To get into Happy Gas, Sarah Lucas’ new solo show at Tate Britain, you have to walk through a gift shop; floating on the sugary peach wallpaper is the repeating photographic image of cigarette orbs (tits) crafted from unsmoked Marlborough lights. Her original Tits in Space wallpaper (on a black background) was first used as the backdrop to her solo exhibition, The Fag Show, at Sadie Coles HQ, London, in 2000. A recurring motif in her work, institutions have variously described cigarettes as a rebel accessory, a phallic stand-in, or a means for independence. For Lucas, smoking cigarettes was about ‘possessing time palpably, stopping to pause and contemplate”. When she quit, she began using them in her work, “this obsessive activity of me sticking all these cigarettes on the sculptures… could be viewed as a form of masturbation. It is a form of sex; it comes from the same drive and there’s so much satisfaction in it.”

Wickedly profane, this scene pays homage to one of the artist’s early installations, The Shop, opened with fellow artist Tracey Emin in 1993, where they sold artworks ranging from printed mugs to T-shirts with slogans like Bitch – a reflection of the horrendous tabloid culture of the time. In 2023, the wallpaper is for sale, but it’s 480 quid a roll. The perfect Lucas way of addressing how institutional recognition influences market value – move house and you cannot take that investment with you – and an elegant example of how her use of everyday yields more ambitious, heavy terrains.

Like recurring motifs, words matter and can be recycled unexpectedly. Traditionally, when TATE gives an artist a solo show, their name suffices for a title. Not one for following traditions, Lucas phoned the curatorial team several weeks before the show and told them, “The title is Happy Gas”. “Perfect”, thought curator Amy Emmerson Martin, “not only does it simultaneously reference laughing gas and how quintessentially British it is to laugh your way through the worst pain in your life – but at the end of this year, the NHS will ban Nitrous Oxide because of the addiction crisis.” One of the leading figures of her generation, Lucas is internationally celebrated for her bold and irreverent work, often exploring the human body, mortality, and a quintessentially British experience of sex, class and gender. Happy Gas brings together more than 75 works spanning four decades, from breakthrough early sculptures (The Old Couple, 1992; Bunny, 1997) and photographs (Fat, Forty and Fabulous, 1990; Eating a Banana, 1990) to seminal (Mumum, 2012; DICK ‘EAD, 2018) and brand new works being shown for the first time.

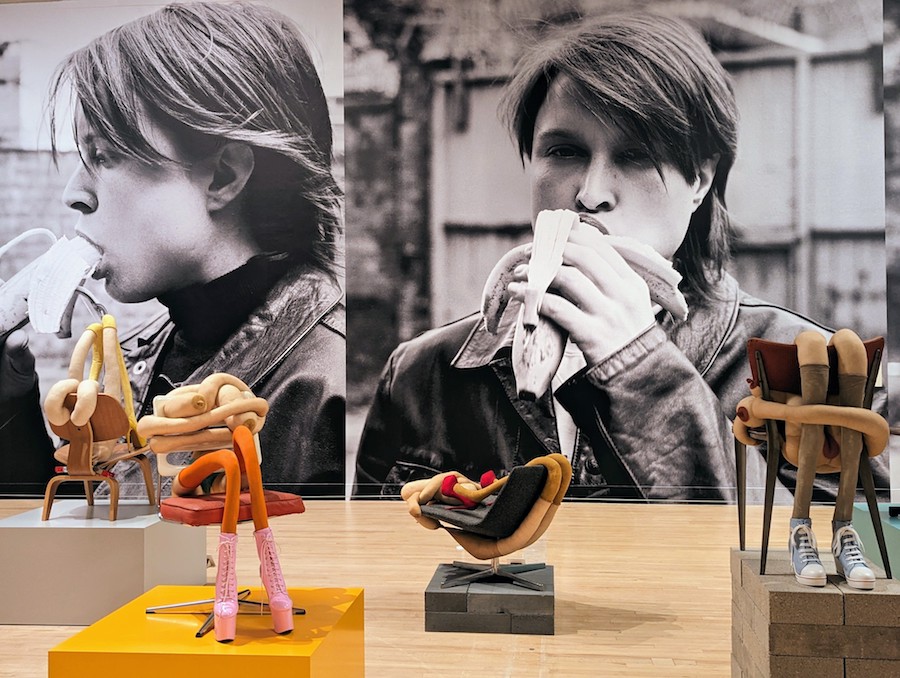

Whilst Happy Gas is a survey show, it was devised in close dialogue between Amy Emmerson Martin and Dominique Heyse-Moore and presented in the artist’s voice. The entire show is a mise-en-scene that delights in the reunion of so many iconic works as a form of installation art. The centre stage is the chair, variously reinterpreted, with different iterations of Bunny. “I decided to hang the exhibition mainly on chairs. Much in the same way that I hang sculptures onto chairs.” Her gatherings of sculptures have the quality of mad school reunions; these are surrounded by giant repeating self-portraits in photographic wallpaper or unforgiving faux cement walls. As we progress through the rooms, we follow how Lucas developed her quirky lexicon in appropriating everyday materials and language and marvel at her freedom of improvisation with forms.

