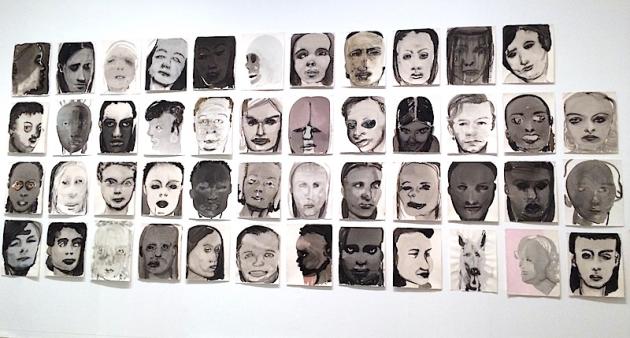

On entering the Marlene Dumas exhibition at Tate Modern and being faced with the Rejects series (1995-2014) of ink and graphite portraits, you are immediately struck by a sense of the origins of the shows impactful title; ‘The Image as Burden’. Imposing and striking, this series is comprised of works discarded from another of Dumas’ projects.

The decision to place these works at the very beginning of the viewers’ journey around the exhibition for me provides an insight, through the curating, as to where the priorities of Dumas’ practice may lie.

In exposing her ‘rejects’, Dumas is honest about her own very human capacity to judge, acted out through her artistic process here and potentially mirroring something of societies standards and norms. Yet in her decision to tell of the ‘rejects’ story regardless, she exposes that which for me makes up the very fabric of the power of her artwork; the privileging of the overlooked or taboo in much of human experience.

In exploring issues of love, life, death, sex and shame Dumas, maybe surprisingly at first glance, does not paint from life and instead uses found images to lead her explorations.

“I want to give more attention to what the painting does to the image, not only to what the image does to the painting”

There is something in the reciprocal nature of this described process that feels very relevant to the viewers’ ability to become enmeshed and immersed in the intense qualities of Dumas’ portraits.

Her works exude a paradoxically beautiful yet ugly sense of humanity in their ability to be both awash and surfaced, yet unending and eternal.

In room 7 an intriguing juxtaposition can be found in the work entitled Great Britain (195-97). The pairing of portraits of both supermodel Naomi Campbell and Diana Princess of Wales create an interchange of expression exploring notions of social constructions such as femininity, class and race.

A progression of the ‘Magdalenas’ series of works, referring to the biblical, penitent ‘fallen woman’ Mary Magdalene, Great Britain along with works from the Magdalenas series for me contain uncomfortable truths in their consideration of art and femininity spanning time and variant cultures. Clues to source material and references to historical art figures can be found in the works subtitles and evidence in the works, that which otherwise is without context.

In 2000 Dumas made a notable move towards the depiction of images of war in her practice. In room 11 the disturbingly moving piece the Woman of Algiers (2001) is an arresting testament to this direction. The depiction of a women held captive by the French during the Algerian War of Independence is a palpably painful representation of the potential location of the personal in the political. When the original source photograph is revisited by Dumas in the piece The Trophy (2013), seen in room 14, the impact of the use and depiction of women’s bodies and how they are portrayed and effected during times of conflict, comes all the more sharply into focus.

The parallel that can be found in Dumas’ continual exploration of the power of the image in the wider social and political context along with the very intimate and often personal depictions of people, guided by her own moments of turmoil, creates a complex and insightful representation of humanity and its many facets.

In viewing Dumas’s works in the flesh I was struck endlessly by the idea, that that which is beautifully or monstrously human, that which makes us wholly human, is in actuality completely transient and ephemeral. This sense, which for me feels just out of reach, is so richly encapsulated in Dumas’ marks, or lack there of.

Words/Photo: Corrina Eastwood © Artlyst 2015