Painting has been declared dead many times as it has reeled under the double-barrelled attack of photography and conceptual art. Similarly, figurative art has at points been counted out in opposition to abstraction and art for art’s sake. Nevertheless, both have survived, enabling us to have our cake and eat it in an art world where conceptual art, digital art, installation art, painting (including figuration and abstraction), performance art, photography, sculpture, and video art all co-exist and interact.

“Kitaj was determined to pursue figurative painting, whether it was in or out of fashion in critical circles”

Two artists whose dogged persistence with figurative art, in the face of more reductive critical perceptions of art, enabled us to reach this place of diversity are currently having major retrospectives in London: Philip Guston and R.B. Kitaj. The work of both these Jewish artists remains controversial. Guston’s retrospective was delayed because of concerns regarding his Ku Klux Klan imagery despite there being a powerful message of social and racial justice at the heart of his work, while responses to Kitaj’s work continue to reflect the “Tate War” of personal attacks from critics from which the artist and his reputation have never fully recovered.

Both artists moved in influential circles, with the novelist Philip Roth – who “rebelled against the practice of Judaism” and “the implicit communal demand that he abide by its historic practices” – being a shared contact and friend. Kitaj “drew memorable portraits of the novelist and was, at least in part, the model for Mickey Sabbath, the raucous protagonist of ‘Sabbath’s Theater’ (1995)”. Guston was the writer’s near neighbour in Woodstock, New York; “so close were the two Philips in the early ’70s that Guston, then at something of a low point in his career, began to make caustic drawings inspired by ‘Our Gang’ (1971), Roth’s absurdist satire of the Nixon administration”. Roth’s themes of age, sex, mortality, anti-Semitism, Jewish identity and experience, and the blurred boundaries between autobiography and invention, real life and fiction, are ones that also find echoes in the work of Guston and Kitaj.

Largely self-taught, Guston was drawn to cartoon imagery, European Old Masters painting, surrealism, and Mexican muralism, with his early figurative work becoming increasingly political. Following a first trip to Italy, he moved towards an increasingly abstract language, becoming an influential figure in the New York School alongside his high school friend Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko. Then, from the late 1960s onwards, Guston became disillusioned with abstraction as he contended with the increasingly troubled world around him and began to wrestle figuratively with the concept of evil in his practice.

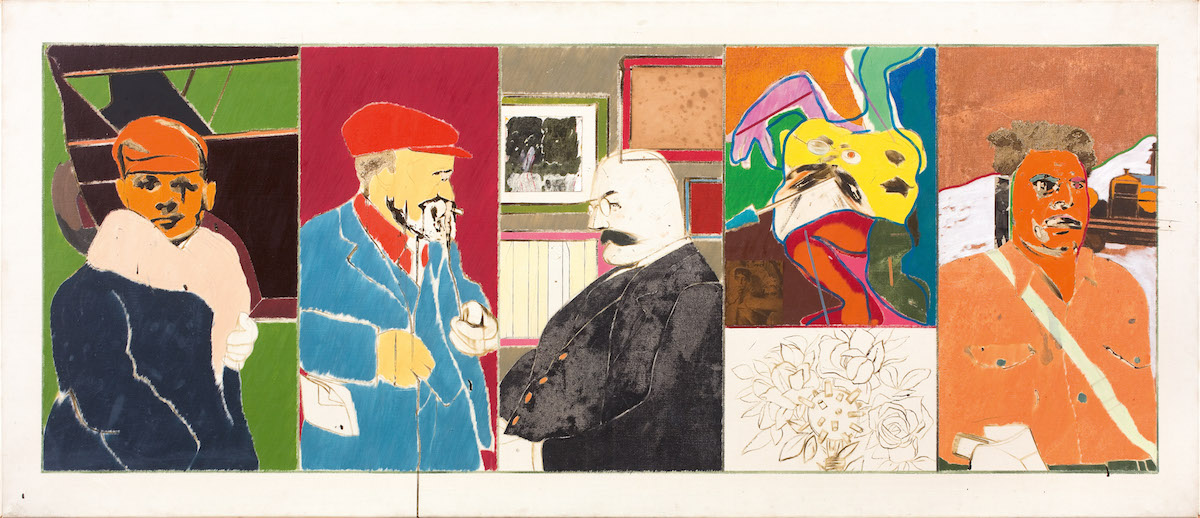

Right panel inscribed lower left ‘General of hot desire’, Oil on canvas (diptych)

Kitaj, by contrast, from his Pop Art collage beginnings to his final Los Angeles paintings, was resolutely figurative. He was determined to pursue figurative painting, whether it was in or out of fashion in critical circles, with a dedication to the human figure, art history and the great painters from Giotto to Cézanne. At the centre of a peer group that included David Hockney, Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff, which came to help define a new generation of artists from the 1960s, his friends and peers were also his subjects. Among other examples, Kitaj’s drawing of Hockney, ‘D.H in Hollywood’ (1971), is exhibited in public here for the very first time.

