Japanese art is having its time in the sun, with three British galleries putting on summer shows that illustrate the variety and adaptability of the country’s woodblock printing tradition.

At the Dulwich Picture Gallery, Yoshida: Three Generations of Japanese Printmaking will introduce to the British public the prints of Yoshida Hiroshi and his wife Fujio, their sons Tōshi and Hodaka, Hodaka’s wife Chizuko and their daughter Ayomi. Opening on June 19 and running through November 3, the exhibition will bring together for the first time in the UK – and Europe more widely – the creations of an artistic dynasty famous in Japan.

The prints on show span almost a century and a half of artistic evolution: The patriarch of the clan, Hiroshi, born in 1876, and Fujio were pioneers of the early 20th-century Shin-hanga movement, bringing Western influences to traditional Ukiyo-e prints of landscapes, actors, and courtesans. Their sons ventured into modernism and abstraction. Granddaughter Ayomi, born in 1958 and still working, moved beyond printing and is now known for deconstructing the woodblock process, combining hundreds of blocks and the chips carved from them into room-sized installations.

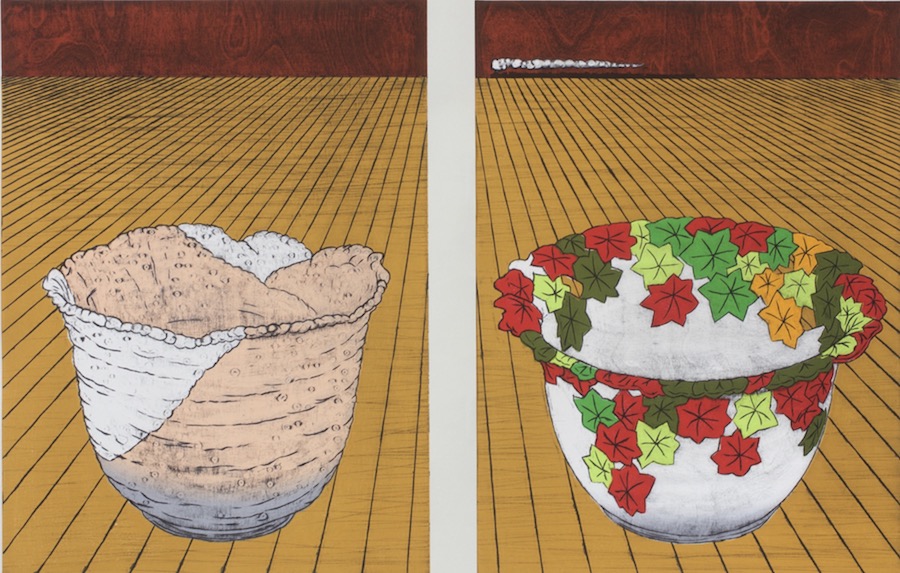

In Chichester, the Pallant House Gallery will show Nana Shiomi: Her Interpretation from August 3 to October 13. Born in Japan, Shiomi completed her training at the Royal College of Art and now lives in London. Combining relief and intaglio techniques, her woodcuts fuse Japanese woodblock printing with European influences, referencing artists such as Paul Cezanne, Marcel Duchamp, Albrecht Dürer, and Giorgio De Chirico.

Her work, merging icons of Japanese life with populist and philosophical concepts, explores the interchange of culture between Britain and Japan, the nature of duality, ideas of East and West, National and International, and the change of viewpoint that a shift in perspective brings.

In a more traditional vein, Watts Gallery, nestled in the Surrey countryside near Guildford, currently shows 50 works from a collection of 19th-century Japanese woodblock prints owned by the art historian and writer Frank Milner.

