The Rijksmuseum has devoted its south façade and auditorium to Steve McQueen’s Occupied City, an audacious and urgent work made all the more resonant against the backdrop of the ongoing Gaza conflict and the rise of the right in Europe and in the UK. Spanning thirty-four hours, this is cinema pushing far beyond conventional limits—less a film than a live immersion, a slow unravelling of Amsterdam’s layered history and unsettled presence.

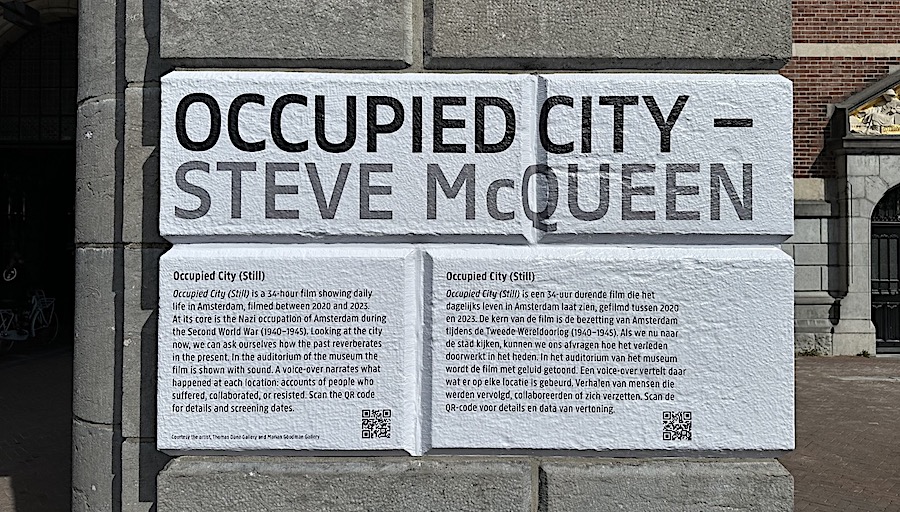

McQueen’s Occupied City was first completed in 2023 and is now given unprecedented scale in the Dutch capital. Two versions play out concurrently: a silent projection titled Occupied City (still), running continuously on the museum’s façade, and the full-length sound version screened in the auditorium during opening hours. Both are anchored in Bianca Stigter’s monumental book Atlas of an Occupied City. Amsterdam 1940–1945, which documents, address by address, the lives disrupted and destroyed by the Nazi occupation.

This is McQueen at his most expansive and his most uncompromising. Viewers are confronted not with a linear narrative but an accumulation of fragments: 2,000 addresses across the City, 2,000 traces of horror, absence, resistance and survival. The film does not ask to be consumed in one sitting—it cannot be. Instead, it seeps into the rhythm of the City itself, playing out as a counter-history that never quite ends.

The façade version strips the work of commentary, presenting an unbroken stream of images of contemporary Amsterdam, filmed between 2020 and 2023. We see masked faces in lockdown, climate marches, Black Lives Matter protests, people playing, waiting, protesting, or drifting through the City’s parks and streets. Silent, the images take on a spectral quality—every gesture appears haunted, every square heavy with memory. It is not spectacle but insistence: a reminder that life continues on ground still marked by atrocity.

The auditorium version layers these images with a dispassionate voice-over, recounting what took place at each address during the war. Deportations, betrayals, hunger, resistance, the sheer mechanics of occupation: each story lingers briefly before yielding to the next. The effect is devastating. The longer one stays, the more unbearable the weight becomes, until the act of walking out feels like a minor betrayal of its own.

Historian Bianca Stigter and Director Steve McQueen Occupied City Photo PC Robinson @ Artlyst 2025

McQueen has described Amsterdam as a city lived with ghosts, and Occupied City makes that metaphor literal. Time collapses. Pandemic-era footage and wartime testimony are not separated by decades but presented as parallel realities. The viewer is forced to hold both together: celebration and annihilation, survival and erasure, the banal and the catastrophic.

The presentation coincides with two anniversaries: Amsterdam’s 750th year and the 80th anniversary of liberation. That context matters. Museums thrive on commemorations, but McQueen resists the flattening that anniversaries often impose. He does not deliver a neat closure or a patriotic uplift. Instead, he pushes back against the idea that history can ever be neatly sealed away. His Amsterdam is always already occupied, always already marked.

Taco Dibbits, the Rijksmuseum’s director, has called this collaboration a long-cherished wish. It certainly places the institution on unusual ground. For a museum synonymous with Rembrandt and Vermeer, giving its façade to a 34-hour contemporary film is a striking gesture. However, McQueen’s project fits within the Rijksmuseum’s steady engagement with contemporary art, following Fiona Tan, Rineke Dijkstra, Anselm Kiefer and others. Unlike those exhibitions, however, Occupied City is inseparable from Amsterdam itself. It is not an artwork installed in a museum; it is a city-wide mirror.

Bianca Stigter’s Atlas provides the backbone, a forensic mapping of Nazi occupation down to the house number and even the floor. McQueen translates this into moving image, transforming archival knowledge into lived experience. Each story adds to a cumulative reckoning, but the film resists sentimentality. There is no swelling score, no climactic narrative arc. Its power lies precisely in its relentlessness: an insistence that the viewer cannot look away from what happened here.

The Rijksmuseum labels the façade projection as silent, but silence is never empty. Against the nightly traffic and chatter of Museumplein, the mute footage becomes uncanny. The ordinary—children skating, cyclists, lovers in parks—appears newly fragile, as if overexposed. We watch contemporary Amsterdam carrying on, yet know the ground beneath has been shaped by hunger, deportation, and resistance. McQueen turns silence into accusation.

The question inevitably arises: who will watch 34 hours of film? That may be the wrong measure. Occupied City is not built for conventional spectatorship. It is something to be entered and left, encountered in fragments, pieced together over time. Like the City itself, it cannot be consumed in full, only inhabited.

The work’s resonance is sharpened by its timing. The COVID-19 lockdowns and the rise of global protest movements are not presented as equivalents to wartime occupation, but as reminders of how fragile daily life can be, how quickly cities can be transformed by power, fear, or collective action. McQueen refuses to flatten history into analogy; instead, he insists on coexistence.

There is, of course, an institutional risk here. At 34 hours, Occupied City is not an easy ride, nor can it be absorbed into the quick churn of cultural tourism. However, the Rijksmuseum has given McQueen space, and the work benefits from it. It forces the museum’s visitors—many drawn to golden age paintings—to reckon with a darker, more recent layer of the City’s past.

McQueen has always been an artist of extremes, moving between Turner Prize installations and Oscar-winning features without compromise. Occupied City belongs to that lineage but expands it. It is monumental not in the sense of grandiosity, but in its endurance, its refusal to condense trauma into two hours of narrative closure.

The result is a film that demands your attention, to remember, to stay, to acknowledge. For some, it will be overwhelming. I myself had tears in my eyes when I left the auditorium after watching just two hours of this compelling account. For others, it is transformative. However, indifference is not an option.

With Occupied City, McQueen has created a vital record—he has made Amsterdam itself flicker, fracture and reveal its ghosts. At a moment when history is too often weaponised for political gain or reduced to tourist branding, he offers something more challenging, slower, and infinitely more necessary: an act of remembrance that refuses to end.

Words/Photos PC Robinson © Artlyst 2025