The first major exhibition of Glyn Philpot R.A. (1884-1937) in almost 40 years is currently at Pallant House Gallery, while Tate Britain has the first major retrospective of Walter Sickert at Tate in over 60 years. The differences and similarities between these two artists whose careers overlapped are instructive.

Between them, these exhibitions open up the foci and tensions of British art

Sickert was a central figure of the British artistic avant-garde, as both a painter and a critic, being a founding member of the New English Art Club, formed as a French-influenced alternative to the more traditional Royal Academy (RA), and the leader of the Camden Town Group of artists who were influenced by Post-Impressionism. Philpot was a highly successful and sought-after portrait painter who also created a series of sumptuous figure paintings with rich glazes influenced by the Old Masters. Many of his images are homo-erotic by nature and are now embraced by a younger generation of the LGBTQ+ community. He was the youngest RA member when elected in 1923 but, ten years later, had a painting rejected by the RA, having made a style shift embracing modernism in the 1930s. Sickert was primarily influenced by Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, while Philpot was influenced by Matisse, Picasso and the German Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) artists.

Sickert’s reputation has benefited from the consistency of his engagement with the then avant-garde, while Philpot’s reputation has suffered from his mid-career change of horses, meaning that neither those who valued his traditional style nor those who valued his modernism have fully advocated for his work.

Unlike Philpot, most of Sickert’s portraits were not specially commissioned, although his sitters, like those of Philpot, were well-known personalities (including those from the popular culture of music halls), showing the extent of connections within cultural circles and high society both artists possessed. Sickert’s portraits depict a wide range of characters, from the emaciated figure of the artist Aubrey Beardsley and the glamorous singer Elizabeth Swinton to famous music hall performers such as Minnie Cunningham and Little Dot Hetherington. Philpot’s sitters included a veritable Who’s Who of British society, from glamorous duchesses and countesses, such as Loelia, Duchess of Westminster, whom he painted in 1930, to poets and writers including Siegfried Sassoon, painted during the First World War, and actors such as Glen Byam Shaw, who he painted as the character Laertes in Hamlet in 1934-5.

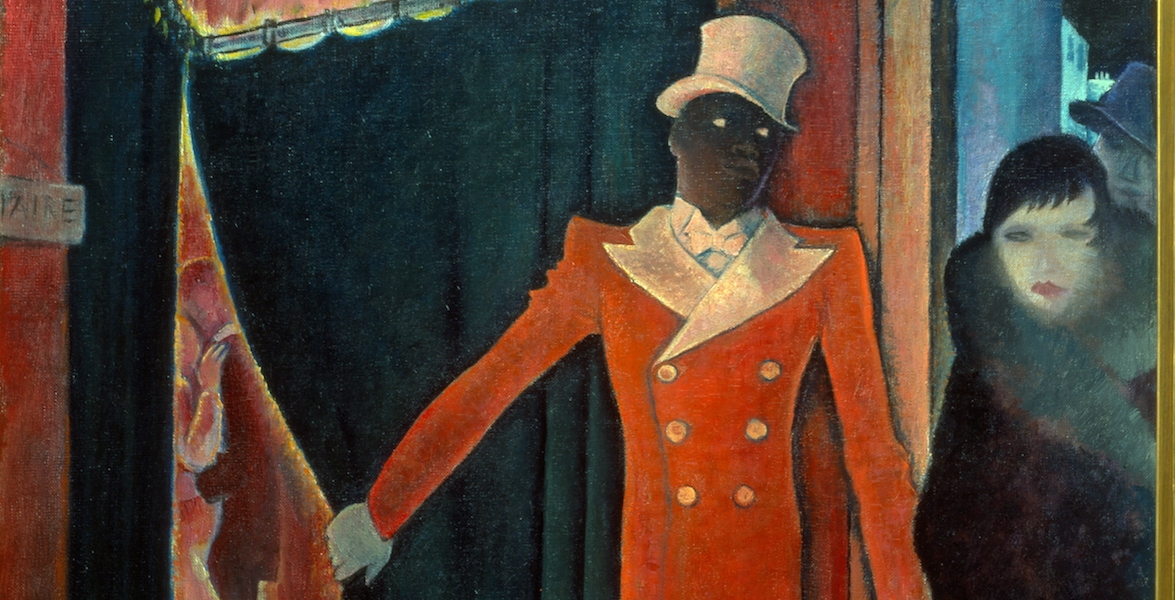

Sickert’s informal portraits are often closer to genre paintings than portraits, as he painted generic figures or ‘types’ of people in carefully observed and staged interiors. Sickert also created many self-portraits, while Philpot only produced one, intended as a one-off demonstration of his skills. Self-portraits were where Sickert engaged with the biblical or spiritual, depicting himself both as Lazarus and the Servant of Abraham. From 1912-13 onwards, Philpot gained a particular reputation for his sensitive representation in paintings, sculptures and drawings of unknown black sitters, including, in 1912-13, what is possibly the first recorded group of portraits of black subjects in Modern British art.