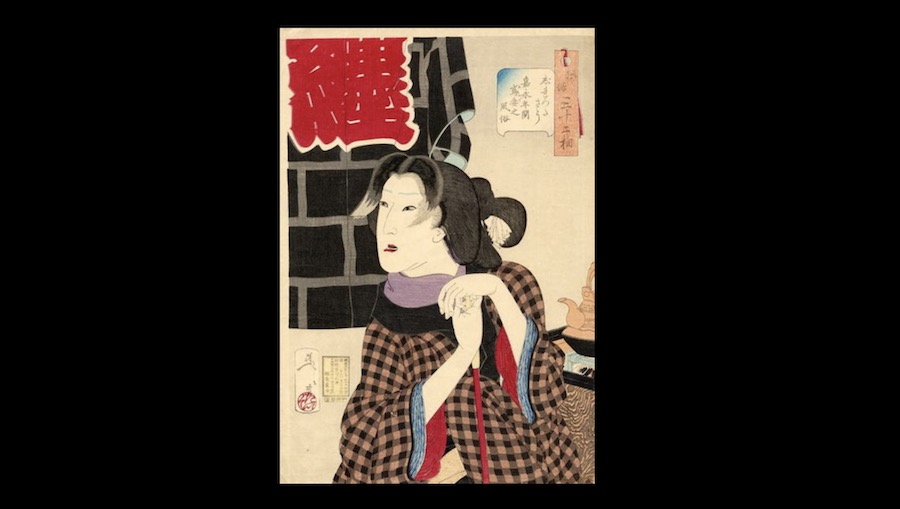

Titled Edo Pop, the show is home to the vibrant entertainment scene in Edo, as Tokyo was then named from 1825 to 1895. Edo was the world’s largest city, a bustling metropolis with a population of over a million and a teeming pleasure district of brothels, tea houses, and eating places known as Ukiyo—the floating world. (Top Photo)

Pictures of the floating world, Ukiyo-e, were a form of popular art. Print editions connected the entertainers—geishas and prostitutes, sumo wrestlers and Kabuki actors—with their devoted fans.

Running until 06 October, Edo Pop takes you on an amusing, fun, and highly colourful journey. It reveals aspects of an intriguing and captivating society, from domestic scenes to samurai dramas and tales of passion, that had been closed to the world for 200 years.

While the finest and best-known artists of the genre, such as Hokusai, lived and worked some decades earlier, the show is mainly dedicated to the mid-to-late 19th century, a period in which tradition and modernity collide. Celebrating Edo in its uninhibited heyday, it portrays people of every level in society enjoying festivals, performances and theatre.

“These prints were very popular in Japan and affordable,” says the show’s curator, Laura MacCulloch: “They also became very popular in Europe. Colour printing was very advanced in Japan. They were far ahead. Many artists collected prints, including Rossetti, Whistler, Monet and Van Gogh. These works influenced their art”.

Among the artists who came under the influence were the painter George Frederic Watts and his ceramicist wife, Mary. The Watts Gallery was founded in 1904, and its championing of Art for All chimed with Japanese craft printmakers’ popular spirit and affordability.

While images of theatrical and sporting celebrities, geisha, and beautiful oiran—high-class courtesans—are typical of the genre, MacCulloch added that depictions of domestic and everyday working scenes are relatively unusual.

Celebrity culture is represented in prints of stars of the day, such as Kikugawa Eizan’s Oiran (1830), Utagawa Kunisada’s sumo wrestler Kagamiwa of The West Side (1846), or Toyohara Kunichika’s Geisha Kogiku Looking at Photographs (1870). But every day, there are touching moments in the anxious wait of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi’s Fireman’s Wife (1888) or a surprisingly tender mother with a crying baby.

The mise-en-scene of the exhibition is stunning, with a pink background and vinyl prints of the artwork blown up to extraordinary effect, giving it a contemporary edge.

To complement the exhibition, the contemporary Japanese printmaker Hiroko Imada created a beautiful cherry blossom installation in the sculpture gallery.

If you’re taking in the show, remember to visit the nearby Watts Cemetery Chapel. Mary conceived it as a Romanesque mortuary memorial in red brick, with lavish terracotta relief decoration and a neo-Byzantine-painted interior. It’s a unique, grade-1 listed Celtic Revival Art Nouveau folly.

Top Photo: Edo Pop