasso’s giant oeuvre and personality.

This autumn Tate Modern redresses this art-historical redaction with the first UK retrospective of Maar’s surreal photographs, provocative photomontages, and paintings. Her incisive eye spanned six-decades of commercial commissions, social documentary and street photography, moving from Picasso influenced paintings through to abstraction.

Born Henriette Théodora Markovitch in 1907, she preferred to be called Dora. – Her father was an architect and her mother ran a fashion boutique. Raised between Argentina and Paris she had a cosmopolitan childhood, attending one of Paris’s most progressive art schools. In her 20s she turned to commercial photography, as it gave greater security than painting, sharing a darkroom with the photographer Brassai. Young and ambitious, her first photographic commission in 1931 was for a book by the art historian Germain Bazin, followed by publications in a range of magazines from the literary to the commercial. In 1932 she set up a studio with the respected set designer Pierre Kéfer, under the name Kéfer-Dora Maar.

Female photographers were rare between the wars. Maar was described as a ‘brunette huntress of images’. Such language classified women photographers as explorers traversing the boundaries of a society where their autonomy was still largely restricted. Beginning to compete for jobs in fashion, traditionally the domain of men, they were also breaking taboos to work in nude photography and erotica. When Maar entered the workplace, photography was replacing hand drawings in advertisements to promote shampoo and cosmetics such as Ambre Solaire, used for the newly fashionable pastime of sunbathing,

In these interwar years, the idea of the liberated modern women was promoted by advertisers and magazine editors. Maar liked to subvert the idea of a woman’s conventional role by slipping in imagery that was considered daringly modern, such as women wearing trousers or smoking. In two photographs taken for L’Art vivant, she uses photomontage and the insertion of a female model to destabilise the scale of the object advertised – a car – that most modern women could neither afford to own nor were able to drive. Her pictures were created by combining layered negatives to produce a single image that, according to the critic, Rosalind Krauss, ‘ensures that a photograph will be seen as surrealist…and always constructed’. Shots, such as those of Jane Loris, (Prévert) in a bathing suit doing callisthenics, or the erotic experimentations with the model Assia Granatouroff – the model who exemplified the 1930s nude – highlighted the growing interest in health and fitness that had been gaining popularity since the First World War.

The 1930s in Europe saw the worst economic depression in modern times. It was in this climate that photographers used their new art form to document the social deprivation they were witnessing. Some of Maar’s most affecting images were taken in Barcelona and London. Committed to left-wing politics, she not only showed compassion for a lot of those she photographed but had a keen eye for irony. This can be seen in her image, a city businessman down on his luck and looking for work while selling matches. Dressed fastidiously in cravat and pince-nez, holding a bowler hat, he might be off to his Mayfair club.

It was in the winter of 1935-6 that Dora Maar met Pablo Picasso who was emerging from the breakdown of his relationship with Marie-Thérèse Walter, with whom he had a child. He and Maar collaborated together in the darkroom, she teaching him specialised photographic techniques that enabled him to explore the possibilities of cliché verre, (painting combined with photography), while he encouraged her to paint. Her painting, The Conversation 1937, in brown and rust tones, addresses her relationship with Picasso’s former lover. The two women sit at a table. The blonde Marie-Thérèse, with whom Picasso remained close, facing the viewer, the brunette Dora Maar her back turned to them.

After learning of the attack on Guernica, Picasso began making preparatory sketches for his most famous painting, which Maar documented as a commission for Cahiers d’art. In contrast to her photography, her painting is much less known. In the dark war years, during which her father disappeared to Argentina, her mother died and her relationship with Picasso began to break down, she returned to painting, creating melancholy landscapes and still lives of jugs and pears, painted in grey and brown tones that mirrored the dreariness of her solitary life under the Occupation.

In 1945 Maar began to divide her time between Paris and a new home in the South of France. This saw a period of looser mark making and gestural impressions of nature made in ink, oil and watercolour. Though photography still interested her, the social documentation of the world outside her studio did not. She became more involved in seeing what she could create in the darkroom by laying household objects on photo-sensitive paper or tracing light across the surface. These works were only revealed after her death. In 1946, on the verge of making her name, she had stopped exhibiting. The psychic distress following her breakup with Picasso led to a decade long silence when she did not show her work, though she did continue to create in the privacy of her studio.

And how should we rate her now? While her painting is always in danger of being compared with the great talent of her lover Picasso, it is her witty, stylish and compassionate photographs that caught the zeitgeist of the times in which she lived, that are likely to be her true legacy.

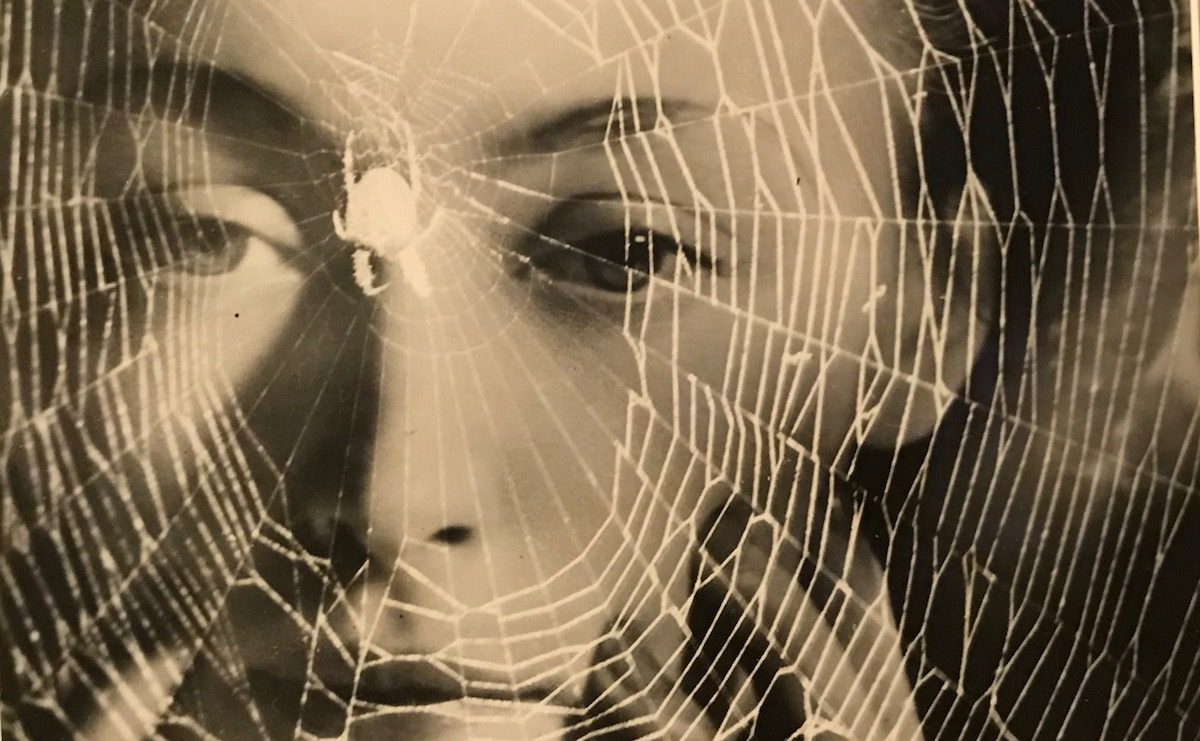

Top Photo Dora Maar (detail) “The years lie in wait for you” (c. 1935). (Portrait of Nusch Eluard). Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

Words: Sue Hubbard © Artlyst 2019 Photos Courtesy Tate Modern

Sue Hubbard latest novel Rainsongs can be bought here: