It’s rare to walk into an exhibition and be bowled over (forgive the pun). To encounter work that touches the heart as well as the mind in these insouciant times. Frank Bowling’s exhibition at Tate Britain is one such rare show, reminding us of what painting can do. We can only wonder why it has taken six decades for him to have this sort of recognition. That he is black, that his primary influences came first from Francis Bacon and then from America abstract expressionism, at a time when the art world was shunning depth and existential exploration in favour of surface and irony, must have something to do with it. His acceptance at the Royal College of Art in 1959, a year after the Notting Hill race riots, is not only a testament to his talent but a reminder of the tone of the times in which he found himself an art student.

Abstract Expression has had a bad press for the last few decades. It’s been seen as the art of white males busy climbing on pedestals

From the moment you walk into the Tate show, you know you are in the presence of a significant painter. Born in 1934 in Bartica, British Guiana (now Guyana) Frank Bowling grew up in New Amsterdam where his mother ran a successful store. At the age of 19, he moved to London to become a poet. A period in the Royal Air Force as a regular serviceman was to have a big impact. It was there he met the artist Keith Critchlow who introduced him to the London art scene. After studying at Regent Street Polytechnic and Chelsea School of Art, he was awarded a scholarship to the Royal College where he studied alongside David Hockney, Patrick Caufield and Pauline Boty. Initially rejected because he didn’t have a background in life drawing, he was rescued and funded by the head of painting, Carel Weight. But where Bowling’s contemporaries turned to Pop art, he embraced the poetry of abstract expressionism. A move to New York in 1966 was seminal. His influences became Rothko and Barnet Newman, his concerns history and the exploration of space and time, rather than the iconography and irony of the everyday.

Bowling has said he dislikes the fact the Tate show is chronological but for those who are not that familiar with his output it makes sense. Bowling’s early work is filled with figurative elements. In Birthday 1962, a contorted figure lies on a bed, framed by an open window. The raw isolation, the movement of paint and muscular tension all suggest the influence of Francis Bacon. In Big Bird 1964, we can see the push-pull between the gestural and the abstract. The grid-like background, suggestive of Piet Mondrian on whom he wrote his graduation thesis, creates a formal tension with the violent Bacon-like movement of the wounded birds.

Move to Middle Passage and this large painting, with its melting sunset reds and yellows overlaying bilious greens – the colours of Guyana’s flag – is a reminder of the tragic journeys Europeans forced millions of enslaved Africans to take across the Atlantic. The repeated screen prints of his mother and children are virtually submerged by the fiery colours, suggesting JMW Turner’s 1840 Slave Ship, originally titled Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying- Typhoon Coming On. The veils of paint and use abstraction provide a way to speak of the unspeakable. In 1971 he produced the extraordinary Polish Rebecca, one of six paintings presented at the Witney Museum of American Art show that year, which refers to the Polish heritage of Ad Reinhardt’s wife. With its loose representation of the continental shapes of Africa and Europe, it makes poignant reference to both Jewish and African diasporas.

Around 1973 Bowling started to pour paint onto his canvases as a response to Clement Greenberg’s stance on formalism. This spilling resulted in works such as Tony’s Anvil 1975, dedicated to the late sculptor Tony Caro and the lush Ziff of 1974. Joyful and less angsty than Pollock, they’re a celebration of the texture, sensuality and possibilities of paint. His use of colour is quite simply gorgeous, perhaps almost too gorgeous for modern tastes. The pinks and purples of Devil’s Sole 1980 and Bartica Bressary are like Rothko’s Seagram murals upped a notch to let in more light, life and pleasure. Yet an interest in the existential, infinity and space are there too, especially in the muted surface of Vitacress 1981, with its suggestion of galaxies, distant planets and dark voids.

In Great Thames IV 1988-9 the canvas is covered in gloopy acrylic gel, paint and foam that shimmers like the accumulated debris gathered on the surface the great river. Found objects – lighters, bottle tops, bits of his grandson’s girlfriend’s dress – litter these light-filled paintings that pay homage not only to Gainsborough and John Constable but also to Turner and Monet. This magpie approach implies generosity and inclusivity. Everything, Bowling seems to be saying, as if he were the Walt Whitman [1] of paint, is of value if only we can see it.

