The old and the new sit easily with each other in Amsterdam, especially now that its three powerhouse museums have all been reopened following extensive restructuring. So a weekend there was a good chance to see how the past is picked up in current trends. To that end, I visited:

John Chamberlain’s Naughtynightcap (2008), Ritzfrolick (2010), Fiddler’sfortune (2010) and Wishingwellwink (2010) outside the Rijksmuseum. The Rijksmuseum, as stunningly restored as you might hope – as, indeed, it should be after 10 years and £500m. It’s huge, and might be described in British terms as the V&A and National Gallery rolled into one – except it’s nearly all Dutch, bringing home just how rich their history is. Oddly, in that context, the vista on approaching is dominated currently by the biggest sculptures of John Chamberlain and Henry Moore.

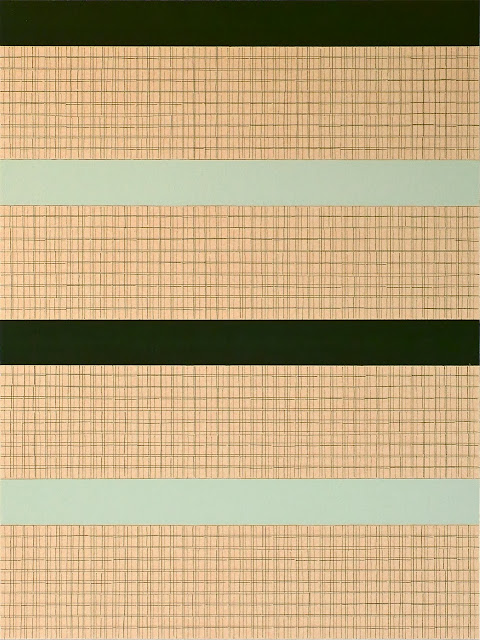

Lucy McKenzie: Something they have to live with (detail)

Lucy McKenzie: Something they have to live with (detail) · The Stedelijk Museum, which spans the modern and contemporary. I caught the openings of major shows by Paulina Olowska (on the ground floor) and ) Laurence Weiner (in an impressive new subterranean space) on the first anniversary of its reopening. Upstairs – by coincidence? – there was already a major show by Olowska’s friend Lucy McKenzie. Their double take on the interfaces between modernism and other cultures made for a rich pairing (Olowska with Malevich, Communist neons, Polish knitting designs and French street art in the max; MacKenzie with the Alhambra’s patterning, Glasgow bedsits and an interior by Adolf Loos).

Outside the Van Gogh Museum · The Van Gogh Museum, the last to reboot, opening in May 2013. The new display tells Vincent’s familiar chronological story through the lens of a concentration on his working methods, which has the advantage of emphasising the effort behind the genius which is so obvious to any reader of his letters, but not always part of the popular image.

Outside the Van Gogh Museum · The Van Gogh Museum, the last to reboot, opening in May 2013. The new display tells Vincent’s familiar chronological story through the lens of a concentration on his working methods, which has the advantage of emphasising the effort behind the genius which is so obvious to any reader of his letters, but not always part of the popular image.

Recreation of the extensive collection room, the spending on which was one factor in Rembrandt’s bankruptcy · The Rembrandt House Museum, which looks nothing like it did 350 years ago from outside and has almost no original content inside (due partly to its all being auctioned when Rembrandt was made bankrupt in 1656), but which does nonetheless provides a persuasive account of his daily life.

Recreation of the extensive collection room, the spending on which was one factor in Rembrandt’s bankruptcy · The Rembrandt House Museum, which looks nothing like it did 350 years ago from outside and has almost no original content inside (due partly to its all being auctioned when Rembrandt was made bankrupt in 1656), but which does nonetheless provides a persuasive account of his daily life.

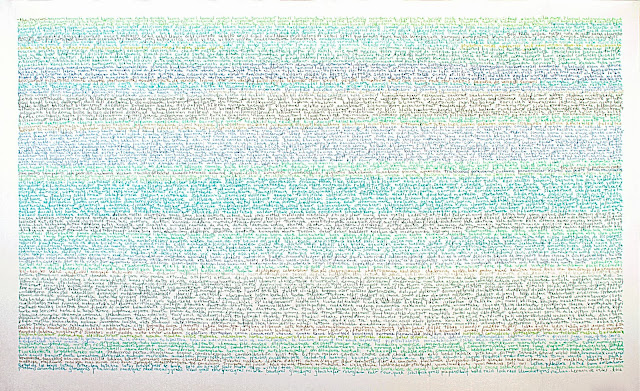

Alexander Gorlizki: Looking Out Looking In, 2013 at Galerie Martin Kudlek, Cologne in Amsterdam Drawing · The second edition of the work on paper fair Amsterdam Drawing, held at the NDSM Wharf on the northern part of the city with 40 galleries – mostly Dutch – each given a 15 meter run of wall space in varying formations. It was, appropriate to its medium, pleasurably intimate. If there was a trend here, it was perhaps away from minutely realised detail and towards broader effects, in both figurative and abstract work. Plenty of the latter might be termed ‘rough minimalism’, in which a casual approach is applied to geometry. An exception were the work of small-scale works of New York based Briton Alexander Gorlizki, which look like collages but turn out to be fully hand-painted – by the artists who work for him in India.

