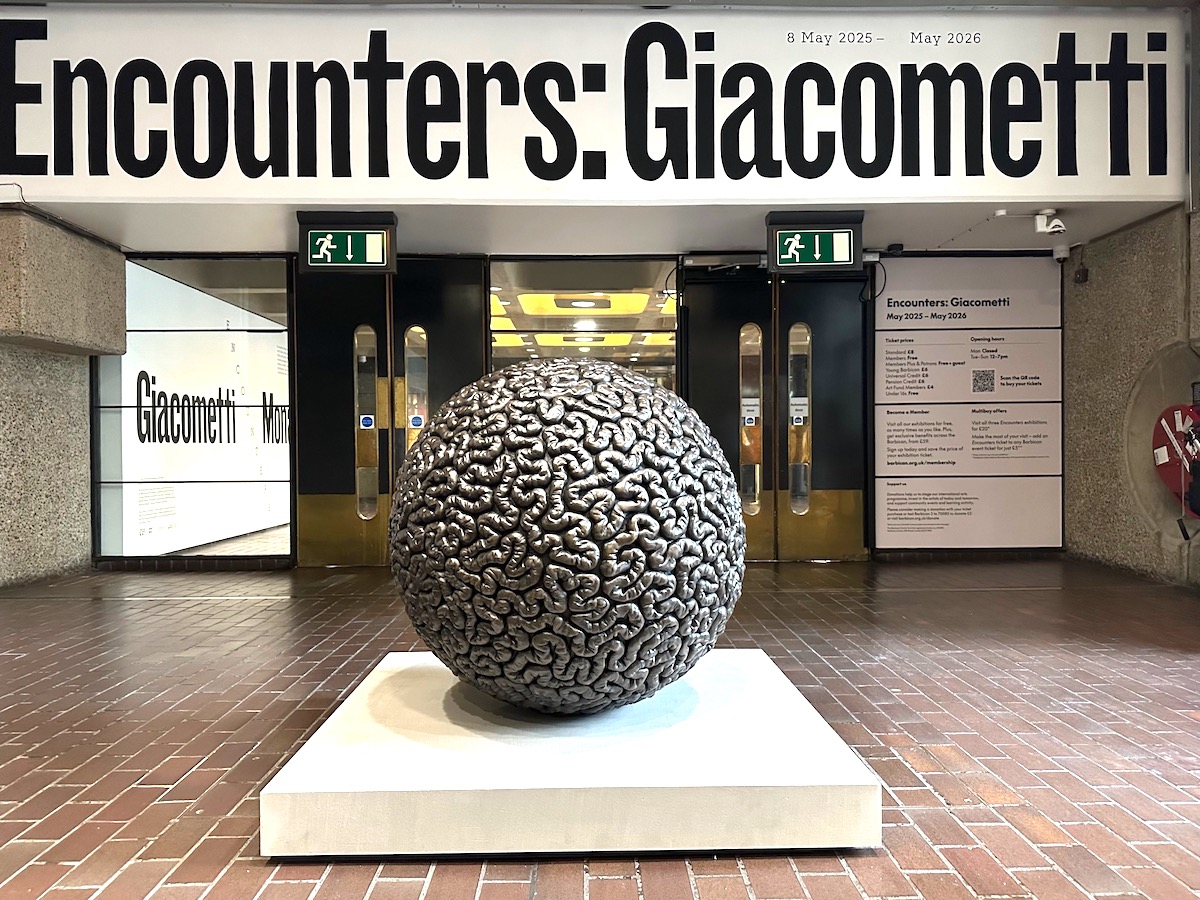

It has become a bit of a ‘thing’ to take a significant 20th-century artist and juxtapose their work with that of a contemporary one. Recently, Edward Munch was paired with Tracey Emin at the Royal Academy. Now the 20th century’s greatest existential sculptor, Alberto Giacometti, is being shown with the Palestinian artist Mona Hatoum at the Barbican. It’s a risky move. Presumably done, not only to show the connections between the two but to add gravitas to the younger artist’s work, which is quite a challenge but one which Hatoum lives up to.

Giacometti approached the human form as something unfamiliar, as if seen for the first time, exemplifying the sentiment expressed by James Joyce, that ‘if you go for the universal you get nothing; if you go for the specific you get the universal.’ Often depicted moving against the horizon, his figures are, to quote Sartre, ‘halfway between nothingness and being…always destroyed and begun once more.’ Having lived through the horrors of WWII, Giacometti’s human forms became tiny, as though he no longer had the right to comment on the human condition, reflecting Beckett’s existential nihilism that there is nothing to express and, anyway, no way in which to express it, coupled with an abiding obligation to express.

