Tate Modern’s new Giacometti show, following hot on the heels of a recent show dedicated to the same artist at the National Portrait Gallery, is nevertheless welcome for the comprehensive view it gives of one of the major stars of the Modern Movement.

“Giacometti still doesn’t get enough credit for what he learned from the distant past” – ELS

In many ways Giacometti’s continuing popularity is a paradox. He was not really a populist, far from it. He stayed in his studio, whether in Paris or during a period of World II stuck in Switzerland, and did what he did. For much of the time, during long periods of his career, he was simply to scrutinise a very small number of people – his brother Diego, his wife Annette, his mistress Caroline, the Japanese critic Hanihara (during a brief period, and with Giacometti’s permission, Annette’s lover) – and try to make likenesses of them. Not so much portraits, as things that would catch their very essence.

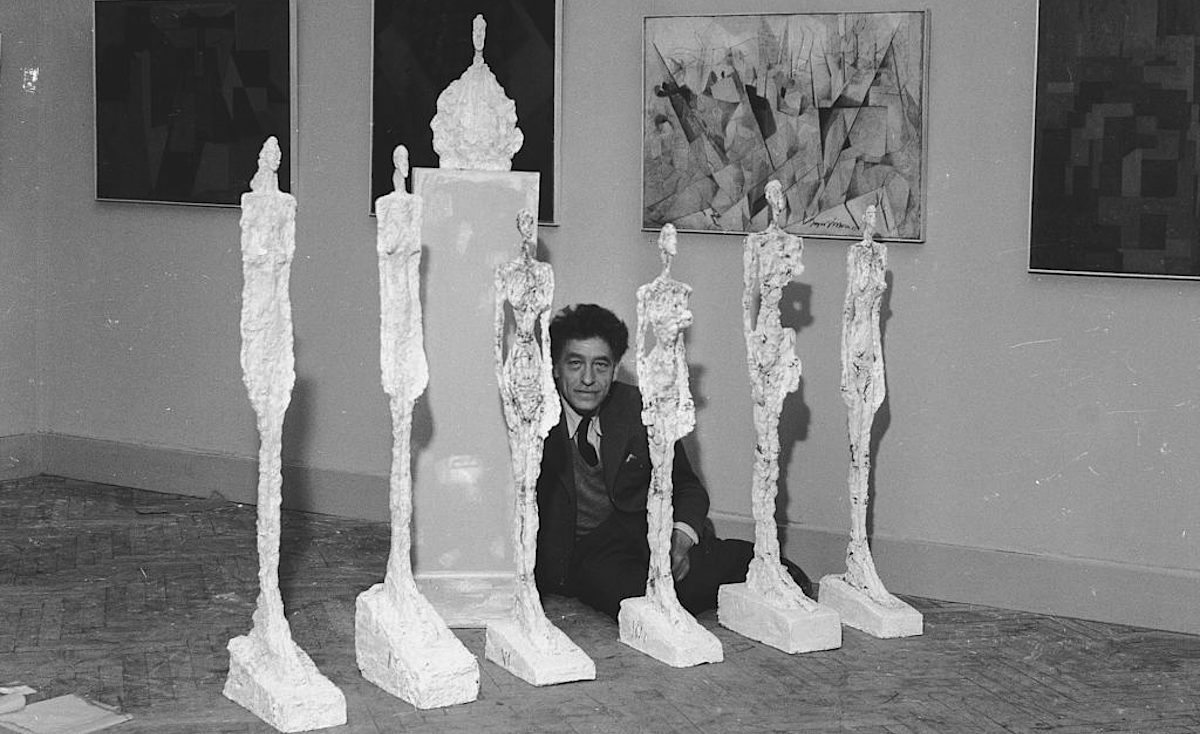

At other times, he made very tall thin figures, on a large scale most usually at the end of his career. At other periods they can range from table top size to aggressively tiny. These figures are not individually identifiable. Once or twice he made separate body parts, such as a long thin arm, which belong to the same way of seeing. Before he progressed to these immediately recognisable human representations – we all think we know what a Giacometti sculpture or a Giacometti painting looks like – he belonged, rather loosely, to the International Surrealist Movement. That is, till he got thrown out by Surrealism’s Pope, André Breton, for not being Surrealist enough.

Socially he moved within a very small circle, a Bohemia of studios, cafés and brothels, located for the most part in Montparnasse, an area of interwar Paris known for its artists. This is, when he wasn’t with his Italian-speaking Swiss family in Switzerland.

He consorted with some of the leading French intellectuals of the immediately post-World War II epoch, which is to say, with Existentialists such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, but it is probably fair to say that they projected their ideas on to what he made when discussing his work, rather than Giacometti taking anything very consciously and deliberately from them. He also liked prostitutes, and semi-criminals such as his mistress Caroline (her name is in fact a pseudonym), and the writer Jean Genet. Altogether, he makes a very odd culture hero for our time. Yet he is, nevertheless, one of the great Modernists whom contemporary post-Modern audiences most instinctively respond to, and Tate Modern, which has I think, despite its splendid new building, been feeling the competition from a revived Royal Academy programme of exhibitions, surely has a big success on its hands.

The completeness of the show – Giacometti from first to last – is a large part of its appeal. You can see a complete career-narrative here, though you may stumble if you try to follow the same story in the stout accompanying catalogue. The preface to this eschews any kind of straightforward narrative in favour of gobbets of information presented in alphabetical not chronological sequence.

Given this arbitrary structure, a certain amount a repetition in these texts is inevitable, and it is amusing – and telling in a negative sort of way – that some of this repetition focuses on one early Surrealist sculpture, Suspended Ball (1930-1), which features, within a metal framework, a plaster ball suspended above and just grazing a reclining plaster crescent. In various interpretations, the sphere is an eyeball about to be sliced, or a testicle being caressed by a tongue. Satisfactorily erotic in both cases, but not so much as to shock any visiting kiddies. Or, for that matter, any puritanical grannies. Intellectuals like something that needs to be interpreted, don’tya know?

I think, speaking personally, I took two things away from this show. Giacometti still doesn’t get enough credit for what he learned from the distant past. He acknowledged a debt to Ancient Egyptian art. Other debts aplenty can be found – to spindly Etruscan bronzes, to drastically simplified Anatolian idols. And of course to African art – this at least is acknowledged in a note to an impressive early sculpture called Spoon Woman (1927). The piece derives from the from the ceremonial spoons made in the West African Dan culture.

The other was a more general impression, though linked to what I’ve said above. Giacometti is the poet, not of intimacy, but of distance. His figures are thin because they are fleeing away from us, into some remote, untouchable distance. They repel our touch, rather than inviting it. This effect is particularly marked when there is a cluster of figures, not necessarily very large, placed on a platform.

Examples here are two groups from 1950, one called The Glade, the other called The Forest. Here is a forest where the imagination can easily wander away and lose itself.

Alberto Giacometti, Tate Modern, 10 May-10 September