Books! Thousands of books! Written by hundreds of authors from scores of countries, and countries not their own, forced by circumstance, persecution, and censorship to move and sometimes even to write in languages not their own. Books written in exile by the exiled. It is this phenomenon, the triumph of the human spirit in dire circumstances, that is the focus of a gesamtkunstwerk, a complete work of art, by Edmund de Waal which may be viewed at the British Museum when it reopens, and also investigated online as of now. The various sites have a wealth of information: de Waal’s own impassioned talks, views of the library’s previous iterations on its journey over the past many months, and listings of the books that are included.

Library of exile is the first piece by the artist to combine words, real objects that have had a life outside the current display – the books – and art

Museums themselves are places of exile; almost nothing that a museum cares for and exhibits, its wealth of objects, its reason for being, the collections vast and small was at first meant to be there. Yes, they may contain collections which were purposefully put together or commissioned by an original owner, perhaps even with the thought eventually of public show. But the vast majority – from churches, and temples, from tombs and funerary monuments, from rituals of countless societies, had a life in the world that did not envision being on public view out of time and context. Now they are part of the three-dimensional library of history, of material culture, that is a museum on whatever scale. Thus it is deeply appropriate that Edmund de Waal’s library of exile is currently located indeed in the end room of the great Edward VII Library in the British Museum, and that Edmund himself is both an artist and a writer.

The art came first as he was wholly absorbed, after a degree in English, in becoming a potter, an activity that had enthralled him from an early age. And his own family history is one of displacement, exile, new beginnings. The history goes back to Odessa, then Paris and Vienna, to great wealth and then displacement, migration, exile and new lives in exile from their specific personal cultural histories. This is what Edmund was to write about. It was getting to know his great-uncle Ignace Ephrussi – Iggie – in Japan who left him the extraordinary collection of netsuke which was to inspire de Waal’s family history of that migration and exile, The Hare with Amber Eyes (2010). Presciently, this family memoir has been translated into more than twenty languages – German and Hebrew, Spanish and Turkish, Estonian and Romanian, Finnish and Japanese, Chinese and Hungarian among them.

But he has not only explored the personal history of his immediate ancestors. Five years later he published The White Road (2015) the cultural ramifications – and travels – of the material with which he has had such a creative relationship, the material of his art, porcelain.

Edmund de Waal’s first environmental piece was a Wunderkammer, a three-walled room installed in the Geffrye Museum, 2002, with innumerable porcelain cylinders on shelving reaching to the top and, it felt, even beyond. Signs and Wonders, 2009, is an enormous circle of porcelain vessels- not only cylinders but plates and other forms reminiscent of the way porcelain is not only the most beautiful magical material but also has been captured for the quotidian. It is permanently installed in a vast circle in the circular dome of the Victoria and Albert Museum. An indication of where to look up and see Signs and Wonders when in the huge main entrance hall of the museum is embedded in the lobby floor. One of the sadly unvisited collections indeed is the world-class ceramics collection on the sixth floor of the V& A. Included are Ceramics from countries across the millennia, complete even with a working studio. It is not well signposted – visitors have to find out how to get to it – lifts, staircases and so on. However, they will be rewarded with an astounding journey through the history of an art form which is not only the oldest three-dimensional art form but also one intertwined with daily life: something that unifies all cultures. It is an art for the connoisseur and the art of the quotidian.

De Waal has a deliberately recognisable vocabulary of shapes archetypes almost of age-old domesticities – vessels, cylinders, plates, containers, jars, receptacles – but is able to create an almost endless series of themes and variations. He produces groups, almost a library, or series, sometimes just one or two, sometimes hundreds, even crowds, each subtly individual. Their glazes offer an almost unimaginable variety of whites, occasionally sharpened by reds and golds – rather as a painter uses brushstrokes, to make something far more than an individual form or gesture. The endless play of minuscule variety in glaze and form sharpens awareness.

De Waal also almost invariably titles his work. The four vitrines installed in the porcelain pavilion are indeed Psalms 1 – 4.

