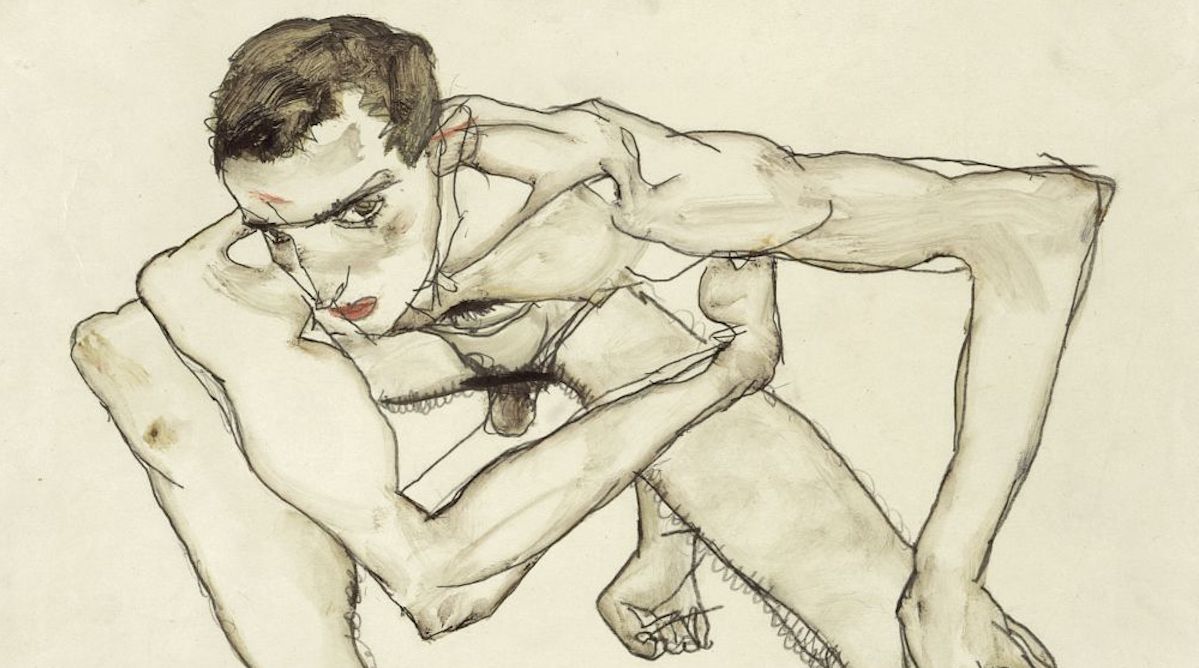

Tate Liverpool – There is a sense of the grotesque to the work of Egon Schiele. His gnarled and crooked drawings of nudes are strong but isolated within the pure space of the surrounding paper. Limbs become exaggerated and deformed as in ‘’Standing Male Nude’, 1910, watercolour, gouache, black chalk and graphite on paper, depicting the back of a man, his right arm elongated and almost robotic, monstrous and frightening. The skeletal figure captures your attention. Who is this man? Where is he from? What did he do? Why is his right hand so deformed? I imagine that he had interesting large hands and Schiele wanted to draw attention to them.

This contortion and expression of the human body is a fascinating angle within his work.

Schiele and Woodman were both Interested in their subject’s state of mind and not just the human physique

Schiele was born in Vienna in 1890. At the time Vienna was a creative community that included artists and thinkers such as Sigmund Freud, Gustav Mahler and Schiele’s mentor, Gustav Klimt. Innovative movements were emerging such as ‘The Vienna Secession’, set up by Egon Schiele, “a radical group of artists who had broken away from the traditionalism of the previous generation.”

Egon Schiele

Schiele’s Vienna was quite a conservative time, and his family were not drawn towards the arts. Schiele’s father died of syphilis when Schiele was young. Experiencing his father dying in this way later had an effect on the way he viewed relationships and sexuality in his art.

Schiele rejected what he felt was an old-fashioned approach to art at The Academy of Art in Vienna and instead sought advice from Gustav Klimt who became his mentor. Schiele became a master draftsman, creating many self-portraits including the nude and erotic drawings of women and himself, often depicting people in unconventional and exaggerated poses, with an emphasis on expressing hands. He paints the nude from many angles without inhibition.

The works by Schiele run alongside the intimate black and white photography of American artist, Francesca Woodman, born in Denver,1958. Woodman’s images of nudes and experimental self – portraiture melt with Schiele’s drawings throughout the exhibition. There are some interesting parallels taking place within their artworks.

