The new book on Joseph Wright of Derby by Matthew Craske is a massive tome. Published by the Paul Mellon Center for British Art, it is entirely worthy of the artist’s high reputation.

In many ways, Wright was an exception in the English art world of his day – ELS

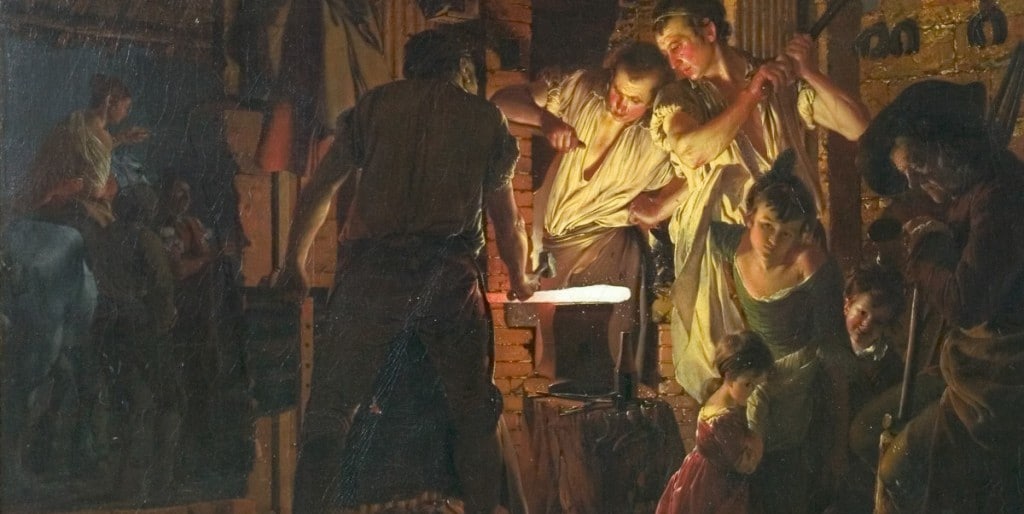

The fascinating thing is that it does so much to change the nature of that reputation. Wright has been made famous in recent, or semi-recent art historical scholarship as being a pioneer in the representation of science. Paintings such as A Philosopher Giving a Scientific Lecture on the Orrery (1768) and An Experiment on a Bird in an Air Pump (also 1768) are seen as key works documenting 18th-century scientific rationalism. In fact, as Craske sets out to prove, Wright’s work was the embodiment of the early phases of the Romantic sensibility. The book is sub-titled ‘Painter of Darkness’ and as one looks through the illustrations, it is clear that this was very much the case. Wright tended to paint pictures in series, especially during the later phases of his career, and the most sustained of these series is one of paintings that show Vesuvius in eruption.

Wright made his Grand Tour to Italy relatively late. He was a mature, fully established artist when he went there, and the ferocity of Vesuvius was what he wanted to show his patrons. He painted it largely as it appeared when erupting at night. The ‘Painter of Darkness’ label also applied to the majority of his other productions.

In many ways, Wright was an exception in the English art world of his day. He lived in his native town, Derby or close to it, with excursions to places such as Liverpool. His trip to Italy was his one big trip abroad. As he aged, he seems to have become increasingly reclusive. His major patrons were often members of the local gentry, at its upper levels, though he did also market his wares in London. He was originally a member of the Society of Artists, then a rather reluctant and discontented member of the Royal Academy. Where he never progressed beyond the rank of Associate. He was canny about publicising his work through prints – not made by himself, but by professional engravers, using the new technique of mezzotint, which was well suited to his chiaroscuro effects.

Though he made portraits, his chief output, in addition to dramatic landscapes, was ‘history pictures’, then considered to be the highest rank of art, and also not thought of as being in any way a typically British genre. His contemporary Sir Joshua Reynolds, chief founder of the R.A., was pretty much exclusively a portraitist.

Wright was also a literary painter, in the manner of the academic artists who practised in Victorian times. Many of his paintings refer the viewer to literary texts, both ancient and modern. Matthew Craske’s text offers are large number of relevant quotations from poets who were Wright’s friends. Pretty well all of them have vanished from posterity’s sight. It is also perhaps worth noting that only one of these now obscure versifiers was a female and that women do not appear among those cited in the book as being the painter’s close friends and patrons. He did, however, sometimes paint women as emblematic or allegorical figures. In this sense, the cultural world that Wright inhabited seems very different from the one we have today.

What does not seem different is the insistent moralism, and the desire to instruct. Like many current figurative artists, Wright wanted to tell his viewers how to react to a world full of rights and wrongs. Very occasionally, this led him to subjects that echo those that are insistently examined today. There is, for example, just one painting that echoes the current preoccupation with ethnic minorities. It is called The Indian Widow and shows a desolate Native American woman sitting alone, mourning for her spouse. There are, however, no paintings about the slave trade, which was going strong in the painter’s lifetime.

More often, the messages in Wright’s paintings are both culturally complex and at the same time quite direct. For example, a painting entitled Miravan Breaking open the Tomb of His Ancestors (1772) shows a prince with an oriental turban watching workmen open at his instructions a very western-looking sepulchre to find, not the gold he expects, but a bare skeleton. Horrified watchers peer in from the door of a half-ruined building. The moralistic message is – quite literally – hammered home.

In an odd way, this doesn’t seem so different from the moralistic art we are quite frequently confronted with today.

Read More About Joseph Wright of Derby