With his Bob Dylan mop of curls and pug nose, he looks every inch the rebellious teenager that he was. The second youngest of ten children, three of whom died in infancy, Rembrandt was the son of a Protestant miller and a Catholic mother. Despite being sent to the Latin School in Leiden during his early years, he was soon chomping at the bit against formal education and was, at the age of 15 apprenticed, in 1621, to Van Swanenburg from whom he received intensive artistic training. Rembrandt would go on to become an innovator and a provocateur who’d turn the Dutch Golden Age of art upside down.

With a few scribbles and scrawls, he caught the tiny dramas of everyday life – Sue Hubbard

History painting was considered the highest form of art. The French theorist, André Félibien, claimed that the human form occupied the pinnacle of artistic endeavour because the painter reproduced ‘the most perfect work of God on earth and thus is God’s follower’. To capture the ‘passions of the soul’ was a painter’s greatest achievement. To this end, self-portraits were practised in front of mirrors. With his eighty or so works – drawings, etchings and paintings – Rembrandt held the title of the artist with the most self-portraits well into the 19th century.

This wonderful exhibition at the Rijksmuseum, held to mark the 350th anniversary of Rembrandt’s death, is part of a yearlong celebration. For the first time, they are showing all 22 paintings, 60 drawings and more than 300 of the finest examples of the Rembrandt’s prints in their collection. It explores different aspects of Rembrandt’s life and works through a variety of themes. The first section is predominantly made up of self-portraits. The second focuses on his surroundings and the people in his life: his mother, his wife Saskia as she lies ill and pregnant in bed, as well as beggars, buskers and vagrants that illustrate Rembrandt had an ability to depict poses and emotional states with great empathy. The last section demonstrates his gifts as a storyteller. Old Testament tales inspired paintings such as the exquisite Isaac and Rebecca, more commonly known as The Jewish Bridge c 1665-1669, a work of such consummate skill in its handling of paint and one imbued with such deep tenderness that it takes the breath away, even after countless viewings.

Walking into the first room of this exhibition, it’s easy to see why Rembrandt holds such appeal across the centuries. His acute observation is evident in the tiny etchings that depict him dressed in a fury cap holding down his rebellious curls, bending forward, shouting, frowning, and with a ‘broad nose’. By turns, he looks startled, wide-eyed and surprised. He seems to have possessed a substantial collection of headgear – caps, berets and even oriental headdresses – that he variously used as props. But these are no social portraits. Here is an artist who shows us what it means to be an individual. What it is that constitutes the idea of ‘self’. A self that was, during the Renaissance, being newly defined as uniquely human rather than the result of divine creation. And he made detailed drawings of animals. A lion, and a pig, possibly seen in an Amsterdam market, also show their unique individuality as sentient beings.

