The Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam is currently presenting a particularly experimental and mysterious artist from the Dutch Golden Age: Hercules Segers. This exhibition is the first complete exploration of the artist’s oeuvre, piecing together the fascinating strands of Segers’ practice in an attempt to separate fact from the apocryphal. The show is also rather neatly juxtaposed with the exhibition of another artist of that Age: Frans Post. The juxtaposition is one of an obsessional and mysterious depths, set against a lighter exploratory wonder – yet both artists employ imagination and the surprisingly flexible nature of their individual practices.

For some time Segers was a lost artist, lost to the history of Dutch painting – even though he was in fact collected by Rembrandt who owned as many as eight of the artist’s paintings – with a number of works my Segers at first being wrongly attributed to the artist. He was rediscovered in 1870, and it is believed that the artist’s oeuvre was indeed extensive, even though there is now a fraction of the works surviving, having been lost to time, or perhaps misattributed over the ages. Due to this historical happenstance, there is a curatorial detective story running through this particular collection of surviving works, one epistemic in narrative.

There is also a beautiful efficiency to the curation of this exhibition; the viewer is presented with multiple prints from a single plate and the visual history of its variation, often in contrast to the same subject in paint, as we are taken on a temporal journey through a single image. Segers’ practice is not an average one even from this period, the division between representation and imagination is a blurred definition from early in the artist’s work; as Segers adds fictitious mountainous scapes to the flat Dutch expanse, bringing with them a form of early Romanticism, turning these early landscapes into hybrid fantasies.

In fact, there is something extremely contemporary about Segers. The artist created what his contemporary, Samuel van Hoogstraten, described as ‘Printed Paintings’. The artist did – what was at the time – the unthinkable: he used painter’s materials, and printed with oil paints on colourful backgrounds, using linen and cotton. This was a true subversion and hybridization of practices from the period; it would seem that the artist represented the vanguard of experimentation. It was also discovered that Segers was the first European artist to use Japanese paper, some twenty years before Rembrandt. The artist’s work is consequently regarded as a precursor of modern art in general: in fact, nothing so experimental in print was attempted again until the 20th century – after Segers had been rediscovered. The resulting display is an au courant experience for the viewer: hybrid prints created through the subversion of traditional practice, made hundreds of years before any other artist would re-attempt the process. A Post-Modernist act committed in a pre-Modernist era.

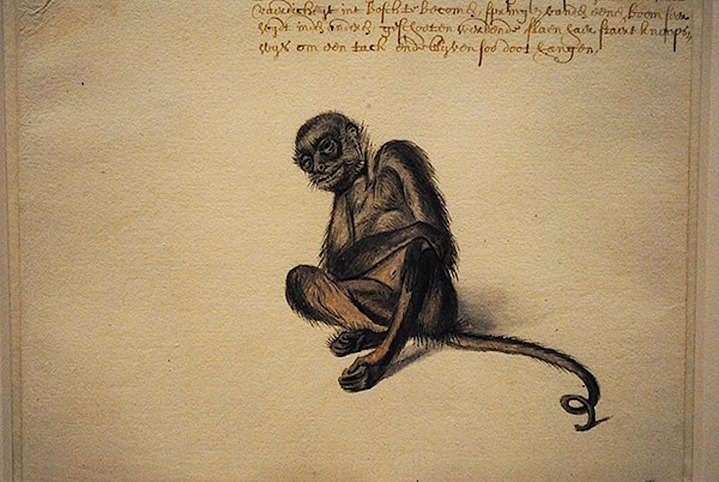

The same prescient subjectivity can be observed in the Rijksmuseum’s exhibition of works by Frans Post, in which 34 animal drawings by the artist make their first public appearance. These animal studies were until recently completely unknown, that is, before they were discovered at the Noord-Hollands Archief, in Haarlem – the birthplace of both artists. In 1636 Post travelled to the Dutch colony of Brazil, where for seven years the artist studied Brazilian flora and fauna, which subsequently inspired Post’s paintings. It was always suspected that the artist created preparatory studies of the animals in his works – as certain motifs are repeated in Post’s series from the period – but no drawings associated with these paintings were ever attributed to the artist.

The decision to add stuffed animals to the exhibition – the same species present in Post’s sketches – borrowed from the Naturalis Biodiversity Centre in Leiden – not only acts as a signifier of the Dutch Golden Age’s nature of enquiry, but also adds a playful touch to the show: a lighter leitmotif than Seger’s obsessive compulsive detail. But it is in fact that nature of enquiry and detail that is so present in both artists work. Post’s enjoyment of his practice bleeds infectiously from his paintings, as although painted in the early 17th century, these Brazilian landscapes display a colour palette more akin to the Expressionism of the 19th and early 20th centuries: a vibrancy reflecting the artist’s environment – and that exploratory wonder – the truly vibrant shock of the new.

Words: Paul Black @Artjourno