A group of recently opened shows, very different from one another, raise questions about the direction the visual arts are now taking.

There is, for example, a strong contrast between Is This Tomorrow? at the Whitechapel Art Gallery and the David Bailey photo show at Gagosian’s West End gallery in Davies Street.

There is no doubt about the focus and subject matter of the Bailey exhibit. Subtitled ‘The Sixties’, the celebrity culture of that now distant decade is exactly what it is about. There are, however, some of his subjects who are still alive – Michael Caine, David Hockney – and others who are gone but unforgotten, such as Andy Warhol. There are supermodels, then a new species; rock stars, specifically the Rolling Stones and two (out of four) of the Beatles, and – yes – a group of three Kray Brothers, smoothly sinister. One is struck not only by how lively the images are but also by how durable these various reputations have been. Bailey knew how to get through to all of them, how to make them project their true selves to the camera. Collectively, the exhibition offers an image of how society, British society, in particular, had begun to change during this crucial decade. Also, how heterogeneous it was becoming – a process that has continued apace, but without forgetting its origins. Though it is, in fact, a historical record, this event seems very ‘now’. As a society, we adhere to the same values, worship at the same, or at least very similar, shrines.

The exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery strikes a very different note. It is a follow up to a famous show held at the same gallery in 1956. In that case, the title was a confident statement, not a question: This Is Tomorrow. A lot of still-famous names were involved: William Turnbull, Richard Hamilton, Eduardo Paolozzi, Alison and Peter Smithson. It is now remembered chiefly for its poster – a bodybuilder carrying an enormous lollipop (marked ‘Pop’ in case you didn’t get it), together with a tin of ham and a reclining bare-breasted nude. This image is generally thought to have marked the very beginnings of Pop Art.

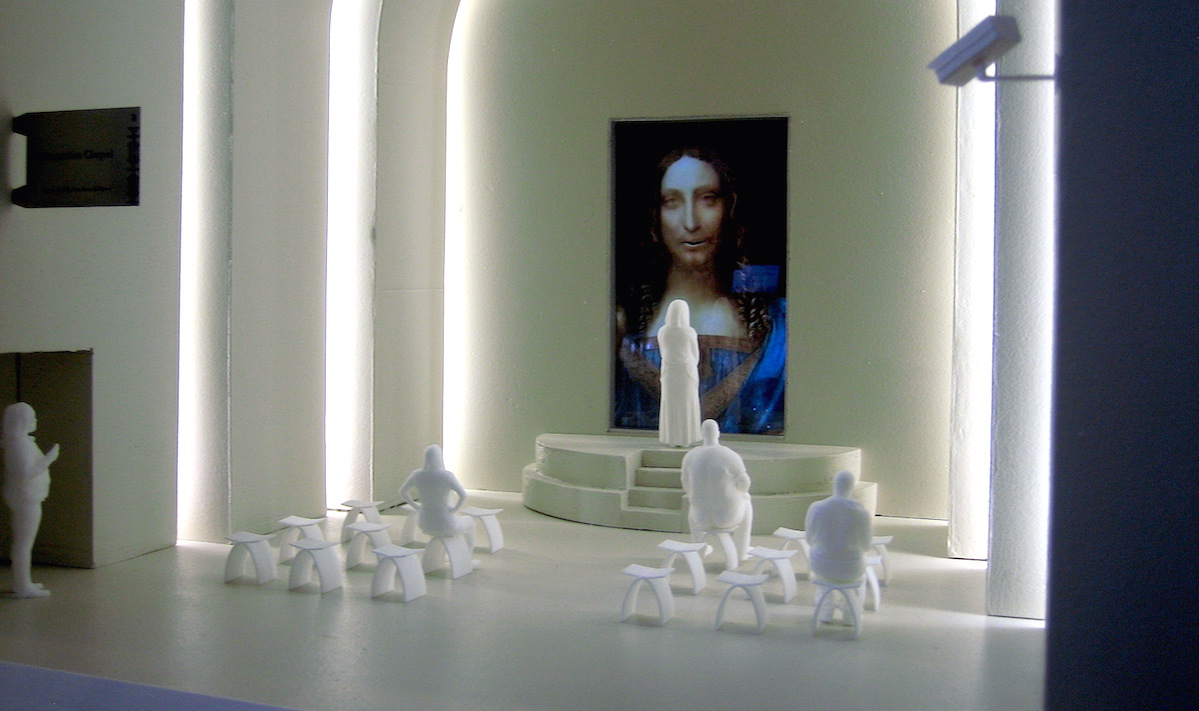

Is This Tomorrow offers a very different vibe. Figurative images are scarce, though not entirely absent. The ground floor space is devoted, largely, to what one can only describe as a bewilderment of turnstiles, more reluctant to let you in than to let you out. You progress upstairs, past a banqueting table laid with books and catalogues, rather than with anything you might possibly want to eat, and on an upper floor, you reach the best thing in the show. This is an installation, by Simon Fujiwara in collaboration with David Kohn Architects, described as ‘a miniature museum’. Duck down, burrow into the structure confronting you, and, when you can haul yourself upright again, stand on a little platform where you find yourself confronted with dinky versions of Leonardo da Vinci’s is-it-or-isn’t-it-actually-by-him Salvator Mundi, housed various forms of doll’s house-sized museum setting. As the handout tells you: “The Salvator Mundi Experience explores the plausible proposition of a world ‘post-art’, ‘post architecture’, even ‘post-culture’ as we know it.” How depressing! Still more depressing because you probably have to queue up to see it. The installation is anti-democratic, at least in the sense that it can only be visited one-at-a-time. All the same, it does make you think. Or that’s what it did to me.

More conventional offerings this week are less depressing but don’t seem to offer a road towards anything really new. Two of them are in Cork Street, long a traditional location for new art, but now in the grip of radical physical change. Both offer work by figurative painters. One, at the Dandini Gallery, offers work by Philip Humm. There are lively, often ironic versions of traditional motifs, plus some elegant figurative sculptures. One of the paintings, called Revolutions, is a somewhat downbeat paraphrase of Delacroix’s Liberty Guiding the People, where Lady Liberty, waving her tricolour, seems to attract no followers.

The other, at the Mayor Gallery a few doors away, offers new work by John Kirby, a British painter for whom I have long felt a great respect. The images are subdued and strangely melancholy. For me, the most memorable is one that shows a young black woman in a long white dress, standing alone in a vast unpeopled landscape.

The two galleries mentioned, on the east side of the street, are separated by a just-completed huge new building. The empty ground floor advertises itself as a gallery, all ready to be filled with art. One wonders what kind of art, and who will be coming to buy it, here in Brexiteering Britain? The prospects can’t be that good.