1989 was ‘Museums Year’ in the United Kingdom, a celebration of our cultural institutions which inspired Lubaina Himid to make a body of work that was displayed at Chisenhale Gallery in London in the summer of that year.

Her installation, ‘The Ballad of the Wing’, included six large paintings, four smaller paintings, a series of sculptural arrangements on high plinths and a video work titled Sphinx by the Scottish-Ghanian artist Maud Sulter. Himid presented the work as a touring exhibition of ‘The Wing Museum’, a fictional collection commemorating Black creativity and resistance, while also marking the continued erasure of Black presence across sport, industry and culture. For Himid, ‘The Wing Museum’ was a concept that was not ‘about oppression’ but invited care for precarious stories and the acknowledgement of ‘Black creativity in everyday life’.

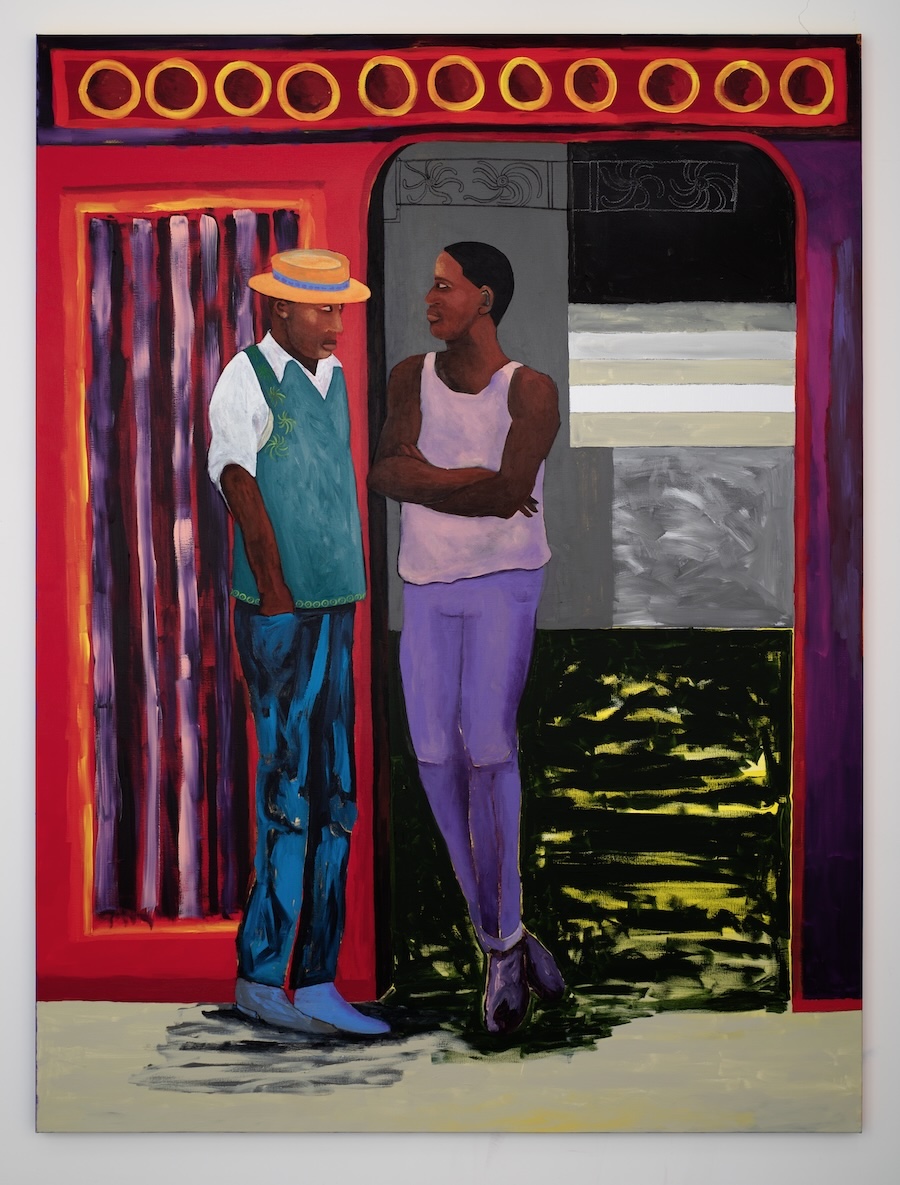

Lubaina Himid, ‘Try Out A Few Of Them’, from the series ‘How May I Help You?’, 2024

Her practice as an artist-archivist of forgotten stories is also what is primarily celebrated in ‘Another Chance Encounter’, an exhibition which includes collaborations with Magda Stawarska. It was a maxim of Kettle’s Yard founders, Jim and Helen Ede, that art could be enjoyed ‘at home unhampered by the greater austerity of the museum or public art gallery.’ With this exhibition, Himid and Stawarska have been inspired by the architecture, careful placement of artworks, objects and textiles, and the everyday rhythms of the Kettle’s Yard house. Their new works respond to aspects of the Edes’ collection, their life locally and abroad, as well as aspects of Himid’s own work. In addition to use of the gallery and educational spaces, the exhibition includes several interventions in the house itself. These open up hidden spaces to reflect on obscured histories.