Both produced memorable and original subject pictures, exploring scenes from working-class life, the theatre and the circus, with Philpot also adding ambitiously unconventional treatments of classical and biblical themes. Sickert originally pursued a career in drama before turning to art and his interest in the stage was particularly reflected in one of his favourite artistic subjects: the music hall. Edgar Degas became a mentor to Sickert in 1885, following on in that role from James Whistler, with Sickert’s music hall images initially being inspired by Degas’ paintings of Parisian café-concerts.

Similarly, Simon Martin has noted Degas’ influences in some of Philpot’s key theatre-based works including The Dance of the Sugar-Plum Fairy, “an impressionistic depiction of the prima ballerina in the spotlight during the third movement of Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker pas de deux” which recalls Degas’ Dancer with a Bouquet of Flowers (Star of the Ballet) and The Little Dancer – exhibited at the RA in 1923 – where it seems highly likely that Philpot would have been “conscious of the parallels with Degas’ statue Little Dancer Aged Fourteen” found in the artist’s studio following his death and, from 1921, “cast in an edition of seventy-two bronzes dressed with a real fabric tutu.”

As his style changed, Philpot moved from depictions of ballet dancers or Shakespearian performers and productions to cabaret performers, nightclubs and the circus. His focus also included the audience and off-stage images. Resting Acrobats and Acrobats Waiting to Rehearse are among his greatest works revealing the behind the scene’s reality of staged performance in ways that also call into question the staging and image projection of his earlier swagger society portraits. Although those portraits made his reputation in his own day and time, the images that are now being re-evaluated and which will give him an enduring significance are images of those who were marginalised, faced discrimination, and whose images were rarely painted and exhibited at the time with the prominence and attention that was paid them by Philpot.

Sickert had a similar focus on subjects that were on the edge of those tackled by the mainstream art world of his day. This was apparent not just in his subject matter – dramatic images of performers and audiences, husbands and wives, prostitutes and clients evoking both the energy of working-class city nightlife and the claustrophobia of everyday existence – but also in the unusual and spectacular angles – the edge of vision through use of reflection and various framing devices – from which these scenes were captured.

Both exhibitions provide comprehensive overviews of their subject’s works; Walter Sickert primarily uses a thematic structure to do so, while Glyn Philpot: Flesh and Spirit’s aim is to combine the thematic with the chronological. As an exhibition enhancing one with an established reputation – albeit one that has faced questions about the dynamics of power depicted as well as those exercised by the depicter – Walter Sickert can include works by the influencers of Sickert – Whistler and Degas – and those influenced, including Lucien Freud. By contrast, Glyn Philpot: Flesh and Spirit seeks to rehabilitate and re-establish a reputation on different grounds from those on which his reputation was originally gained. As such, the focus is on Philpot’s work with a sense that the edginess of his work was what undermined his original reputation without gaining, either at the time or subsequently, the recognition it deserves.

Between them, these exhibitions provide and open up the foci and tensions of British art in a period when the traditional and the modern were, within British art, effectively counterbalanced. That balance was lost with Sickert’s reputation rising and Philpot’s, despite his effective embrace of modernism, falling. Interestingly, it is Philpot’s engagement with racial and sexual power dynamics which is playing a part in rehabilitating his work, while raising questions about aspects of Sickert’s work and reputation. Ultimately, these exhibitions open up a debate about the factors which influence the reception of work at particular points in time and the ways in which reputations can be gained, lost or called into question. We do not view the work of either or any artist objectively and these exhibitions not only show us great works that raise profound questions but also reveal how the works are themselves shaped and re-interpreted as a result of wider social trends and forces.

Words: Jonathan Evens ©Artlyst 2022

Walter Sickert, Tate Britain, until 18 September 2022

Glyn Philpot: Flesh and Spirit, Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, until 23 October 2022