The Courtauld Gallery, London presents Egon Schiele: The Radical Nude; the exhibition surveys the artist’s drawings and watercolours from a controversial and all too brief career – as the artist died aged only 28, succumbing to the Spanish flu, that only three days before had claimed the life of his pregnant wife — yet even in that short time he created some great works of art. The Austrian Schiele along with his fellow countryman Gustav Klimt, shared an interest in the languidly erotic; Schiele loved women.

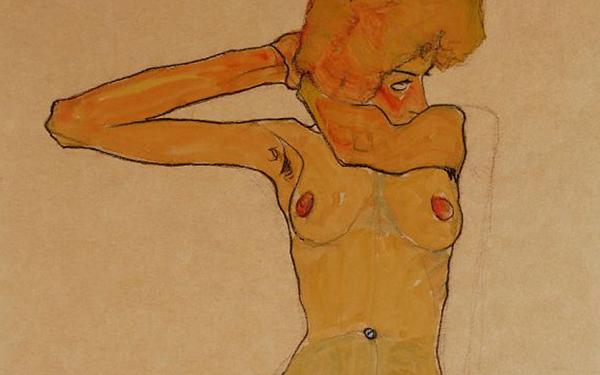

The artist turned the convention of the nude upside-down, depicting his models in contorted positions often displaying their genitalia through Schiele’s focused use of colour; ‘blushing flesh’ exposed with open confidence. Schiele depicted prostitutes, pregnant women, and more than ‘suggested’ the lesbian embrace. The artist was the enfant terrible of his day; breaking many taboos of the image, in fact Schiele’s works at the Courtauld still have that ability. They certainly sparked outrage in early 20th century Vienna; with work that often disposes of the actual identity of his sitter and instead focuses on the nude body as purely erotic form.

The artist’s curve of line and brush often lust obsessively after many of his subjects, but Schiele also focused on a number of self-portraits shown in the exhibition; depicting himself often in sections of trunk, or emaciated hues of brown and blue, as if subconsciously aware of his impending demise. The artist’s vanitas of bodies were created long before Francis Bacon or Lucien Freud would take up the mantle of the uncompromising depiction of the flesh. When viewing Schiele’s self-portraits I was often in mind of Matthias Grünewald’s depiction of the crucifixion; with it’s pain and emaciation of form. Quite the opposite to the way the artist delights in the female body with a focused sense of avarice.

In fact Schiele often thought of himself in quasi-religious terms as ‘the martyr figure’ in his self-portraits – the artist’s ‘Standing Man’ 1913 shows a section of his body as withered and frail, at odds with a man in his 20’s – and is said to relate to a painting titled ‘Encounter’ in which Schiele meets a saint, the work is now lost.

Often breaking high-art’s taboo of depicting explicitness in his work; the artist turns a far more disturbed and melancholic eye on himself. Schiele even depicted himself as Saint Sebastian; when looking at the artist’s watercolours and drawings of himself it is easy to imagine that Schiele had a precognitive ability to foresee the unusually deadly influenza pandemic of 1918 that would infect 500 million souls and kill over 50 million of them – including the artist, his wife, and their unborn child. Whereas in reality Schiele was reflecting a sense of the beleaguered artist; misunderstood by the world at large and destined to suffer for the creation of his art.

Schiele made a number of self-portraits in 1910; three of which are displayed in the Courtauld’s exhibition. The artist assumes a number of identities; depicting various states of anguish. ‘Nude Self-Portrait In Grey with Open Mouth’ 1910, depicts the artist body as skeletal and his eyes a sickly yellow, with arms cropped but still with an allusion to a crucifixion – as the artist expresses his suffering – Grünewald is ever-present in my mind.

Among the rouged and risqué – death and disease are never far away in Schiele’s works on display at the Courtauld. ‘Mother And Child (Woman With Homunculus)’ 1910, is an early nude by the artist; The seductive rear of the model juxtaposes with the malformed body of the child by her side. The work is preoccupied with desire and fertility on the one hand, and death and disease on the other – a daily reality in early 20th century Vienna. Sex and death were the artist’s staple diet it would seem.

Taboos are never far away either; and the theme of death continues quite acutely with the artist’s small and harrowing image of ‘Sick Girl’ 1910. A child is depicted with a pale yellow face; skull-like it appears as if a death mask; the child’s nose seems to have taken on the hollows of a skull, as the child’s genitals are highlighted with a white halo – we not only witness the depiction of the child’s impending demise; but also see the artist reflect on the death of fertility; the death of future life stolen away. The promise of lives lost.

But the artist is always the eager sensualist; with nudes that squat and pose aggressively – bodies with rouged nipples and engorged with Schiele’s obsessions – the artist left Vienna in search of a private, hedonistic lifestyle in the provinces, only to be imprisoned for his erotic art. After-which his work seemed to become even more risqué – but with that lingers the ever present fragility of life; Schiele cannot enjoy the eroticism of female flesh in all its uncompromising sexual brutality without recognising its mortality, its sexualised curve seems literally thin-skinned, death is transparent – with Schiele’s art we have the erotic juxtaposed with the Godless finality of atheistic flesh – which the artist did everything in his power to enjoy – if only for a tragically short time.

Egon Schiele: The Radical Nude – The Courtauld Institute of Art – until 18 January 2015

Words: Paul Black © Artlyst 2014 Photo courtesy of The Courtauld Gallery all rights reserved