Gavin Turk’s latest creative enterprise takes place amongst the personal possessions of Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) in the esteemed psychoanalyst’s historic Hampstead home, now a Museum, at 20 Maresfield Gardens.

Following the Nazi annexation of Austria in 1938, Freud and his family managed to escape with all their belongings and set up home in leafy Hampstead. The house remained the family home until Anna Freud , the youngest daughter and also a Psychoanalyst, died in 1982. The centerpiece of the museum is Freud’s dual aspect study, preserved as it was during his lifetime with his extensive collection of Egyptian, Greek, Roman and Oriental antiquities comprising some 2,000 items in cabinets and arranged on every surface. The desk where Freud wrote until the early hours of the morning has on it rows of ancient figures; the walls are lined with shelves containing his large library and of course his famous psychoanalytic couch takes centre stage, draped in an Iranian rug with chenille cushions for added comfort. And so we have the setting for this captivating show.

In 1900 Freud famously published ‘The Interpretation of Dreams’, which is arguably his most important work. It introduced his theory of the unconscious in which through the analysis of the philosopher’s own dreams, Freud maintained that dreams are the conscious expression of an unconscious fantasy or wish not accessible to the individual in waking life. His compatriot Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951), whose sister was one of Freud’s patients, disagreed.

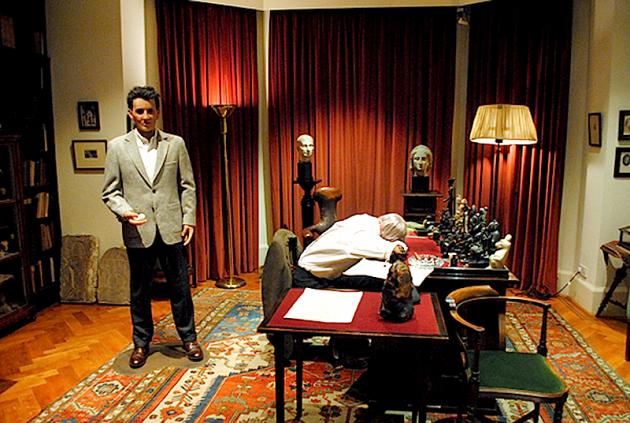

Gavin Turk here displays an intriguing conceptual dialogue between Freud and philosopher Wittgenstein who claimed that Freud’s views on the interpretation of dreams were flawed, believing instead that they required a more logical approach. ‘We are asleep. Our life is like a dream. But in our better hours we wake up just enough to know that we are dreaming’. Wittgenstein told Paul Engelmann in 1917. A life-size waxwork sculpture of Wittgenstein contemplating an egg stands next to Freud’s desk while another figure, who during the opening was spookily alive, is hunched over the desk asleep, breathing deeply and of course dreaming. The waxwork bears a similarity to Turk’s earlier waxwork of himself as Sid Vicious from 2000. Turk’s works effortlessly mingle alongside Freud’s possessions and provide visual explanations to his theories. A large photograph of billowing smoke hangs over Freud’s couch explaining the human tendency to instinctively associate patterns and forms with something familiar in the same way as we do with dreams while referencing Freud’s fondness of smoking. A framed video above the fireplace in the library shows Turk playing a game of chess another interest of Freud’s.

A trio of neon sculptures are displayed on the late Victorian galleried staircase which relate to Freud’s ‘structural theory’ of the human psyche which are fundamental in the development of psychoanalysis: Ego, Id and Super-ego. Upstairs in the exhibition space and in homage to Freud’s cluttered desk, Turk has arranged his own personal collection of objects that relate to his artistic practices, which are annotated with a museum style key explaining each object.

The exhibition brought to mind the Ryan Gander exhibit at the Goldfinger House (also in Hampstead), where pictures from the collection were replaced by Gander’s own works. Similarly, here a Lucien Freud picture of a palm tree in the Dining Room has been replaced by Turk’s photograph of decaying Narcissi referencing both Freud’s interest in the myth of Narcissus and of Dali’s painting of the same title. When Dali visited Freud in London in 1938, he brought with him his painting. Freud wrote the following day to Stefan Zweig, who had introduced them, that ‘it would be very interesting to explore analytically the growth of a picture like this’. There is a drawing of Freud by Dali in the museum collection.

An upright stone monolith in the hallway invites visitors to kiss it. It is really an upturned kerbstone humorously referring at once falling down drunks who have a tendency to kiss the kerbstone and Freud’s interests in love.

Words: Sara Faith Photo: Paul Black © artlyst 2015

Gavin Turk: Wittgenstein’s Dream Freud Museum 26 November 2015 – 7 February 2016 In association with Ben Brown Fine Arts, curated by James Putnam