Sarah Bernhardt: Et la Femme Créa la Star, the summer show at the Petit Palais in Paris, reveals the private life and hidden talents of a woman who personified the rich, refined, romantic and sometimes decadent spirit of the Belle Epoque.

Born in 1844, Bernhardt earned global fame as an actress of mesmerising presence, emotional range and versatility, a flame-haired enchantress with a golden voice, adored by theatre lovers in fin-de-siècle Paris, London, New York and beyond.

Marking the centenary of her death in 1923, the Petit Palais show pays homage to that public persona, the theatrical Monstre Sacré as her friend Jean Cocteau called her, equally at home with Shakespeare, Rostand, Hugo or Racine, riveting as Hamlet or Lady Macbeth, Cleopatra or Pierrot the Clown.

Utilising 400 artworks and objects, the exhibition presents Bernhardt as far more: an accomplished sculptor and painter; a hard-driving theatre manager and impresario; an indomitable businesswoman who made, lost and remade fortunes; a liberated woman at home as a friend, often lover, and equal of the most famous and talented figures of artistic and literary society; an engaged activist and feminist ahead of her time; an extrovert eccentric who travelled between engagements in a private train with a menagerie of exotic pets; a sufferer from ill-health and insomnia who kept a coffin in her bedroom and had herself photographed sleeping in it. Memento Mori, histrionics, or a sharp eye for publicity?

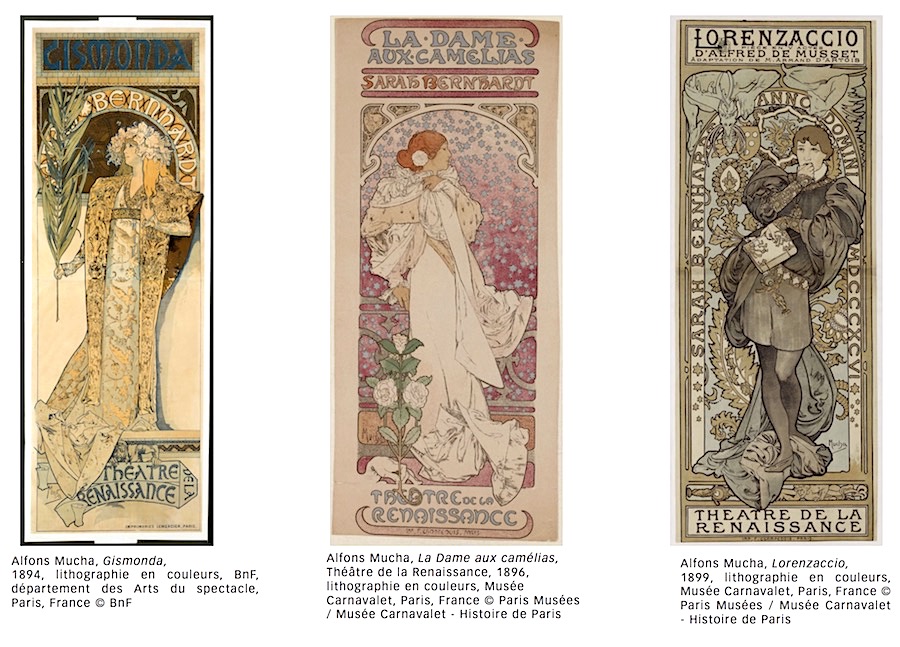

As a publicist, she was peerless, selling her image to advertise anything, from biscuits to face powder to “Terminus, the Absinthe that that’s good for you”. But above all, she was the poster girl of art nouveau. The exhibition brings together a visually stunning selection of Alphonse Mucha’s publicity portraits for her romantic heroine and cross-dressed hero roles – Gismonda, La Medée, La Dame aux Camellias, Tosca; de Musset’s Lorenzaccio and Shakespeare’s Prince of Denmark.

As if emerging from the posters are costumes to match; the queen’s crown from Hugo Ruy Blas, in silvered metal, tulle, pearls and strass; the Empress Theodora’s byzantine golden gown, embroidered in a silken thread and set with thousands of glass pearls; a jewelled bonnet, attributed to Lalique, in velvet, silver, opals, turquoise and amethysts: For students of stage design the show offers a masterclass in the costumier’s art.

Bernhardt did melodrama in spades in an age when “melodrama” was not a pejorative word. She was renowned for her stagy deathbed scenes in keeping with her private bedside coffin. Theatregoers loved them, but critics could take her with a pinch of salt. Among the sharper artworks in the show are caricatures by André Gill. Portraying Bernhardt as a hook-nosed sphinx or wispy-bodied Chimera, the fire-breathing snake-tailed female monster of Greek legend, they bear witness to her reputation for being, for all her success, what might now be called “a difficult woman.”

If she was difficult, her life wasn’t always easy, as the show’s excellent catalogue makes clear. Daughter of a Dutch prostitute, father’s identity uncertain: bundled off to a country nurse at birth and packed out of the way into a Versailles convent school for young ladies at nine. When she came out at 15, it was to go straight into her mother’s business: pregnant by an aristocratic “admirer” by the age of 19, mother of an illegitimate son two months after her 20th birthday.

When she played La Dame aux Camelias, she knew the part from the inside out, not just la vie galante but also the tuberculosis, which ran in her family. Her two younger sisters died of it, along with pain-induced drug addiction. Bernhardt lost a leg, amputated to end the pain of skeletal tuberculosis in 1915, which didn’t stop her from touring the trenches a year later as a troop entertainer in the long, bloody First World War battle for Verdun.

Another tribulation is referenced in several red-haired, hook-nosed caricatures prevalent at the time. Despite her convent education, Bernhardt was Jewish by birth, on her mother’s side. Despite her background, Bernhardt rose to the zenith of society within a French culture steeped in antisemitism. During the Dreyfus case years, she sided with Emile Zola in campaigning against the unjust punishment of a young Jewish army captain for spying crimes committed by a more senior Catholic officer. It was a stand that made her the target in a bitter legal, religious and political battle that split France into warring camps for over a decade, from 1894 to 1906.

In 1914 when she was named a Chevalier of the prestigious Légion d’Honneur for international services to the French language and for reinventing herself as a nurse and turning her theatre into a military hospital during the 1870 siege of Paris in the Franco-Prussian war. But years after her death, she became a target of further antisemitism. Her theatre was stripped of her name under the Nazi occupation of Paris in 1940.

Years later, the Theâtre de la Ville on Place Châtelet, closed since 2016 for a major renovation, is to get her name back again when it reopens on September 9 as the Theâtre Sarah Bernhardt.

Sarah Bernhardt: Et la Femme Créa la Star – Petit Palais runs until August 27: For lovers of theatre, visual arts and social history, the best show in town.