Surrealism: Beyond Borders presents an expansive and hugely varied retelling of the story of Surrealism that challenges the Paris-centric traditional art history tale of its flourishing. Movements move – it’s in the name – through change and development. Yet, the traditional telling of the story of modern art generally was only interested in moving on from one movement to the next, condemning past movements and their developments to the past and to obscurity. The argument was always that the beginning of a movement – any movement – represented its apogee and anything beyond that point represented decline and decay.

This exhibition gives the lie to that narrative and thereby suggests that the trick can and should be repeated with every other modern movement from Impressionism onwards. Certainly, the bulk of what is displayed here is entirely outside the usual telling of Surrealism’s story. Yet, the exhibition is packed to the gunnels with the characteristic mixed-up, merged, melted and morphing metaverse of Surrealism where out of control and beyond reason automatism are blended with the science of control and intent.

When, as here, a movement is explored beyond the narrowness of the initial spring – a revolutionary idea sparked in Paris around 1924 – that spring becomes a river in flood encompassing a much broader range of themes than was initially the case within the movement and, even, embracing what was originally considered its reverse, as here with the Catholic imagery of Hernando R. Ocampo or the blending of Sufism and Surrealism in Turkey.

The river of Surrealism, as displayed here, is particularly broad with over 150 works – ranging from painting and photography to sculpture and film, many of which have never been shown in the UK – spanning 60 years and 50 countries to show how Surrealism inspired and united artists around the globe, from centres as diverse as Buenos Aires, Cairo, Lisbon, Mexico City, Prague, Seoul and Tokyo. Grouped both by themes and geographical centres with archive materials from travellers who documented aspects of the movement and groups that sparked new mini movements within the whole, the exhibition, while overwhelming, is nevertheless endlessly fascinating and one to which many will choose to return.

While iconic images such as Max Ernst’s Two Children are Threatened by a Nightingale, Salvador Dalí’s Lobster Telephone and René Magritte’s train rushing from a fireplace in Time Transfixed are included, the real interest is to be found in the unfamiliar and less frequently exhibited works. Rarely seen works include photographs by Cecilia Porras and Enrique Grau, which defied the conservative social conventions of 1950s Colombia and those of Limb Eung-Sik and Jung Haechang from Korea. The desire for the body is a theme of photography in particular, with works by Hans Bellmer focusing on the female body contrasted with the photographs of French Surrealist Claude Cahun and Sri-Lankan-based artist Lionel Wendt. These are radical photographs exploring fluid identifications of gender and sexuality. Wendt’s intimate studies of nudes present queer desire outside of a Western context, while Cahun’s defiant performances of self-identity challenge fixed notions of gender.

Also rarely exhibited are the cadavre exquis (exquisite corpse) drawings that were clearly a feature of surrealist groups. These are made by one participant in the game drawing a form and, after folding or covering the paper so that only the ends can be seen, passing it on. A second person continues the work before again concealing it and passing it on. Along with examples by Frida Kahlo, Lucienne Bloch and André Breton, is Ted Joans’ Long Distance, an epic cadavre exquis drawing begun in 1976 and completed over 30 years later by means of 132 participants including Dorothea Tanning, Romare Bearden, Betye Saar and Malangatana Ngwenya. Long Distance extends – literally, being 9 metres long – the Surrealist idea of collaborative authorship to the people connected through Joans’ travels, linking artists located as far apart as Lagos and Toronto. Such group production fosters proximity and intimacy but also connects and makes visible diasporic and transnational communities.

Surrealism rejects oppressive rationalism by seeking to liberate the mind from outdated modes of thought and behaviour. As poet Urkhan Muyassar explained, the Surrealists sought to free the ‘mysterious moments’ of human creativity from a ‘superimposed’ reasoning to reach repressed thoughts, or ‘what lies behind reality. Surrealism aims to travel beyond reason and therefore contains a substantive body of work exploring spirituality, mysticism and religion in all their many and varied forms.

