Here’s a handsome new volume, well-illustrated, but more social history than art book, which tells of the emergence of London as an international art scene, during the years that followed World War II. Its subtitle is Art and Culture in the 1960s. Its weakness, if it has one, is that it doesn’t attempt to answer a major question: ‘What happened after that?’. The 1960s was now more than half a century ago.

The boom in British art did not last. By the late 1960s, the impetus that had briefly sustained the British economy began to peter out – ELS

Before the war, Paris had been the long-established centre of activity for contemporary art, a tradition established by the rise of the Impressionist Movement in the 1870s. After the conflict ended, many British intellectuals and opinion-formers and at least some leading artists expected that this would go on being the case. There was, however, an increasing feeling post-war that Britain should promote its own contribution to the Modern Movement, and London’s New Scene documents this.

The impulse was fuelled by a number of things – first by increased cultural self-confidence because Britain has been one of the victors in the global conflict. Secondly, because the major market for new and experimental art was increasingly to be found, not in Europe, but in the United States, to which Britain was linked not only by a common war effort but by a common language. Also, in addition, by the rise of Pop culture, which though associated indissolubly with America, had some of its earliest beginnings in Britain. These developments are described in the first main section of the book, Pop Goes the Easel, which takes its title from the 1962 film directed by Ken Russell, shown on BBC TV. The four artists featured were Peter Blake, Peter Phillips, Derek Boshier and the short-lived and now largely forgotten Pauline Boty.

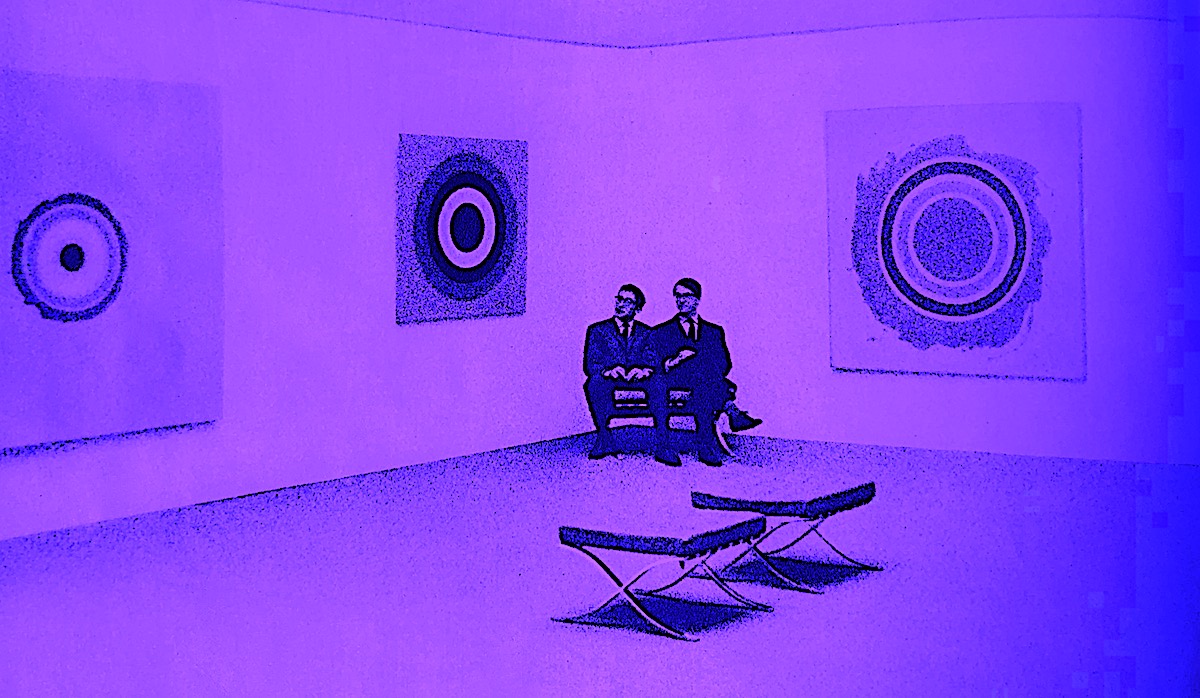

The next section is devoted to the Kasmin Gallery, the most important private gallery of the time, with additional information about the rival, but less successful, Robert Fraser Gallery. It is worth noting that both of these galleries had aristocratic support. Kasmin’s partner was the Marquess of Dufferin and Ava. Robert Fraser was the son of Sir Lionel Fraser, a banker who was a trustee of the Tate. While both galleries supported and promoted British artists, both were also closely linked to the new scene in New York and presented American artists in London. In fact, this was a very necessary part of their business. The British scene did not have enough major buyers to support a flourishing market in new experimental art on its own. Dealers such as Kasmin and Fraser relied for their success on attracting an international spectrum of collectors, attracted to London by its new reputation as a ‘happening’ city.

Though Kasmin was David Hockney’s dealer from the very beginning of his career, the main orientation of his gallery was not Pop. A far more typical artist, amongst those whom it represented, was Anthony Caro. Visiting the gallery, one got the impression that Caro and his American equivalents were taken much more seriously as artists by those in charge.

The boom in British art did not last. By the late 1960s, the impetus that had briefly sustained the British economy began to peter out. The book duly chronicles this, first in a chapter called Export Britain, which describes official and semi-official attempts to export British culture abroad, with crucial hesitations between what was ‘heritage’ (British heritage was safely popular in the United States) and what was genuinely representative of Britain in the then-present moment. This is followed by a chapter entitled Art School Revolution, which describes the revolution in training and governance that took place in British art schools at the end of the decade. It focuses on the sit-in at Hornsey, which, as the author of the book, Lisa Tickner, rightly says, ‘deserves attention as one of the more sustained attempts to question the social values and political import of art, design art art-education at the end of the decade.’ It was only partly successful, but this and similar efforts demolished the British art world that had known a major degree in international success in the 1960s. From the end of the decade, it became increasingly difficult to list that art world’s defining national characteristics.

In the 1970s and 1980s, there was an art world that, at its most extreme, here in Britain and elsewhere, could define a work of art as being, if the artist so chose, simply a statement made in words – no element of craft required. In addition to the cult of Conceptual Art, there was also Destruction in Art, as exemplified for example by the work of Gustav Metzger. The British YBA Movement in the 1990s achieved a moment of popular success, but today it has few survivors with significant international reputations. The contemporary British art world is both populist and internationalist, with a cult of artists from minority communities, plus in addition a strong element of self-righteous moralism. Apart from this last, it has little to define it as being specifically British. It competes with a number of different art worlds elsewhere – Russian, Chinese, Japanese, Indian, Iranian, Central Asian, Latin American, Middle Eastern, African – most of which are much more clearly defined culturally than itself.

Top Photo: Kasmin Gallery – John Kasmin with gallery partner Lord Dufferin – Kenneth Noland Exhibition c1965

Lisa Tickner, London’s New Scene – Art and Culture in the 1960s, The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, Yale Books