The French artist Henri Gaudier-Brzeska tragically died while fighting in the First World War, aged just 23, and his extensive artistic output ended up in the possession of the British Treasury. When the Tate refused to acquire it, Jim Ede bought Gaudier-Brzeska’s entire estate and zealously promoted the artist’s legacy for the rest of his life. As such, in 1931, he published the book ‘Savage Messiah’, based on the ardent correspondence between Gaudier-Brzeska and his companion, the Polish writer Sophie Gaudier-Brzeska. In these ways, Gaudier-Brzeska’s estate, including his art and archive, was foundational to what became the Kettle’s Yard collection.

Himid and Stawarska’s installation ‘Still Bitter’ is the latest in their nine-year creative dialogue. It takes its inspiration from letters exchanged between 1917 and 1918 by Sophie Gaudier-Brzeska and the English artist Nina Hamnett as they sought to secure the legacy of Gaudier-Brzeska after his death in 1915. Sophie was Henri’s committed life partner, while Nina was his friend, a favoured model and sometime lover. The letters trace the two women’s efforts to navigate their own complex relationship, and this is reflected in the title of the installation, which appears spelt phonetically in English and Polish across one of Stawarska’s prints. The title refers directly to the somewhat awkward tone of the surviving letters from Sophie to Nina, as well as to other feelings of discontent that might arise, for instance, from the long neglect of women artists and writers. In this installation, sour feelings are not shamefully covered over but acknowledged as an honest response to an unequal world.

Magda Stawarska and Lubaina Himid, Slightly Bitter (detail), 2025, mixed media installation. Courtesy Yamamoto Keiko Rochaix, London, Hollybush Gardens, London and Greene Naftali, New York.

With this installation, Himid and Stawarska elaborate on lives usually kept at the margins of the story of Kettle’s Yard and Modern Art more generally. However, while rooted in Gaudier-Brzeska and Hamnett’s correspondence, the installation also playfully expands on the established history. Using the motif of the postcard, Himid and Stawarska bring together images of key locations for Hamnett and the Gaudier-Brzeskas and reproductions of artworks, with fictions and fabrications, alongside their own personal correspondence and fragments drawn from their own lives and practices.

‘Slightly Bitter’ tangles Himid and Stawarska with Hamnett and Gaudier-Brzeska, showing how life, art and history can entwine and resonate. Stawarska’s sound work combined with her prints and paintings on paper and zinc encircles the gallery. Works by Himid, including a painted door and a series of small paintings on canvas that realise subjects described by Hamnett in her autobiographical writing, tentatively mend breaches in our knowledge and awareness.

Doors and openings are a key image throughout the exhibition, with Himid’s interventions in the house being hidden behind doors or in drawers, and Stawarska’s sound installation in the house being located in a small kitchen not usually open to public view. In the exhibition’s second gallery, Himid has installed a large set of doors that transform the gallery into another threshold space. This sequence of open and closed panels frames and blocks our view through the gallery window, and when seen from behind, the gallery space. Taken from a stately home, the doors now function like a barricade – both a means of protection and containment, depending on where we position ourselves. These barricades with openings are symptomatic of the way histories and archives can both inform and obscure.

Himid’s paintings in this gallery depict a series of encounters between shopkeepers and their customers. She views these paintings as depictions of shops in Tangier, Morocco, that the Edes may have passed by or frequented before they moved to Cambridge. Located at the threshold of one of these shops, each painting captures a moment of tense proximity between two figures whose relationships are ultimately unknown. Short scripts, written by the artist, accompany the paintings and heighten the tension by stating the difference between what is said and what is thought. These paintings ask us to think about our own place in relation to the spaces and figures within them, and further the sense of something being withheld that is an important theme of Himid’s recent work.

Her archive relating to ‘The Ballad of the Wing’ also negotiates the possibilities of representation and artistic skill with ethical questions around awareness, recognition and exposure. This display revives ‘The Ballad of the Wing’ through reproductions of the existing large paintings, as well as Himid’s writing, Sulter’s ballad, written for the installation, and materials gathered from numerous archives and collections.

For this installation, Himid imagined the wing as a symbol of strength and freedom. She wrote an origin myth, in which we learn that the wing records’ victories and injustices’ and serves as a protector for Black life and creativity, extending the rich culture of the African continent across the world. Similarly, Sulter’s ballad, which has ‘stories to be told’, speaks of ‘times when the wing’s been there to witness for us.’ Their work here responds to the history of colonialism in Africa, enslavement across the Atlantic and Indian Oceans and acts of resistance against these conditions, connecting the disenfranchisement of enslavement and colonialism with the destruction of cultural memory.

Two of Himid’s paintings from the original ‘The Ballad of the Wing’ installation, ‘Sour Grapes’ and ‘In Spinster Salt’s Collection’, can be viewed in The Women’s Art Collection at nearby Murray Edwards’ College. The latest exhibition there, ‘Looking at Her’, explores portraiture and how artists turn to the figurative and the fictitious in their expansive depictions of women. There are synergies with ‘Another Chance Encounter’ and the two are worth viewing together. ‘Another Chance Encounter’ also extends beyond Kettle’s Yard, with a display of five curtains based on never-before-seen paintings by Himid which are installed at the Meadows Community Centre.

As a result, there is a plenitude, as well as a plurality, to this exhibition which has many disparate strands linked by an archival search for untold stories and obscured histories.

‘Lubaina Himid with Magda Stawarska: Another Chance Encounter’, 12 July – 2 November 2025, Kettle’s Yard –

Visit Here

‘Looking at Her’, 3 May – 7 September 2025, Murray Edwards College –

Visit Here