The Central Pavilion at the Venice Biennale’s 60th edition is led by curator Adriano Pedrosa, who uses the theme “Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere,” a title which comes from the Palermo-based collective Claire Fontaine’s anti-racism and anti-xenophobia activism in the early 2000s.

“Foreign” is used in the sense of “other” and features artists who are often excluded for their sexuality, gender, poverty, their own indigenous culture or just for being an artist outside of the mainstream. They are all “foreign”.

The title caused some controversy, with Anish Kapoor accusing the curator of “echo[ing] the language of national neo-fascism”. I’m unsure about Kapoor’s comment, and I think the translation of “Stranieri” is closer to “Stranger”.

But despite the controversy over the title and the need for these works to be seen, I found the central pavilion overly didactic, a little disjointed and lacking in any real wow moments. For me, a show with such radical individual components should have been more exciting.

Having said that, there were some stand out works and it is important they are seen and talked about.

The central idea starts with the façade of the building, which has been completely covered for the first time by a giant mural created by the Indigenous Brazilian Huni Kuin artist collective MAKHU (Movimento dos Artistas Huni Kuin). The mural shows the narrative myth of the Earth forming from an alligator.

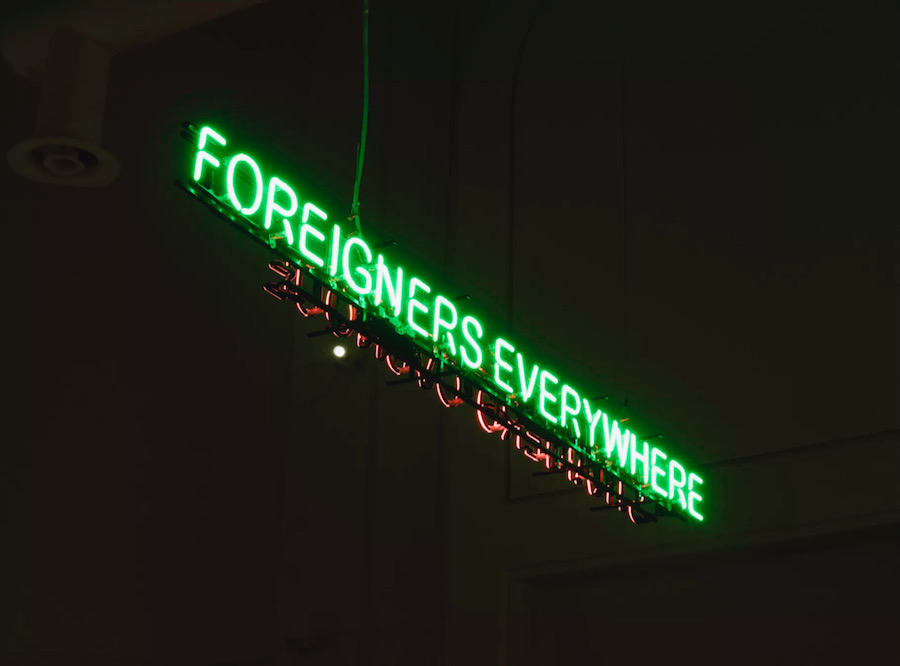

You are greeted at the entrance to the pavilion by one of the neon works by the Claire Fontaine collective, “Stranieri Ovunque”, which gives us the Biennale’s name. They were started in 2004, and to date, they are in 53 languages, both Western and non-western, including several indigenous languages that are, in fact, extinct.

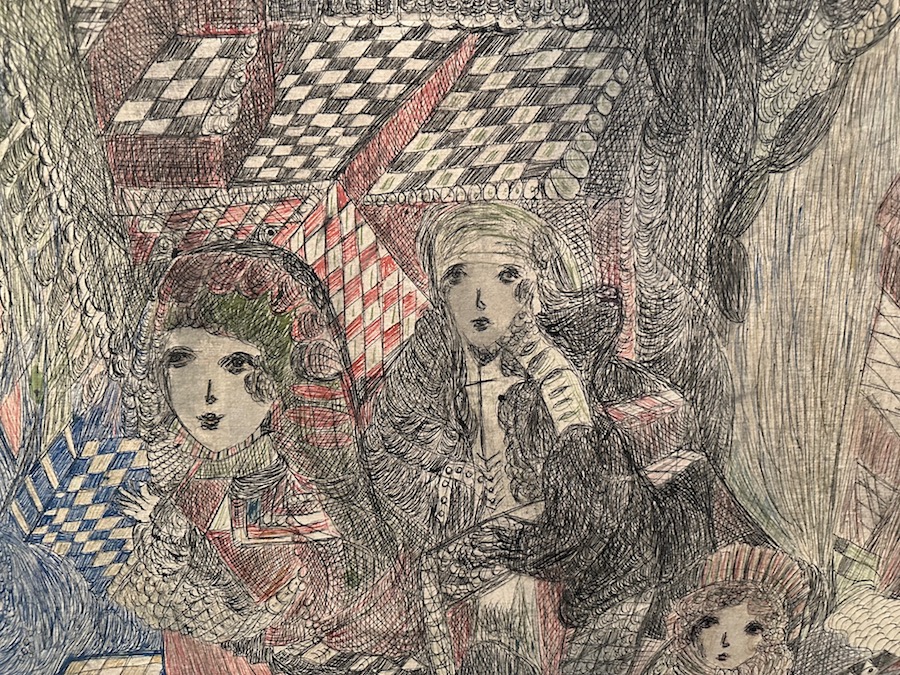

Inside, this is the first time the work of Madge Gill has been presented at the Biennale. Gill was a British outsider artist who, like Hilma af Klint, created her work with the help of a “spirit guide”. The art historian Roger Cardinal, who coined the term “Outsider Art” in 1972, described Gill’s work as having an almost hallucinatory quality, and at the Biennale, they are showing a huge work on calico (Crucifixion of the Soul, 1936), dense with repetitive mark making in her characteristic style, punctuated with hundreds of female faces which are possibly self-portraits or images of her spirit guide. Like many here, Gill’s work deserves a broader audience.

