Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider, the focus of the current exhibition at Tate Modern, demonstrates the breadth of the group’s engagement in terms of transnational relationships, experimentation with form, colour, sound and performance, and a valuing of folk art. Apart from Impressionism, most early modern art movements had significant spiritual inspirations and motivations. Expressionism, whether that of The Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter) or The Bridge (Die Brücke), was no different and may have been one of the movements where spirituality was of the most influence.

The Blue Rider claimed that art knows no borders, and they sought to demonstrate the reality of that claim in Der Blaue Reiter Almanac, published in 1912. Yet, as the room specifically dedicated to images with a spiritual focus shows, their aesthetic concerns developed parallel with their belief in the deep spiritual significance of artistic experimentation, which drove their creative investigations.

Wassily Kandinsky’s interest in spirituality was explicitly expressed in his book On the Spiritual in Art, published in the same year as the Almanac. The book (an example of which is on display) communicated a vision for a new, “great spiritual” age, in which all art forms would coalesce as the “inner necessity” of artists – their inherent drive or will – would lead them towards spiritual expression. Many of Kandinsky’s observations about form, colour and spatial relationships, which appear purely aesthetic, derive from Thought-Forms, the theosophical classic by Annie Besant and C. W. Leadbeater translated into German in 1908. His attempt to express the spiritual in paint led him increasingly towards abstraction while drawing both on the ideas of Theosophy and the imagery of Russian Orthodoxy. Images such as ‘All Saints I’ and ‘Improvisation Deluge’ provide examples of this journey, as seen in his work.

Franz Marc’s background was in Christian theology, but he also became interested in Buddhism. This fuelled his engagement with animism—a belief in the latent spirituality of animals, objects, and the natural world. His pantheistic, or perhaps panentheistic, oneness with nature led him towards abstraction, as he sought to show how animals and humans were interconnected and immersed within the natural world. ‘In the Rain’ and ‘Doe in the Monastery Garden’ are among the images here that reveal his semi-abstract immersive style.

The modern spiritualism of Alexej von Jawlensky, which combined the best of different religious movements, led to a mystical focus on depictions of the human face and that of Christ, in particular. David Miller has suggested: “Jawlensky’s paintings are like no other’s. They are, at once, distinctly of their time – of the epoch shared with Kandinsky, Marc, [Emil] Nolde, [Karl] Schmidt-Rotluff – and extraordinarily ‘other’ in the way they affect a radical or authentic recovery of an old tradition, that of Byzantine and Russian ikonic art.” “Like the ikon painter,“ Miller states, “Jawlensky is concerned with an expressly spiritual emotion”, and the effect is “of a contemplative serenity.”

Kandinsky and Gabriele Münter both collected religious images to use as motifs in their work. These included votive paintings (commissioned to fulfil a spiritual vow) and carvings of saints and the Madonna. A selection of these is displayed in the exhibition, as are some of the images, such as Münter’s ‘Madonna with Pointsetta’, into which such items were incorporated. Münter and Kandinsky also experimented with reverse glass painting, primarily for religious art. Some of their work, like that of Natalia Goncharova, with whom they also exhibited, updated the religious themes and images of folk art in a more modern idiom, being a reworking of religious art for their times. Marianne Werefkin’s ‘The Prayer‘ provides a particularly strong example, as it is not only in this style but also depicts local people at prayer in their daily lives.

Other examples of such themes within the work of these expressionists are Maria Franck-Marc’s ‘Three Wise Men’, Albert Bloch’s ‘Entombment‘ and Lyonel Feininger’s paintings of churches, which are both symbolic and geometric.

The problem with allocating a specific room to spirituality in this instance, is that this distracts from the extent to which spirituality, in the same way, that the name of a seaside town runs through a stick of rock, runs through all that these expressionists individually and the Blue Rider as a group did. Alongside this is the fact that the catalogue strangely overlooks this aspect of these artists altogether, neither threading this theme through its essays to show how it informed the movement as a whole nor highlighting its significance by exploring it as a stand-alone topic.

This exhibition spotlights 17 figures – artists, musicians and performers – to show the unique nature of the transnational community of the artists known as the Blue Rider. The show draws on the world’s richest collection of expressionist masterpieces at the Lenbachhaus in Munich, alongside rare loans from public and private collections, to bring together a marvellous display of key works. Within this, a key focus is rightly on recovering the place and work of the group’s female members. These expressionist artists brought together broad and interconnected experiences, relationships and art practices, the diversity of which is amply demonstrated by this show. Threaded through it, though insufficiently articulated, are signs, images and artefacts of the spirituality that both motivated the Blue Rider and united it.