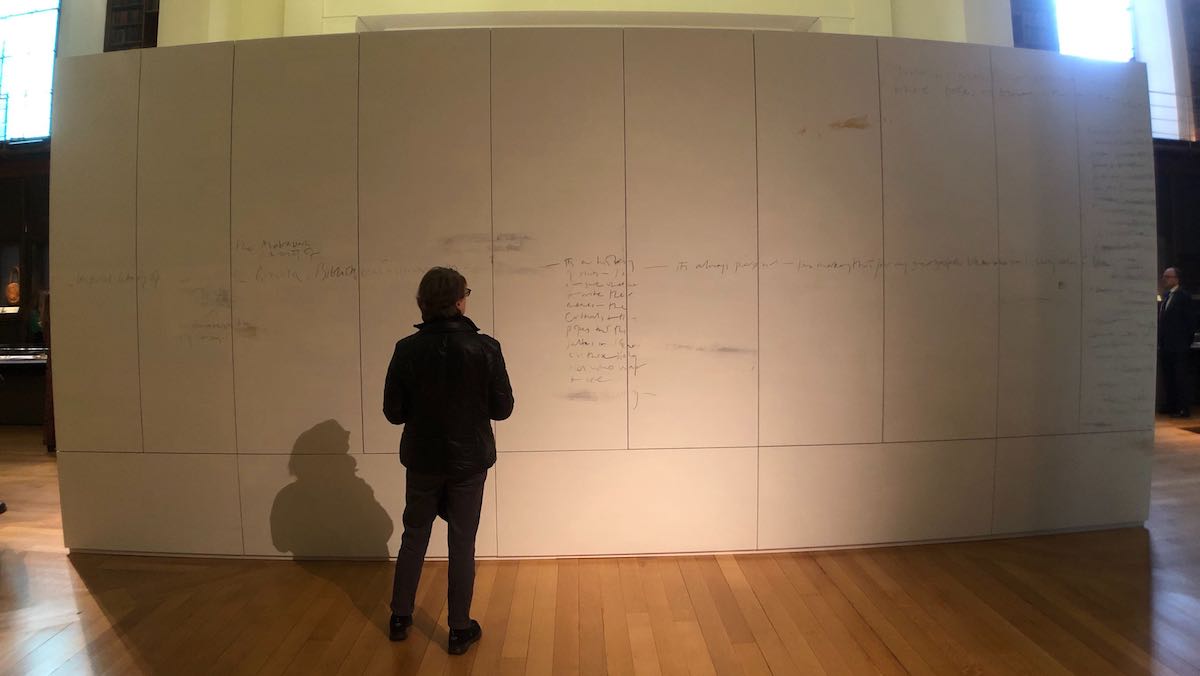

Library of exile is the first piece by the artist to combine words, real objects that have had a life outside the current display – the books – and art. Plus, the library of exile has had a significant itinerary from the summer of 2019, always in an emotive pre-existing setting and environment. It has travelled: opening in the Venetian ghetto, where Jews were forced in the early 16th century to live in a small section of the most international city of the day.

The library went on to the Japanese Palace in Dresden. Here too, of course, there were layers of history. A prominent Dresden Jewish family had made the greatest collection of Meissen anywhere in Germany. The collection was much dispersed, looted destroyed and forcibly taken in the 1930s and 1940s. Indeed de Waal has bought some of the shattered Meissen plates at auction and had them mended – the mends totally visible – by an old painstaking Japanese method which involves gold among other materials. It was in Saxony, in Dresden where porcelain was first captured for the West and where the first major book-burning event took place in the 1930s.

Library of exile is currently at the British Museum appropriately in a huge wood-panelled room at the end of the vast Edward VII library. For now, it is invisible, oddly and curiously appropriate for what is exile but a way of being erased from your homeland. The artwork itself – pavilion, vitrines – will not go on. But after the British Museum residency, in a museum which Neil Macgregor, its last director, branded as being the world’s museum, the books it contains are given to Mosul where the great library destroyed by ISIS is being rebuilt. And the collection is being continually augmented by the public.

The whole obliquely commemorates one of the best known and eerily prescient remarks in western history, appropriately from Heinrich Heine 1821): Wherever they burn books, they will also, in the end, burn human beings.

In the current installation, books are organised by geography, in sections marked by each country which was the authors’ original home. The vast majority are by writers who left their countries of origin through no choice of their own. Writers from antiquity were forced to migrate between cultures and of course, even languages.

The public has eagerly sent in books of their choice, and not to any imposed restriction on the part of the artist exile has broadened out to include writers who left their native countries by choice. In a sense, this sharpens one’s ideas about home. As the ultimate destination of all these books will be as a component of a renewed library, the definition can be relatively loose. However, it is startling to find – say- James Joyce and Henry James on the shelves. This is because Edmund de Waal felt he did not wish to impose any rigid definition of what exile means on those who were voluntarily sending books. Many books are in of course translation adding yet another layer; and some were written in languages which were not the first language of their writers. The library of exile as first formed here contained books from 58 different countries by 1500 different writers. From Ovid to Tacitus to now: with every genre included, which means one of the most popular books ever written, The Tiger Who Came to Tea, by Judith Kerr.

The charity Book Aid International will move the books themselves to Mosul; the pavilion and its vitrines will no longer exist as the all-embracing installation. The physical form of the library of exile is a way of making ideas concrete. Paradoxically the whole is the least pleasing aesthetically of de Waal’s major pieces. The mix of carefully worked vitrines – the Psalms – the books of all sizes types and conditions – the scrawled phrases on the outside of the pavilion – are awkward even clumsy in a way that heightens the emotional impact of the whole. The library is not a great work of art, but it is a great work of ideas, and a genuinely imaginative embodiment of the life ˙of the mind.

The artwork disperses as the writers of the books it has contained themselves scattered through the world. But this is one of those moments when the physical manifestation, a temporary artwork, conveys in itself a view of human history over millennia. The ideas behind the library of exile remain.

Edmund de Waal, Library of Exile British Museum 2020 – closed until further notice due to Covoid-19

Words: Marina Vaizey ©Artlyst 2020

Photos: Paul Carter Robinson, Sara Faith ©Artlyst 2020