Kitawaki Noboru drew upon both the Taoist book of the I Ching and German author Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s book on the theory of colour to render visible the unseen laws of the universe. Malangatana Ngwenya’s allegorical depictions of daily life in Mozambique blend symbols and motifs drawn from local craft, Christianity, and the folklore of the Ronga. Hector Hyppolite draws on the religious syncretism of Haitian Vodou, which fuses traditional religions of West and Central Africa with Roman Catholicism to juxtapose the sacred and secular, the magical and the everyday. Hernando R. Ocampo merged his interest in Surrealism with overt religious imagery to explore the anxious environment produced by the shifting colonial influence of the US in the Philippines and the trauma of World War II. For others, like Kurt Seligmann, the search extended to magic and alchemy. The friendship between Remedios Varo and Leonora Carrington involved the study of Mexico’s Indigenous cultures and archaeological sites. Still, they were also influenced by occult and alchemical sources to infuse Surrealism with feminism, magic, and natural forces. Carrington’s Self-Portrait draws on her interests in alchemy, the tarot, and Celtic folklore, while Varo’s autobiographical triptych unites a dream image inspired by her friend Kati Horna with elements derived from alchemy, mysticism, and the occult. Varo’s triptych is being exhibited, as a whole, for the first time in 60 years, the three paintings having gone into separate collections following their original display.

These works – fascinating in their own right and profoundly absorbing when brought together – demonstrate that a deep dive into the spirituality of Surrealism would prove to be a revelatory exhibition, particularly when one also remembers the spiritual imagery and influences in the work of others included here, such Jean Arp, Joseph Cornell and Salvador Dalí.

Ladislav Zívr, who came to prominence in the Prague Surrealist collective Group 42, saw in his Incognito Heart an ‘emotional manifestation, intended to reveal the spiritual unknown inside us—to, in fact, discover us.’ That might just sum up the intent and impact of this expansive exhibition.

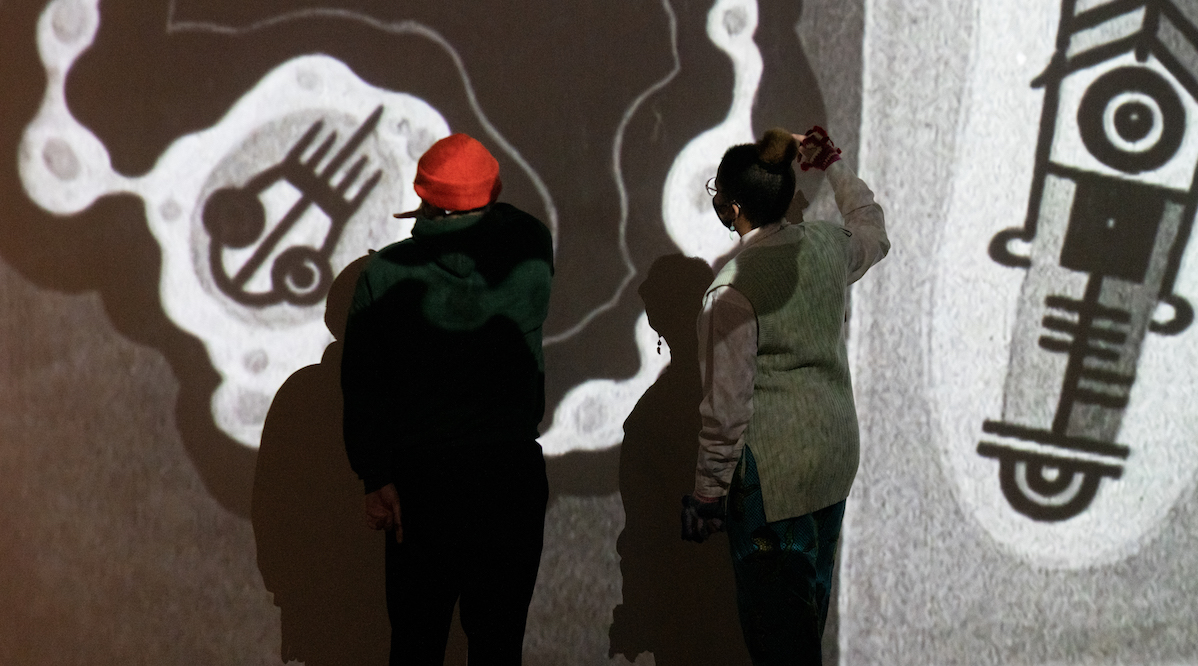

Top Photo: Photo @ Tate Sonal Bakrania

Surrealism Beyond Borders, Tate Modern, 24 February 2022 – 29 August 2022.

Read More

Visit