Mona Hatoum was born in Beirut in 1952 and forced into exile by the Lebanese Civil War while studying art at the Slade School of Art. At the heart of both her and Giacometti’s practices is the sense of an unstable, unpredictable and violent world. I first encountered Hatoum’s work at the Whitechapel in 2018 when she received the annual Art Icon Award. In a period dominated by stuffed sharks and penile nosed mannequins, I was blown away by the muscular authenticity of her work. Delicate pieces made from threads of the artist’s hair were juxtaposed with works such as Current Disturbance, a large-scale grid of metal cages where light bulbs pulsed menacingly with an audible electric current and spoke of political violence, torture and containment.

Just outside the gallery is a burnt, grid-like lump of steel disfigured by blast holes that turn a formal modernist grid into a sculpture of poignant relevance. This could be any block of flats in any modern war zone, the floors blown out, pummelled by missiles and drones. Created by Hatoum for an exhibition in Beirut, it depicts a world in conflict. In the gallery proper, we are met first with Giacometti’s most violent work, Woman with her Throat Cut. Part insect, part machine, this Kafkaesque surrealist vagina dentata suggests sexual violence, rape and the sort of inhuman behaviour all too often carried out in wartime, where the enemy is seen as sub-human, allowing the other side to treat them with debasing brutality. Nearby is a child’s metal cot where Hatoum has replaced the mattress with cheese wire, so that what should offer comfort and protection becomes a prison exuding violent threat. A collection of crowns in deep red Venetian Murano glass is filled with sand and takes its title, ironically, from Hockney’s lotus-eating Californian swimming pool painting, A Bigger Splash. Though here, instead of water, it’s drops of blood that are spilling around their dry sand interiors.

Giacometti Four Figurines on a Pedestal (Figurines of London, B version) 1950

Giacometti frequently experimented with the motif of the cage. For him, it not only suggested physical imprisonment but an existential sense of the alienated individual in a godless world, dependent only on human will and self-determination to survive. His 1947 The Nose saw him move from Surrealist experimentation to something more directly human. Describing two deaths he witnessed, he wrote: ‘The nose became more and more prominent, the cheeks grew hollow, the almost motionless mouth barely breathed.’ In an audacious move, Hatoum has removed Giocometti’s nose from its original cage, where it poked through the bars, to set it in isolation inside one of her own. Made of latticed wrought iron similar to that used in the windows of medieval buildings, with no entrance or exit, it denies any possibility of escape.

Remains of the Day (perhaps) takes its title from the novel by the Japanese writer Ishiguro. This powerful installation, the charred and ghostly remains of wooden furniture barely held together with wire mesh, suggests something apocalyptic has taken place. Made for the 10th Hiroshima Art Prize, it makes reference not only to that atomic devastation but suggests all the other shattered and twisted remains and ensuing human suffering caused by conflicts around the world today.

Hatoum is good at poetic metaphors, where her simplicity of approach packs a punch. A hospital screen where a spiky grid of barbed wire has replaced the soft cloth that normally gives privacy to a patient triggers associations of torture and political conflict, of borders and communities arbitrarily and cruelly divided. Whereas for Hatoum, threats are largely external and geopolitical, for Giacometti, they are battle zones of the psyche. His concern is not so much with what humans do to each other but what we do to ourselves; how alienated human subjects act. For as Sartre explained, ‘if God does not exist, there is at least one being whose existence comes before its essence…That being is man…who is nothing else but which he makes himself,’ ‘man simply is’ and because there is no God, there is no such thing as human ‘nature’. For Sartre and Giacometti, everything was, in the 1950s, about individual choice and destiny, whereas for Hatoum in the early 21st century, the individual is a pawn to the political ambitions of dictators, despots and those seeking to subjugate other groups for their own gain.

The two artists’ conversation intensifies with Hatoum’s 2007 Round and Round and Giacometti’s 1950 Four Figurines on a Pedestal (Figurines of London, B version), where both play with the scale of the human figure. Hatoum’s continuous ring of tiny bronze soldiers set on a domestic table in an endless circle of ring-o’-roses suggests the relentless cycles of war and killing that taint each generation. Giacometti, on the other hand, arrived at his composition of miniature figures by recalling the memory of four sex workers seen across a room. ‘The distance,’ he said, ‘which separated us…seemed insurmountable….’

This pairing could have gone so very wrong, but what we get here is an existential shriek at the impossibility and absurdity of it all. In an age of despair and violence where we seem to have learnt nothing from the atrocities of the last century, these two artists insist that the labour of making and doing is an act of redemption. The impulse for creativity, as Beckett suggested, elevates us from the slough of despond and cycles of hopeless despair at the human condition, to give the fragile possibility of hope.

Encounters: Giacometti x Mona Hatoum, Barbican Level 2 3 September 2025 – 11 January 2026

Visit Here

Sue Hubbard is an award-winning poet, novelist and freelance art critic. Her latest novel, Flatlands, from Puskin and Mercure de France, was on the Sunday Times best historical fiction list. Her latest poetry collection is Swimming to Albania from Salmon Poetry.