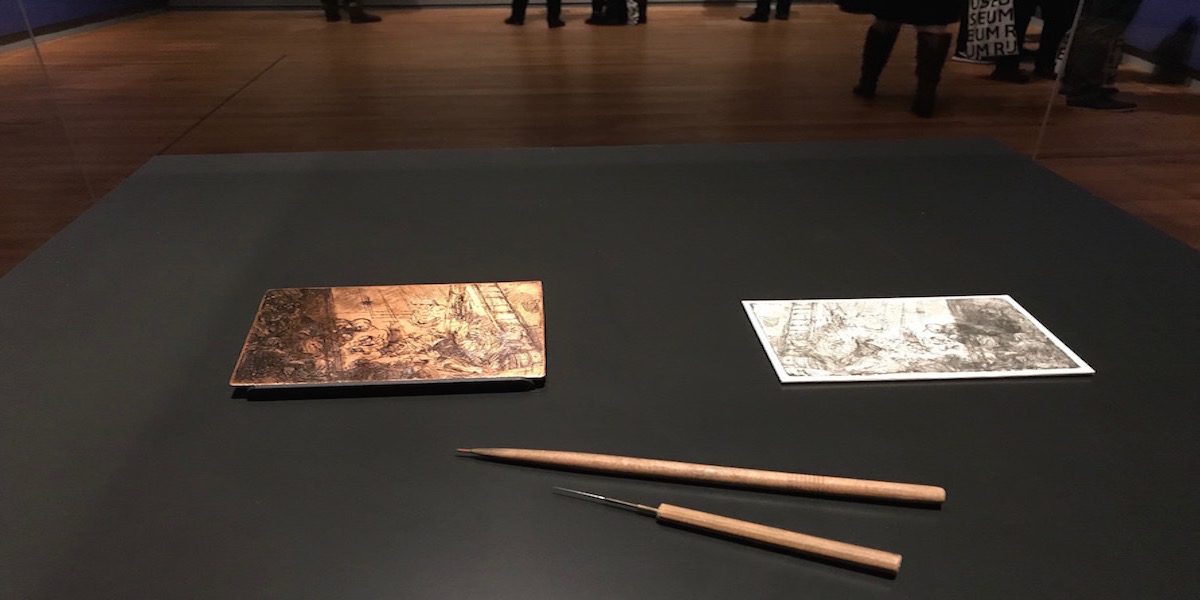

Above all Rembrandt was interested in people. Not stereotypes or ideas but real living flesh and blood characters. Salacious depictions were hardly unknown in the 17th century, but his etchings of a man and a woman pissing go beyond mere voyeurism into a form of social realism. His wife Saskia is shown in numerous poses. His fluid lines suggest that often he drew directly onto the copper etching plates. He’d cover the plate with a mixture of resin and beeswax, then draw through that surface with a needle to expose the metal. The plate would then be immersed in acid, inked and put through a printing press. One of the most touching is a small etching of his young son, Titus as a 15-year-old, executed in a bare minimum of lines. Titus’s shock of hair and pensive gaze are particularly compelling. Etchings rarely came into being in a single session. In the early years, when still gaining experience, he might begin with the head, move onto the torso and finally add the background. A master of light and dark, he used contrasts to add emotional depth and range.

From the beginning of his career, Rembrandt took on pupils for a fee. An essential part of their training was drawing lessons. Students drew from plaster casts and live models. Rembrandt often participated in these sessions and many of the drawings and etchings on show here originated this way and give a unique glimpse into the daily practices of his workshop.

The big draw of the Rijksmuseum is, of course, the Night Watch. Painted in 1642 it portrays, in almost cinemascope detail, Amsterdam’s ‘militiamen’, the city’s civic guard, which was commissioned for their guild headquarters, the Kloveniersdoelen. That he depicts the crowd in action was exceptional. Until then the subjects of group portraits were either shown standing or stiffly sitting side by side. Again, we see that Rembrandt is the master of light and shadow, which he uses to emphasise the captain’s hand gesture. Light also floods onto the small girl in a white dress standing, with a chicken hanging from her belt, in the central part of the painting. This was added, no doubt, as was the drummer on the right and the running boy on the left to convey immediacy, tension and drama.

To look at Rembrandt now, nearly 400 years after his death, is to be reminded of his keen observations, his vitality and realism. With a few scribbles and scrawls, he caught the tiny dramas of everyday life: a street woman making pancakes, a mother lifting the tunic of her small child so that he can pee in the canal. Technically astonishing in the way he conveys lace and cloth or portrays a landscape, his greatness lies not simply in these bravura skills but in the compassion, humour and truth that he shines on our frailties and vulnerabilities that show us, with deep tenderness, what it is to be human.

Words/Photos Sue Hubbard © Artlyst 2019

Sue Hubbard is an award-winning poet, freelance art critic and novelist. Her latest novel Rainsongs published by Duckworth is available here: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Rainsongs-Sue-Hubbard/dp/0715652850

“Hubbard deserves a place in the literary pantheon near Colm Toibin, Anne Enright and Sebastian Barry”. American Library Association

www.suehubbard.com