In 1973, Marina Abramović performed Rhythm 10 at the Edinburgh Theatre Festival. Sitting at a table with twenty knives and two tape recorders, left hand splayed, right hand holding a knife, the artist played an old Slavic drinking game. The knife is jabbed between the fingers with increasing speed, in a rhythm that traditionally expresses the player’s bravado. “Every time you miss and cut yourself, you must take another drink. The drunker you get, the more likely you are to stab yourself. Like Russian roulette, it is a game of bravery, foolishness, despair, and darkness – the perfect Slavic game.”

Performing to an audience for the first time, Abramović turned the game into an act of endurance – surpassing the audience’s expectation of acceptable self-preservation and her own. Each time she cut herself, she would pick up a new knife from the row of twenty and record her next attempt. After cutting herself twenty times, she replayed the tape and listened to the rhythm of stabbing whilst trying to repeat the same movements. Somehow, she also managed to describe her pain to those watching. In this extraordinary, macabre display of endurance, the artist sought to “experience extreme mental clarity and presence”. Testing her body’s physical and mental limitations whilst under observation, her performance broke all theatrical codes of conduct – overturning the suspension of disbelief central to traditional theatre. “Once you enter the performance state, you can push your body to do things you absolutely could never normally do.” The audience witnessed real blood and pain. This transgression and the art world’s response set the artist on a lifelong enquiry into the state of consciousness of the performer and, by extension, our assigned roles in society.

Abramović pioneered a new notion of identity contingent on observers’ participation, focusing on “confronting pain, blood, and physical limits of the body”. In other words, she was violent towards herself, with the audience both condoning and later engaging in the violence. She was “prepared to die” for her art. Fifty years later, The Royal Academy is staging a major retrospective. Unbelievably, it is the first time a female artist has had a solo show in the Main Galleries of the Royal Academy. The first question that springs to mind is whether extreme violence or unique bravery are necessary for women to be taken seriously in a man’s world. Whilst gender was not the primary focus of her work, perhaps by defying the stereotype, she was given a seat at the table.