A large-scale textile piece by Liz Collins (Rainbow Mountains: Weather, 2023), a queer feminist artist based in New York City, crosses the boundaries between art and design. The work is a bit Sonia Delaunay-esque in that it is a riotous explosion of colour and geometric abstractions (there’s a lot of queer abstraction going on in this Biennale). Rainbows sprout from a mountain range set against a dark sky, which Collins describes as: “the fantasy of a queer utopia that is just out of reach’.

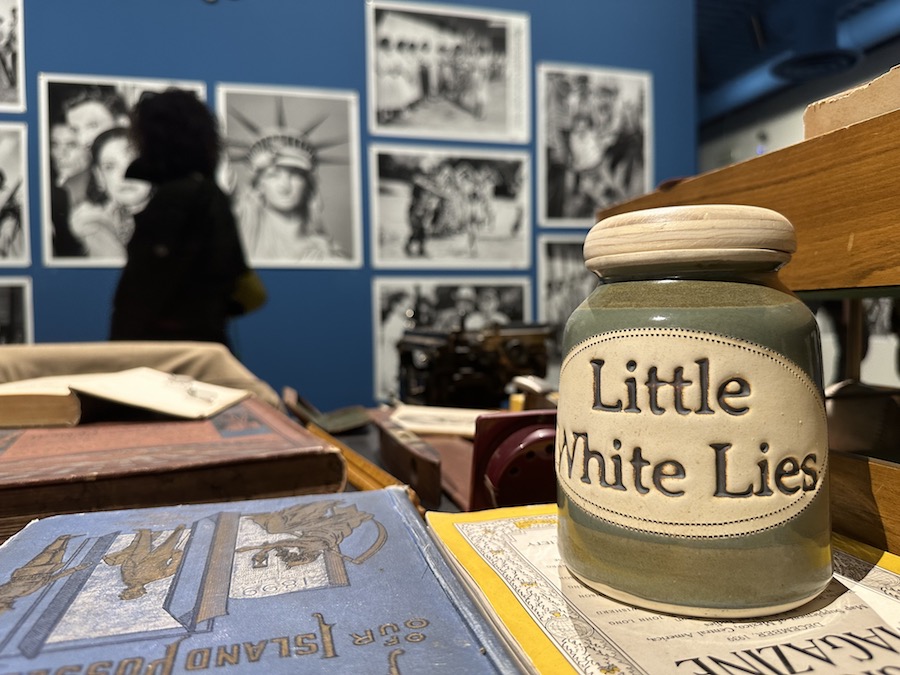

In the lower mezzanine was a wonderful installation by the Puerto Rico–born, Connecticut-based Pablo Delano, who is showing The Museum of the Old Colony (2024), an installation composed of other people’s photographs and ephemera, referring to America’s exploitation of Puerto Rico. One of the most talked about works in the central pavilion, it is set up like an ethnographic museum, but Delano describes it as an “anti-museum” or a “performative museum”. In Delano’s museum, you’ll find a light-skinned Puerto Rican Barbie, a jar of “little white lies”, a classroom desk where indoctrination takes place, and more.

It’s a great work that questions not only colonialism but also the concept of a museum. Who are they for?

Superflex, the Danish artist collective, cleverly subverts xenophobia with their 2002 posters, “FOREIGNERS, PLEASE DON’T LEAVE US ALONE WITH THE DANES!” which were put up in the streets of Copenhagen as a comment on Denmark’s increasingly reactionary immigration politics. This is especially poignant because Denmark’s policy is still escalating and spreading throughout Europe.

Anonymous Homosexual from 2020 is by Dean Sameshima, a queer American artist who lives and works in Berlin and Los Angeles. Sameshima reworks found imagery from marginalised subcultures like the underground movements of queer, punk, and pornography, which, like his paintings, place an emphasis on anonymity.

Elsewhere is work by Ione Saldanha, A pioneering figure in Brazil’s mid-20th-century geometric abstraction movement and an underrated artist who often focused on cityscapes. Saldanha died in 2001, and the Biennale shows several of her ‘Bambus’ from the 1960s and 70s in a large-scale installation. which use dried out bamboo in a kind of sculptural play on painting, with bright vivid colours, and an elegance that belies its materiality.

Another posthumous artist showing for the first time at the Biennale, surprisingly, is Frida Kahlo, in a historical collection, which is on the first level and rather difficult to find (I missed it first time I visited). Kahlo, of course, is the ultimate outsider/stranger/foreigner, so it is apt she is here, showing “Diego and Me” from 1949, in which she wears a huipil, a typical blouse from Tehuantepec, a region of Mexico. The Tehuanas embodied resistance to colonialism, as did Kahlo, who affirms her Mexican empowerment, with the word “Mexico” emphasised next to her signature in the painting.

What is valuable about shows like this, is that they are important in terms of opening up dialogue between curators, thinkers, artists, museum goers, and institutions, and so in that sense, Pedrosa has done a great job. I just would have liked to be jolted out of my chair now and again, rather than just wander round looking at work on walls and nodding my head in agreement.

Words: James Payne

Top photo: Paul Carter Robinson ©Artlyst 2024

60th Venice Biennale 20 April – 24 November 2024, Giardini & Arsenale, Venice

Visit Here