Since its heyday in the 1990s, when it helped to establish the reputation of the last really significant art movement in Britain – or perhaps anywhere else – that of the so-called YBAs or Younger British Artists – the Turner Prize has been in decline. Perhaps its last significant outing was in 2007, nearly ten years ago, when it was won by Mark Wallinger. Since then, try to recall the names of the lucky laureates. Oh yes, in 2015 it was won by a community activist group called Assemble, full of good intentions but they don’t, as far as I can recall, actually describe themselves as artists.

Helen Marten

There have been several reasons for this decline. First, the fragmentation of the concept of ‘avant-gardism’. In what one may now paradoxically call the traditional sense, the concept of an avant-garde no longer exists. The YBAs were perhaps its final manifestation: the conclusion of a trajectory that began in the early 19th century with the German Nazarenes, followed by the British Pre-Raphaelites. We Brits have always been good at coming last in that kind of thing. We don’t have much talent for embracing the future. In technology, maybe we are willing to do that – but not where art is concerned. The idea of a British Futurist is an oxymoron. The Pre-Raphs became avant-garde by dint of embracing the past

Second, there has been the huge success of Tate Modern, which has tended to relegate what happens at Tate Britain to a secondary role.

And third, there has been the do-gooding decision to banish the Turner Prize exhibition to various provincial centres – in 2007 to Tate Liverpool; in 2011 to the Baltic Centre in Gateshead; in 2013 to Derry, and last year to Tramway, in Glasgow. Next year it goes to Hull. One can understand the democratizing, inclusive impulse that inspired this, but it has tended to diminish the amount of publicity the Turner gets in these off years, and there have been occasional comic consequences – for example, the story about school kids in Derry being shepherded away from aspects of the show there, as these were locally considered to be unsuitable fodder for the young.

Anthea Hamilton

The current Turner Prize show does offer some signs that the tide is beginning to turn. There is no longer a heavy reliance on video. There is no performance art. You go there. You look – at your own pace. What you get out of it is strictly a matter of your own personal relationship with what is presented to you. Inevitably there is some moralizing – for example, all those pennies spread on the floor, in the section occupied by Michael Dean, to represent a yearly poverty-level minimum wage for a family of four.

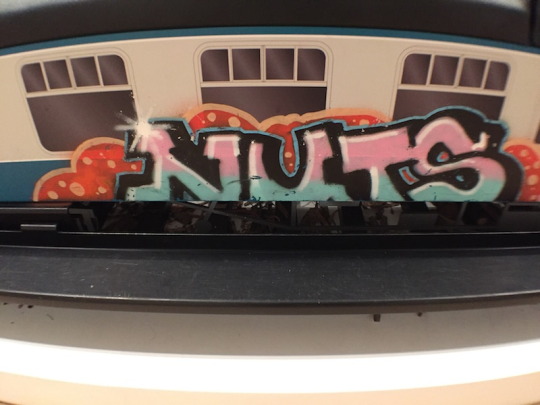

Josephine Pryde

The four sections, one for each Turner Prize finalist – Michael Dean, Anthea Hamilton, Helen Marten, Josephine Pryde – are in fact four different theatres. In each case, the individual spectator is an actor, entering into a relationship with the artist who has provided in the setting within which he or she now acts or reacts. In the good sense of the phrase “It makes you think, don’t it?” And it’s the kind of art that for the most part only works in public spaces. There is nothing much here that posh people can buy and squirrel away in customs-free zones in Switzerland and Luxembourg. A few bits of sculpture, perhaps, that would look pretty much orphaned without the context provided for them here.

Of course, there are aspects of the show that tell you pretty firmly “Don’t kid yourself – this is the year 2016.” There are three women artists to one man. One of the women, to judge from her catalogue photograph, is mixed race. So far, so politically correct.

Forced to choose, I would hand the prize either to the guy or to Anthea Hamilton, the artist who seems to be mixed race. Dean’s idea of transforming written phrases into sculptural objects is an interesting one. The sheer awkwardness of the resulting forms grabs one’s attention. Slick and elegant they aren’t.

Michael Dean

The dominating object in the show, however, is the enormous human backside jammed in a doorway, two hands lewdly spreading its cheeks apart, offered by Andrea Hamilton. On a much, much bigger scale, this is a bit like the plaster casts of female torsos, cigarettes stuck up their twats or fannies, offered to the public gaze by Sarah Lucas in her show in the British pavilion in the 2015 Venice Biennale. Rude girls live, OK!

It is, however, saddening to learn that this challenging item is not an invention but an appropriation. As the catalogue honestly informs one:

“Originally conceived by the architect and designer Gaetano Pesce in the 1970s as a proposal for a doorway into an Upper East side apartment building, the idea lay dormant as a small model in the designer’s archive until Hamilton realized it – as a sculpture, not a functional architectural feature – decades later at the SculptureCenter.”

I guess Brit art is still going back to the future.

Turner Prize 2016 at Tate Britain 27 September 2016 – 8 January 2017