Both artists were interested in expressing the human form clothed and nude from many different angles as well as expressing the character and person behind the nude and not just the figure itself. They both share a fascination with Space, Motion, Emotion and Expression, drawing and photographing the self or the model in motion or from unusual angles. Woodman, however, uses herself as her subject primarily throughout her work.

Francesca Woodman came from an artistic family (Mother Betty Woodman) who travelled extensively. In her teens, she travelled to Italy and in Rome she became interested in classical art, particularly the nude and “its status as a longstanding symbol in art history.” She received a camera from her father when she was 13. ‘Best known for her black and white photographs, her work often features the human body merging with its surroundings, becoming blurred due to movement during long exposure.”

Woodman uses the surrounding area to interact with her self-portraits as in her self-portrait of herself crouching beside a peeling wall, “Untitled, 1975-1980 and Self-Portrait at Thirteen (1972) which portrays herself turning her head away from the camera. Her face is covered completely by her hair and the space around her is composed of “fragmented elements, including a door, the underlit bench upon which she sits, and an empty chair.”

Francesca Woodman

‘Woodman often depicted herself as both subject and object in her work, addressing concepts of self, gender, body image and identity.’’ She went to Art school in Rode Island. This was a time where a lot of things were happening with photographing and documenting American society. She rented an old studio and took a series of photographs inspired by the Victorian era, Gothic literature and Romantic Bohemia. The studio was in a poor state but was the perfect backdrop for her haunting work. Woodman plays with the idea of appearance and disappearance and apparitional ghost-like figures. She shies away and hides from the camera as in works such as Untitled 1975-80, a photograph of herself nude in a room wearing stockings and hiding her face.

“Her work continues to be the subject of much critical acclaim and attention, years after she died by suicide at the age of 22, in 1981.”

The viewer has a right to express their feelings and opinion. It makes you aware of how criticism affects our opinions on art. However, it seems that most of art history would have to be obliterated if we cancelled out pictures of erotica or the nude. It makes you think also of how opinion changes over time. What is deemed as erotic art or offensive at some point may not seem the same way a century later. It is a difficult subject to strike the right balance and it would seem that there are certain types of erotic art that have become acceptable and some that do not still pass what is considered the moral guidelines. This is something that needs to be intelligently and very carefully considered in order to convey correctly the artists motives and/or the feelings of their subject. It is interesting to see the development of Schiele’s and Woodman’s works. Their works gradually change over time. Schiele’s Self-portrait ‘Head’, 1909, Gouache, watercolour and charcoal on paper. Demonstrates a clear departure from his early, more cautious style, placing an emphasis on the dark, troubled facial expression and experimenting with a white halo to separate the head from the blank page.

The exhibition shows how Shiel’s works start to become more troubled, more emaciated, erotic and later more bold and dynamic. There is a beautiful sense of line in Schiele’s works. His drawings of women are raw and sensual. His own self-portraits are sombre and “are strikingly raw and direct. He had a distinctive style using quick marks and sharp lines to portray the energy of his models.”

Woodman was preoccupied with art history. She focused immediately on herself and what could be crudely defined as “selfies”, however, she was not happy about the term “self-portrait” and saw herself primarily as a model in her own work. Using herself as the model was a matter of convenience as she was always available. Sometimes she faces the camera and sometimes she turns away as in some of her photographs taken such as El Series, Roma, May 1977 – August 78.

In Schiele’s work you observe the contorted positions, the bones and muscles as in his ‘Self Portrait in Crouching Position, 1913’. He would often position himself in front of the mirror, including depictions of himself and others in states of heightened emotion. “His quick lines reflect the animation and energy of his subjects. “This exhibition tracks both his evolving style in the early 1900s and his move towards colour.”

Schiele and Woodman were both Interested in their subject’s state of mind and not just the human physique. Woodman was interested in the spiritual aspect, the energy that the body contained, whereas Schiele had many models. One of his main models was a woman called Wally Neuzil. In 1912 they were stigmatised for being unmarried and having a relationship. They were evicted from their flat when he was found drawing a nude woman in his garden and at certain points in his career while seeking people to sit for him, he disregarded the age of his sitters and was jailed for a period of time for disregarding those moral boundaries.

Italy became a country that Woodman related to. The Renaissance was influential in her work. She enjoyed the work. She became fascinated by the work of Tintoretto in a church in Venice. She later worked on the angel series in Rome. The angel was this ephemeral figure, something spiritual and mythological something you can’t grasp. She was fascinated with this idea. Woodman’s interaction with mirrors and the glass frame was also a recurring theme in her work. She was trying subject and object a motif of her own work, referencing the myth of Narcissus and the idea of women being used as the muse throughout art history.