Kitaj was a collagist throughout his career, whether literally collaging together disparate materials from newspapers and magazines, as with key early works such as ‘Nat Lib’ (1962) or ‘The Republic of the Southern Cross’ (1965), or bringing disparate imagery together in paint on canvas, as with ‘Synchromy with F.B. – General of Hot Desire’ (1968-69) or ‘Fulham Road, Cinema Bathers’ (1988). Collagists visually harmonise disparate images in such a way that, in looking at the completed work, we are aware of both disjunction and connection. This combination contributes to the liveliness of Kitaj’s images, where interest arises as much from tensions created by disjuncts as from the connections that are also being made. Meaning courses through his pictures and their iconography that uses source material taken from life, film and art, with each piece sewn into grand, luminous compositions. Alongside are wonderful drawings that are both more straightforward and realistic while also demonstrating Kitaj’s consummate skill as a draughtsperson; the critic Robert Hughes rightly proclaimed that “Kitaj draws better than almost anyone else alive”.

After a peripatetic lifestyle in his twenties, Kitaj settled in London in 1959 and remained a presence there for the next 38 years. Although he travelled widely, with extended trips to the US, France and Spain, much of his life – painting, drawing, socialising, book-buying – unfolded in London. At Marlborough’s New London Gallery in 1963, he held his first solo exhibition, which sold out. At the Hayward Gallery in 1976, he brought together a seminal group of paintings and drawings in ‘The Human Clay’, which became the canon of ‘a School of London’. And at the Bevis Marks Synagogue in the City of London, surrounded by his friends and colleagues Hockney, Lucien Freud, Auerbach and Kossoff, he married his beloved wife, artist Sandra Fisher, in 1983.

Jewish identity became a major theme and preoccupation of his work. His Diasporist art is the art of movement, change, migration, contradiction, dislocation and dissonance. Kitaj defined the Diasporist artist as living and painting in two or more societies at once and wrote two manifestos on the phenomenon of creating paintings such as ‘The Gentile Conductor’ (1984-5), ‘Messiah (Boy)’ (1980-86) and ‘Besht Imaginary Portrait of the Baal Shem Tov’ (1987) which cleaved to his “own uncanny Jewish life of study, painting, unthinkable thoughts and near death …” He would often refer to himself as the “wandering jew”. He would commonly depict Jewish people on trains as part of the connection between the faith and the process of travel. In ‘The Gentile Conductor’, the red carpet of the train corridor corresponds to an account of a train journey to Auschwitz he read about, and in a work of a similar composition, Kitaj explained the conductor represented ‘darkness’.

In 1997, Kitaj left London for Los Angeles. Repatriation to the country of his birth prompted a creative revival in him. His work remained self-reflective and autobiographical, but as his life circumstances changed, so did his art. The untimely death of his wife in 1994 affected him profoundly and it was in Los Angeles that he reached for new iconography to express his grief and continuing love for her. At this time, Fisher took on the guise of an angel, literally being given wings in her bedside form in ‘Los Angeles No.16’ (2001) alongside Kitaj himself.

‘R.B. Kitaj: London to Los Angeles’ includes significant groups of paintings from every period in Kitaj’s career. As Matthew Travers, Director of Piano Nobile, has said, this exhibition enables us “to reassess an extraordinary body of work and introduce a new audience to Kitaj, who haven’t had the opportunity in recent years to see his career mapped out from the seminal ‘collagist’ works of the sixties through to the sun-drenched, Cézanne-inspired Los Angeles pictures.”

Ultimately, Kitaj explained his approach to figurative art in terms of Diasporism: “Diaspora is often inconsistent and tense; schismatic contradiction animates each day. To be consistent can mean the painter is settled and at home. All this begins to define the painting mode I call Diasporism. People are always saying the meanings in my pictures refuse to be fixed, to be settled, to be stable: that’s Diasporism …” As a result, many of the works displayed here – from his trail-blazing student days to the contemplative and grief-induced final years – are multilayered in their form and meaning. As works intended to provoke conversation, they require our eye to roam because of the difficulty in focusing on a single part of the image. When they were combined with written commentaries for his 1994 Tate retrospective (an approach inspired by the dialogical nature of Midrash), this provoked a furious reaction from some critics to that exhibition.

Guston’s work in a now infamous show of paintings with hooded figures at Marlborough Gallery in 1970, including ‘The Studio’ (1969), in which he interrogated himself as well as the establishment, provoked a similar critical response to that later given to Kitaj’s Tate retrospective. Critics and peers were dismayed with Guston’s new direction, interpreting the cartoonish figurative style of these ‘hoods’ as a crude rejection of abstraction.

While it may have been necessary, in the lifetime of Guston and Kitaj, to privilege or prioritise forms of art other than figurative art in order to break the original dominance of the figurative, figurative artists such as these two should be viewed as wounded heroes for persisting with figurative art and developing new expressions of it. The hits they took from critics did not prevent them from helping to lead us into the place of diversity we now inhabit, where the riches of all forms of art are apparent and where concepts such as the death of painting are redundant. For this, as much as for their considerable and significant bodies of work, they deserve to be celebrated.

‘Philip Guston’, Tate Modern, until 25 February 2024.

Read Sue Hubbard’s Review Here

‘R.B. Kitaj: London to Los Angeles’, Piano Nobile, until 26 January 2024.