Abstract Expression has had a bad press for the last few decades. It’s been seen as the art of white males busy climbing on pedestals. Bowling has rescued it from their clutches, bringing to it his unique voice, melding debates on modernist practice with the vibrancy and freshness of his Guyanan background. Thus turning it from an essentially European movement into a global one.

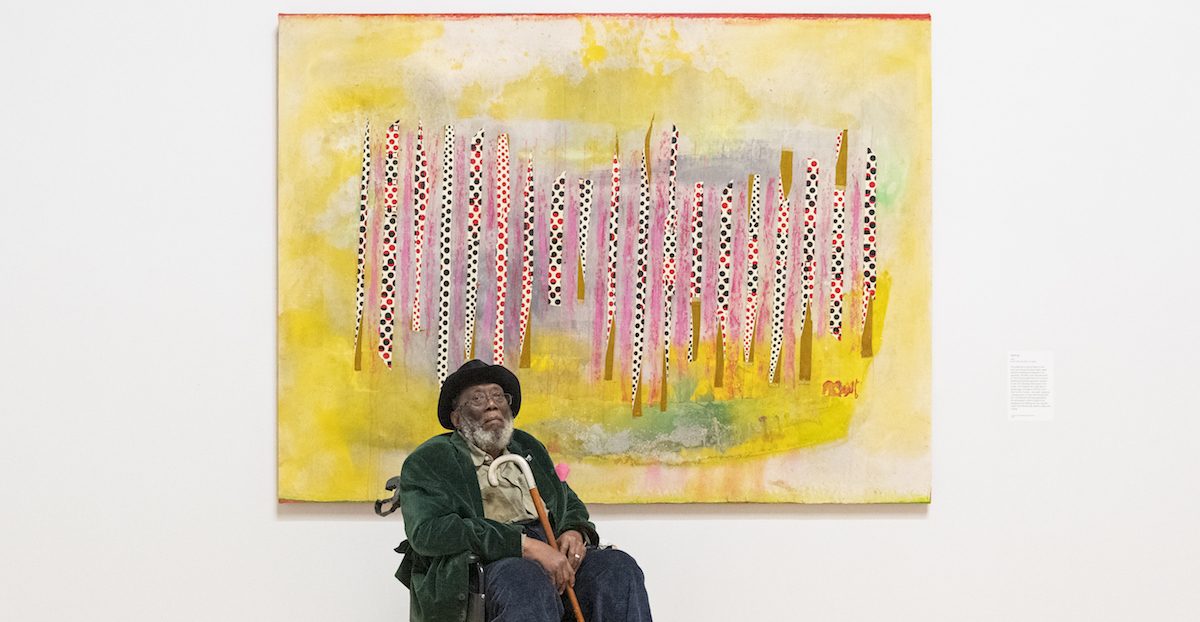

At 85 he is increasingly frail. He orchestrates his bevy of helpers, including his grandson, from a chair in the middle of the room like a conductor, directing the action with his keen eye and his laser pointer. In a world obsessed with youth, too many significant artists tend to be overlooked in their middle years. Some continue in obscurity, but for others, advanced age gives a fresh chance for visibility. When she was in her 90s, a callow young journalist asked Louise Bourgeois what it was like to become famous so late in life. ‘I have’, she answered acerbically, ‘been here all along’.

Frank Bowling has also ‘been here all along’, painting his gorgeous, intelligent light-filled paintings. It‘s just we have been too blind, to distracted by irony and kitsch until now, to give them their due. Luckily recognition has come in his lifetime. It is justly deserved.

Words: Sue Hubbard © Artlyst 2019 Photos Courtesy Tate Britain

Frank Bowling Tate Britain 31 May – 26 August 2019

1. Walt Whitman. American poet 1819-1892. Author of Leaves of Grass. Part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism.

Sue Hubbard is an award-winning poet, novelist and art critic. Her latest novel, Rainsongs, is published by Duckworth.