No matter how familiar you are with her work, the result is sensational and arresting. This show ties in elegantly with the Tate’s recent rehang, “so fitting when at Tate Britain we have been presenting an entirely different perspective on British Art through rehanging our collections.” Maria Balshaw, director Tate. It is a physically and technically difficult show, and the installation team headed up by Mikei Hall deserve special mention. Equally, the expanded imagery is excellently proportioned to the sculptures; looming above The Old Couple, 1992 – made from two chairs, a wax penis and a set of false teeth – is Chicken Knickers, 1997, which causes your stomach to lurch with its implied nudity. Next door, we have a gallery of Lucas’s signature soft sculptures made from stuffed tights, as if the now iconic Bunny, 1997, had reproduced a whole cohort of reprobates. The rough and the smooth, the coral and the black, the smashed-up-burnt-out-wreck-of-a-body and its gentle cocooning with unsmoked cigarettes. Her uncanny ability to highlight particular aspects of Britishness and field them into more ambiguous or existential conversations gives Lucas an international appeal as unquantifiable as David Bowie.

Sarah Lucas came to fame in the 90s. Thank Lucas for her hilarity – I mean, how else could one respond to the pernicious lad culture (toxic masculinity) that proliferated London in the 90s? Tate Britain’s exhibition begins with some of Lucas’s early works from this era, including those made from tabloid newspaper spreads like Sod You Gits 1990 and Fat, Forty and Flab-ulous 1990. These introduce the artist’s use of innuendo and wordplay and her interest in feminist discourse and representations of the female body. I found this profoundly triggering. For someone who came to live in Britain in the ’90s, I was reminded of my misunderstanding of social norms – why was this nation so obsessed with toilets? Then there was the pantomime sexism and perverted tabloids – seeing Louise Redknapp’s innocent mug shot in a line-up of potential candidates for the best breasts, I gasped. Yes, it was like that.

And there is Lucas at the far end of the room, skulking in an oversized black dinner jacket and white vest, holding a dead fish (Got A Salmon on #1, 1997). Beneath this image, a yellow gloved hand attached to an empty chair moves back and forth. Impossible for your mind not to offer the word – wanker. Fun fact: in 1973, there was an unprecedented spike in boy babies; all these lads were coming of age in the 90s, and they dominated the culture. “She turns the table on sexism by literalising and surrealising it in stark three dimensions, thus joyously turning the tables on its negative power,” says Tate director Alex Farquarson. How I wish I had paid more attention to her work then.

Lucas loves a bit of bathroom humour. Her first solo exhibition was The Whole Joke (1992), followed by Penis Nailed to a Board the same year. Around this time, Lucas seized on the idea of using furniture in her sculptures as hard scaffolding (skeletons?) for her soft, nylon-filled body bits. The chair has always been a vehicle for icons, with designers – Charles and Ray Eames or Marcel Breuer Cesca – expressing their vision through reinterpretation. For Lucas, the point is neither the beauty or innovation of the chair but what we do in the chair – and how that doing often happens without thinking. In the central gallery, we find works on chairs made between 2019 and 2023, including 16 new works displayed for the first time. Some show a return to the found objects and stuffed tights of Lucas’s early work, such as SUGAR 2020 and CROSS DORIS 2019, while others are rendered in finely cast bronze and resin.

Typically, a chair is reserved for passive spectators, lounges and waiting rooms. In Happy Gas, we – the audience – are asked to walk by and observe. Bonkers and irreverent, whilst anthropomorphising the chair, it also becomes a vehicle for her irrepressible sense of humour and enormous resourcefulness. This is the artist who can fry two eggs and have the whole art world talking for decades. Handsome, fearless and charismatic – whether taking a salmon for a walk or making boobs out of cigarettes, Lucas seems to laugh the low out of everything and leave us with an art high. As Farquarson says, “It gets under your skin, and it stays with you.”

The exhibition explores the growing range of more permanent materials used in Lucas’s sculpture, including bronze, resin, and concrete. This change in materiality was a major departure from the techniques she had been using for decades, including tights and stuffing, cigarettes, and food, which were chosen for their immediate availability. Examples include concrete furniture like Eames Chair 2015, bronze casts of stuffed phallic shapes like DICK’ EAD 2018, and giant cast concrete vegetables such as Florian and Kevin 2013, installed on the lawn outside Tate Britain to coincide with this exhibition. This shift towards more lasting materiality seems concurrent with her institutional and academic recognition. However, it also belies a confidence in her cast of characters that will likely outlive her flesh and blood.

Walking through this exhibition, I remember my daughter’s impression of a “road man” and how much we laughed at her pretending to be louche. But actually, it’s not funny. There were so many things that were not okay when I was a young woman that are still not okay – but I like the Lucas way of laughing them down. Interestingly, Lucas began her artistic education at The Working Men’s College (1982-83), then went to Goldsmiths College, graduating in 1987. By 1988, she would participate in an exhibition defining the British art scene at the turn of the century – Freeze – along with contemporaries Angus Fairhurst, Damien Hirst and Gary Hume. Hanging with those lads, she challenged the British art world and made an indelible impact on the cultural landscape, and she continues to do this today. To reiterate the words of Balshaw, “Thank you for continuing to challenge and confront the narratives that so often confine us or are imposed on us, for being the renegade trailblazer that we first saw in the 90s and that we see here.”

Without giving away what happens in the last room, because you must go and see this show, one recurring motif in Happy Gas captured my imagination – the black cat. A leggy feline friend is loitering around the base of various sculptures, looking soft but cast in bronze. If you have a cat, you know how audaciously promiscuous but fervently loyal they can be. Unpredictable, highly sexual, and supremely agile, a cat is the perfect trope for an artist who avoids categorisation.

Sarah Lucas – Happy Gas – Until 14 January 2024

Words/Photos: Nico Kos-Earle Top Photo © Artlyst 2023