Schiele’s self-portraits also confront himself as a male model. After he dropped out of the fine art academy, his money was withdrawn by his uncle. Recognition was slow for him. His works were not bought so the dealer cut ties with him immediately. He married Edith who was from a respectable family but he stayed in touch with Wally although she eventually lost interest in their relationship.

The First World War starts to have an effect upon Schiele’s work. His works show expression in his hands as elongated and exaggerated. He looks stronger in his later works, but his hands are still tense and bony. He drew many studies before starting the paintings. His figures, unlike Woodman, were isolated from the surrounding space.

Woodman works in this intersection between photography and performance. In one photograph she has sellotape wrapped around her legs. Looking at movement and focusing for a while on women’s stockings and this idea of sticking, she and Schiele have this interest in fetishising in common.

In 1917 and 1918 Schiele is allowed to move back to Vienna. At this time he favoured black crayon to create more volume and create more rounded lines. His approach to composition separated his models from the background. He signs them at the bottom. He used a ladder to draw them from above and was interested in this spatial tension. He used colour to create this tension and advanced in his career. He becomes the leading artist in Vienna after Klimt. He organised The 49th exhibition of the Vienna Succession where he presented 50 works. The Spanish flue eventually killed his wife and Schiele himself who was only 28 when he passed away.

In the final series of Woodman’s works, we move towards larger works for her graduation show. Experimenting with other techniques. This motif of the swans, the idea of an ugly duckling to beautiful swan, this theme of resurrection interested her. She also did some video work on this performance, and you hear her own voice as she had committed suicide, 1981 at 22 years old.

She was extraordinarily productive, and in 1969 she moved to New York. She combined with making a living and being an artist. She sent her fashion portfolio but didn’t receive much work and merging her life with her art her depression began. She has left an extreme legacy. Cindy Sherman and many artists were inspired by her. She has had a huge impact on the visual culture and evolution of photography.

Woodman’s works are fascinating. I really enjoy her sense of movement and space and yet there is an intimacy in her work. In her photograph, Space2, Providence, Rhode Island, 1976 Silver Gelatin print she depicts herself partially crouching and the movement of her gesture creates a soft haunting almost gothic shadow in the room. There is this feeling of transience and time passing.

Like Schiele, there is also a sense of the grotesque and distortion. In her photograph, Space2, Providence, 1976 her posture is almost animal-like, her face hidden by her own hair, stagnant posture. Her images of clothes, her dresses and her standing with face covered, wearing stripy stockings could be a scene from a Schiele studio, a sense that their work crosses over in some way. She plays with light and dark beauty.

In her Untitled Providence, Rhode Island, 1975 -78 she shows a shaft of light across her lower part of her body. The texture of the floor, the decaying wall and purity of the light create a feeling of something spiritual.

Her photographs On Being an Angel, Rhide Island, 1976 are ethereal and intimate. There is a ghostly presence. Her photos of decaying interiors, a feeling that she is melting into the wallpaper or emerging like a spirit, a feeling of reality versus the spiritual world. “Working at either end of the twentieth century, Woodman’s photographs help to refocus how we see the work of Schiele, highlighting how the latter’s practices and ideas continue to have relevance to contemporary art.”

Ten years on from Tate Liverpool’s acclaimed exhibition of Gustav Klimt, Tate Liverpool showcases the works of his radical protégé, Egon Schiele, on the 100th anniversary of his death alongside the sublime photography of Francesca Woodman. Having written quite a few art reviews in Liverpool, I remember seeing the Gustav Klimt exhibition at Tate Liverpool and being overwhelmed by the beauty and decorative elements of Klimt’s work. It is interesting to think that someone so different in style was Schiele’s mentor, another interesting facet of the diversity of art and its influence and how we perceive art. The Klimt exhibition was one of the first exhibitions I reviewed in Liverpool for Nerve magazine at the time. You can read my review of that exhibition by following this link. http://www.catalystmedia.org.uk/archive/issues/misc/reviews/gustav_klimt.php

The Life in Motion exhibition currently on at Tate Liverpool is an interesting insight into how art can connect and artists can have linking interests and ideas in common through different time periods. Do go and see this interesting and exploratory exhibition on the human figure.

Review by Alice Lenkiewicz

Life In Motion Egon Schiele/ Francesca Woodman Tate Liverpool until 23rd September 2018