Alexander Gorlizki: Looking Out Looking In, 2013 at Galerie Martin Kudlek, Cologne in Amsterdam Drawing · The second edition of the work on paper fair Amsterdam Drawing, held at the NDSM Wharf on the northern part of the city with 40 galleries – mostly Dutch – each given a 15 meter run of wall space in varying formations. It was, appropriate to its medium, pleasurably intimate. If there was a trend here, it was perhaps away from minutely realised detail and towards broader effects, in both figurative and abstract work. Plenty of the latter might be termed ‘rough minimalism’, in which a casual approach is applied to geometry. An exception were the work of small-scale works of New York based Briton Alexander Gorlizki, which look like collages but turn out to be fully hand-painted – by the artists who work for him in India.

It’s no surprise that Piet Mondrian remains influential: you could see dancers cavorting with animated versions of his grids at Der Appel as well as plenty of related work at the Drawing Fair. German artist Frank Badur has for many years been utilising and undermining the grid, traditionally a starting point in eliminating subjectivity, as a site to be subtly infected with personality. He contrasts rigorously regular sections with sensitively humanised irregularities.

Pius Fox: Untitled, 2012 at Patrick Heide, London in Amsterdam Drawing

Rembrandt van Rijn: Three Crosses, State IV, 1660 in the Rembrandt’s House Museum

Rembrandt’s mastery of dramatic darks was shown at its most concentrated in the etchings at his house. These included the blackest stage of the various printings of Three Crosses, made years after he signed the third state. This state erases subsidiary characters through extended shadows, score dramatic curtains into the sky and hides one of the thieves – suitably enough, as it illustrates the moment of Christ’s death, when ‘there was darkness over the whole land’ (Mark 15:33).

Levi van Veluw: The Collapse of Confusion at Galerie Ron Mandos

Something of that atmosphere fed into the latest installations and charcoal drawings by Levi van Veluw. The latter are a recent development, but are of a piece, being derived from his plans for installations. Having previously established his own language of obsessive order featuring thousands of square bricks, van Veluw turns to darkness and disorder in both media in his new show, in which desks collapse and cupboards fall as if returning to molecular origins. The results are gloweringly atmospheric.

Paul Klemann has been painting his dreams for forty years, taking the process far enough that – although he spends ten hours a day in bed – he sets his alarm clock several times a night in order to scribble notes. The results often bring a child-like freshness to what might be seen as decidedly adult obsessions: the examples at the fair included a dish of penises being seasoned with salt as well as what looked like a rather touching scene between snow people. Are they people, then, or statues? And surely children might be looking on…

Karel Appel: Questioning Children 2, 1949 at the Stedelijk Museum

That childlike quality could also have been traced back to the CoBrA movement, which is well-represented in the Stedelijk. Karel Appel is the best-known representative of the ‘A’ in Copenhagen-Brussels-Amsterdam (he was a founder in 1948, along with Constant, Corneille, Christian Dotremont, Asger Jorn and Joseph Noiret. Questioning Children 2 itself undercuts the childlike spontaneity by its origin in Appel seeing children begging in post-war Germany. If it looks familiar, by the way, that could be because the first version of Questioning Children is in Tate Modern.

Vous Etes Ici, whose directors started Amsterdam Drawing in 2012, have recently moved to big space near the fair’s site. Kansas watercolourist Charlie Roberts tends to depict manic collectives, but his engaging recent series of parties of masks-come-houses is comparatively orderly and doesn’t seem to have much of Appel’s hidden angst, but who knows?

Vincent van Gogh: The Courtesan, 1887 at the Van Gogh Museum

Van Gogh was, of course, strongly influenced by the Japanese art: he collected hundreds of prints, made several painted versions and fed its inventive perspective, dramatic cropping, strong diagonals and blocks of plain colour without shadows into his own style. Van Gogh added his own border to this copy of Eisen’s courtesan. It’s a combination of typical motifs from Japanese art which amplifies the central subject by reference to French slang of the time: a ‘crane’ being a prostitute, and a ‘frog pool’ a brothel.

It wouldn’t be hard to speculate that the Japanese influence runs the other way in Yoko Murata’s paintings of animals and landscapes: there’s a freshness and passion to her paintwork. The results, as in this ghost of a mouse, aren’t quite sweet: as she herself says, we cannot understand what animals are really thinking so however much we cherish them, they may bite us, and ‘to people who think ‘Oh, how cute’, I want to say ‘You’re being fooled by my animals!’

Erik van Lieshout: Ego, 2013 – installation of 9 drawings at Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam in Amsterdam Drawing

herman de vries: The Saviours at Art Affairs, Amsterdam in Amsterdam Drawing

Images courtesy of the relevant galleries and artists. Trip courtesy www.holland.com , www.artsholland.com and the Movenpick Hotel, Amsterdam