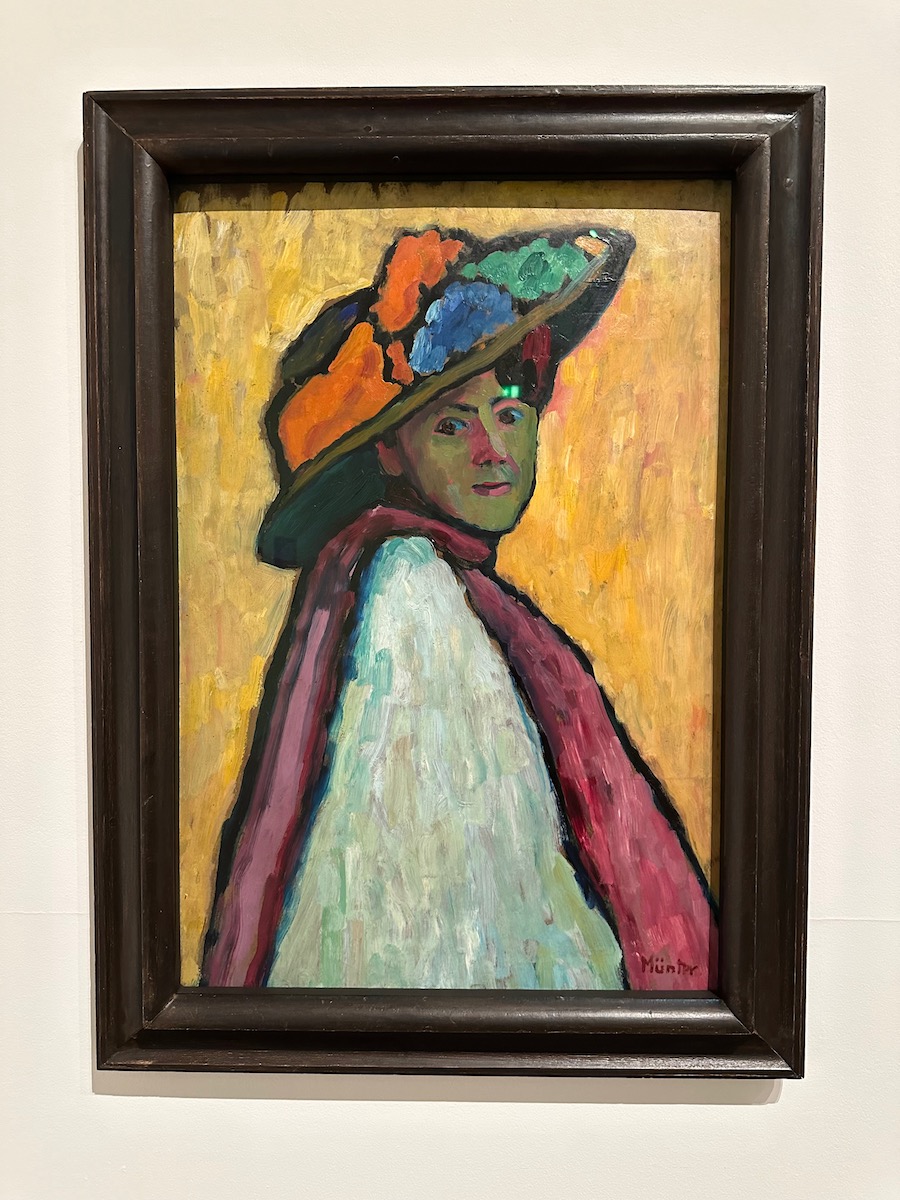

The exhibition has major works and stunning images at every turn, from Münter’s ‘Portrait of Marianne Werefkin‘ to Marc’s ‘Tiger’, from Jawlensky’s ‘Spanish Woman‘ to Werefkin’s ‘The Prayer‘ and from Robert Delaunay’s ‘Windows Open Simultaneously (First Part, Third Motif)‘ to Kandinsky’s ‘Riding Couple’. Yet, the foundational element to these marvellous works and the achievement of the Blue Rider is treated here as one theme among many rather than as the key to opening a treasure box filled with mystery, emotion, poetry and wonder.

Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider, 25 April – 20 October 2024, Tate Modern

Visit Here