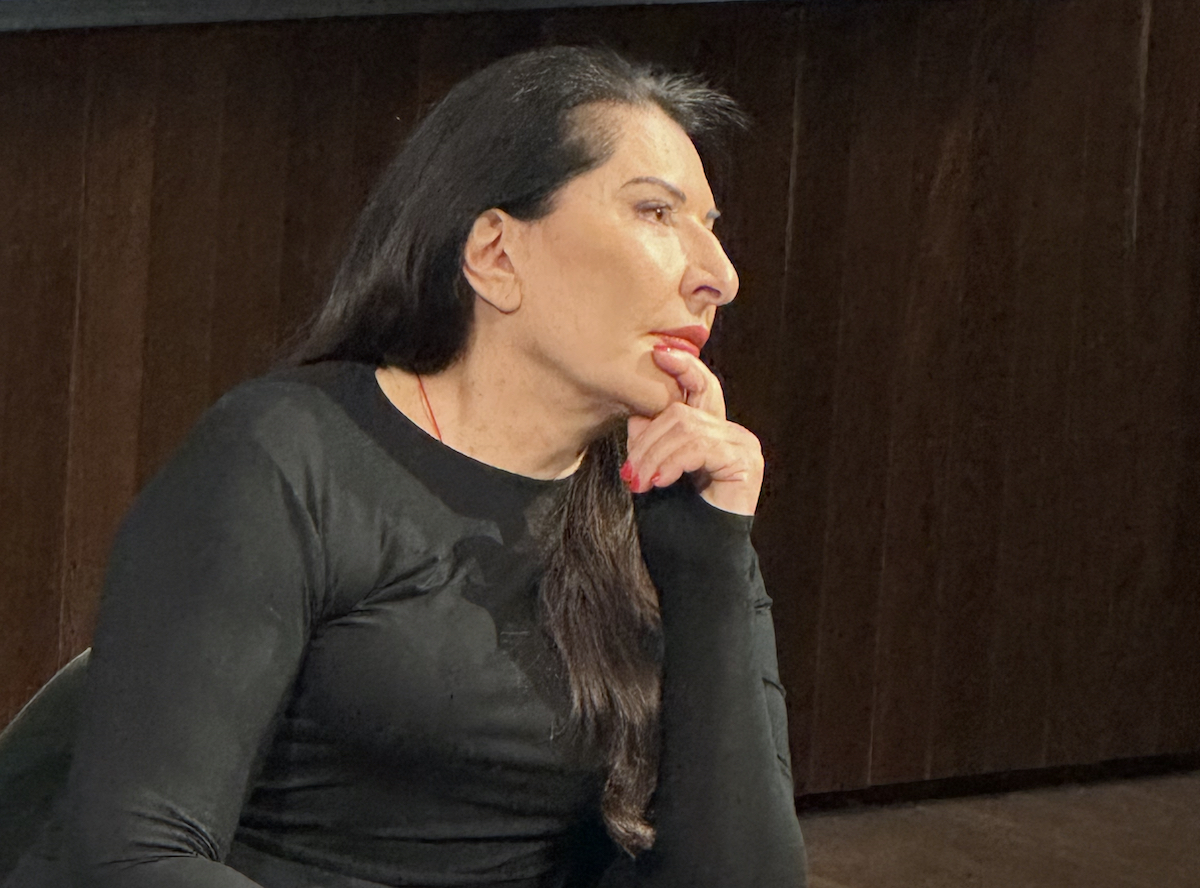

Born in Belgrade, former Yugoslavia, on November 30, 1946, Abramović is now 78 years old and refers to herself as “the grandmother of performance art”. Remarkably, she has continued to conceive of performances over five decades despite its physical demands on the body. As our editor Paul Carter Robinson observed at the opening, “She has transcended her era in her lifetime”. When Abramović began, her works had the character of a counter-cultural exercises with a practice rooted in an economy of means beyond the space of formal representation. The 1970s was a time of profound socio/politico change, and somehow, her performances carried the promise of transformation for both her artistic self and those who witnessed the act. Instead of attacking the status quo, she publicly attacked her body and put herself in increasingly vulnerable, dangerous or terrifying situations to highlight what was fundamentally wrong with our society – not in the least that violence against women has been silently sanctioned for so long. Her suffrage was self-sacrifice.

The context of her first performance is key – one of the world’s leading theatre festivals, amidst actors standing on generations of training both mind and body. For an actor, the transformation process of assuming a new role usually occurs during rehearsals before any public performance. Rhythm 10 was intensely interactive and as shocking as Antonin Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty, which broke from traditional Western theatre by its determined assault on the audience’s senses. From this, Abramovic launched or instead defined, her genre of performance art in which the limits of the body and the possibilities of the mind as both medium and subject were to be explored. Her performances were arduous and gruelling. Importantly, she began making art behind the iron curtain of communism. When she left in 1976 to join her partner and collaborator Ulay (Frank Uwe Laysiepen, 1943 – 2020), whom she met on her birthday in 1975, performing ‘Lips of Thomas’, she continued to question the invisible barriers that delimited our minds, and the spaces – galleries and museums – that perpetuated this.

The main criticism of her early works was that they were circus acts, sensational expressions of a narcissist. Abramović responded with terrifying brilliance in the work Rhythm O, 1974, fundamentally testing the relationship between performer and audience.

Her instructions were

Instructions:

There are 72 objects on the table that one can use on me as desired.

Performance.

I am the object.

During this period, I took full responsibility.

Duration: 6 hours (8 pm – 2 am).

Invited to use the 72 objects however they chose, a sign informed the audience that they held no responsibility for their actions. Some things could give pleasure, while others could be wielded to inflict pain or harm her. Over six hours, the artist stood passively whilst the audience acted upon her as they wished. It began gently, respectfully, and then things began to unravel; clothes were ripped, skin slit with a rose thorn, then a blade, and finally, a loaded gun was placed in her hand. As Abramović described it later: “What I learned was that … if you leave it up to the audience, they can kill you. … I felt violated: they cut up my clothes, stuck rose thorns in my stomach, one person aimed the gun at my head, and another took it away. It created an aggressive atmosphere. After exactly 6 hours, as planned, I stood up and started walking toward the audience. Everyone ran away to escape an actual confrontation.”

If we are present during the performance, there is an exchange – we watch, feel, and then question our own response. Perhaps Abramović asks us to consider all the little, accumulative, thoughtless, mindless actions in our daily routines. Her idea is to give “cathartic expression to universal experiences of pain, anger and fear”. Intensely emotive and triggering, her performances break all norms of human interaction and highlight the dangers of inaction and passive acceptance.

In the exhibition’s second room, we approach a large screen with the performance replaying in grainy, black-and-white unreality. Beneath it is the table, reconstructed to include all 72 objects: every kind of knife, hatchet and scissor, a rose, a feather, honey, a whip, a scalpel, a hat and a gun with a single bullet. A guard stands next to the table inside a white line. I approach the weapons, wanting to see if they are tied down. The guard smiles and says in anticipation, “You can look, but you can’t touch, and they are secured down”. I am still taking in the glint of a knife edge when a voice beside me says, “It’s incredible”. I turn to see a young man and respond, “A fan?” He smiles broadly, “I flew in, especially for the opening!” I am taken aback, unnerved at our proximity to weapons and his near-fanatical tone. Sensing this, he says, “I did her method (Cleaning the House) and it changed my life. Four days of no food, no speech, and just walking. It was incredible.” Repeating the word.

“Why?” I ask.

“Because I was afraid of everything.”

“Did it work?”

“Yes, I am fearless.”

“Are you an artist?”

He hesitates, then smiles and admits, “Yes, but I am not quite sure of my medium.”

Walking away from this stranger, I entered the red room, full of all its heavy communist symbolism. Here, we are reminded of Abramović’s past and that breaking down the strange, invisible barrier between audience and self might have something to do with the fact that she was born under a communist regime in a country that no longer exists. The strictures of this ideology – extreme physical discipline and restricted freedom of speech shaped her early years, compounded by a brutally authoritarian mother who tried to beat any desire to “show off”. Her release came in the form of burning the communist five-pointed star, Rhythm 5, followed by incising the star on her abdomen in ‘Lips of Thomas’.

In the introduction to the monologue accompanying the show, Andrea Tarsia says, “These works resonated with post-war European thought more broadly, from existentialism to phenomenology and post-structuralism, carrying out a symbolic voiding of the body to reconstruct it anew through a meaningful, essential experience of the world. In the wake of the horrors of the Second World War, this was a performance demanded by Artaud, Grotowsky and others: a return to Ancient Greek collective, cathartic ritual traditions.”

I wish this show had included eyewitness accounts of those seminal performances. What was felt by her audience at that time? While we cannot go back to that moment, Abramović has addressed the question of repetition by founding the MAI, preparing the next generation mentally and physically to perform some of her most iconic works. The Royal Academy show has performers – mostly naked – performing. Looking at two artists standing motionless opposite each other at the entrance to the next room, I wonder whether her institute was also born out of the loss she suffered when the most important relationship in her life ended.

At the end of her performance, ‘Lips of Thomas’, Abramović met Ulay and both experienced an instant emotional and artistic connection. As partners equally interested in pushing the body’s limits to create art, they made work that explored the relationship between the self and the other. Over time, their lives became so intertwined that they expressed this duality as “That Self”. During their first year, they lived like nomads and wrote An Artist’s Life Manifesto, but the ultimate expression of their relationship was the unrepeatable work ‘Rest Energy’ (1980). Shown in a loop at the back of Room 4. (Body Limits), the audience must navigate four split screens on the way there, with Abramović and Ulay in perpetual motion, screaming at one another. We are drawn into the work by the tension and near stillness of Ulay holding the end of an arrow, which is drawn in a bow, held by Abramović, and pointed straight at her heart. As we begin to understand, we hear the sound of a galloping heart – or is it two? Instinctively, I raise my hands to my chest, clutching my heart. I watch, I feel the heartbeat, and soon, I can no longer tell if they are around me or coming from inside me. It is phenomenally clever and wrenching.

Next door (5. Absence of the Body), we learn that this relationship would end on a long walk towards and away from each other on the Great Wall of China. They would not meet again until Abramović re-performed a work at the MoMA’s landmark exhibition, The Artist is Present, in 2010. When Ulay sat down at the table across from Abramović, she broke protocol and reached across the table for his hands. Ulay would later say that he was very against the idea of repetition and re-performance, “but now that these works have been accepted into institutions, I can see there is a powerful logic in this.” Certainly, and their power is manifest at the Royal Academy.

Words Nico Kos Earle / Photos P C Robinson © Artlyst 2023

Marina Abramović has been announced to feature in Art of London’s late-night arts programme Art After Dark returning on 12th – 13th October 2023, featuring a giant public art takeover alongside 30+ iconic galleries staying open late in London’s West End.

Excitingly on Friday 13th October, an exclusive screening inspired by iconic performance artist Marina Abramović will be exhibited on the Piccadilly Lights and celebrate the Royal Academy of Arts’ major autumn show. The Royal Academy of Arts, the National Gallery and National Portrait Gallery, will then stay open late until 9pm for evening culture seekers.