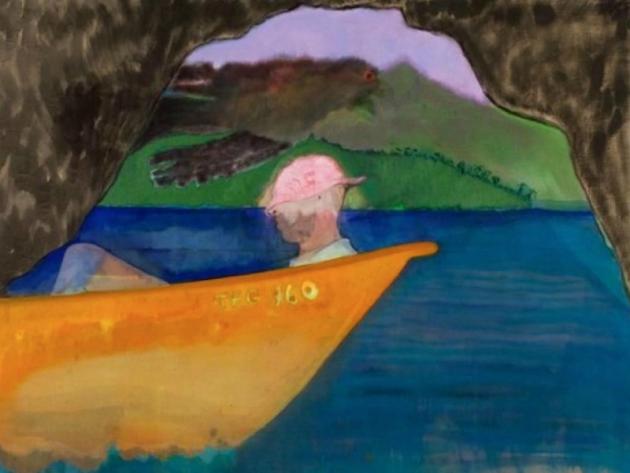

In Peter Doig’s show the other day, speaking with the charming girl working there, I was told that Peter Doig had finished the pink hat on ‘Cave Boat Bird Painting’ (2010-2012) in the gallery, as it was hanging there, hours before the opening. This anecdote has some importance to the entirety of this exhibition. The important question I will address is as follows: “Why did Peter Doig finish the pink hat?”

Another fact about Peter Doig: his paintings used to sell for around £8,000, then Charles Saatchi sold one for £5.7m in 2007. The painting was called ‘White Canoe’. The painting belonged to Saatchi, and Doig apparently didn’t see a penny. Then there was a Tate retrospective in 2008, a Michael Werner show in New York, 2009, and then this inauguration of Michael Werner’s London space, 2012. Doig was a firm fixture in the British art scene before 2007 – this is important to remember – with shows at Victoria Miro and a 1994 nomination for the Turner prize. Exhibition-wise, Doig has actually slowed down since he became worth millions of pounds.

Bearing all that in mind, I would now like to take a long route outwards, then back to Peter Doig and specifically the paintings he has on show at the Michael Werner Gallery from 27th September to 22nd December 2012.

In 1983 a man called Donald Hall, who was a poet, decided to speak about poetry. Poets are always speaking about poetry, but the difference between Donald Hall and other poets is that I am about to quote Donald Hall at length, from that 1983 essay ‘Poetry and Ambition’. I’m doing this because I believe there to be parallels between the views espoused within and the situation now in the art marketplace, and I believe these views are a good way to look at Peter Doig’s recent show. Donald Hall:

‘I see no reason to spend your life writing poems unless your goal is to write great poems.

An ambitious project—but sensible, I think. And it seems to me that contemporary American poetry is afflicted by modesty of ambition—a modesty, alas, genuine … if sometimes accompanied by vast pretense. Of course the great majority of contemporary poems, in any era, will always be bad or mediocre. (Our time may well be characterized by more mediocrity and less badness.) But if failure is constant the types of failure vary, and the qualities and habits of our society specify the manners and the methods of our failure. I think that we fail in part because we lack serious ambition….

True ambition in a poet seeks fame in the old sense, to make words that live forever. If even to entertain such ambition reveals monstrous egotism, let me argue that the common alternative is petty egotism that spends itself in small competitiveness, that measures its success by quantity of publication, by blurbs on jackets, by small achievement: to be the best poet in the workshop, to be published by Knopf, to win the Pulitzer or the Nobel. . . . The grander goal is to be as good as Dante.’

‘Overproduction as a response to eminence’ is another thing Donald Hall picks out. How do you combat that?:

‘Horace, when he wrote the Ars Poetica, recommended that poets keep their poems home for ten years; don’t let them go, don’t publish them until you have kept them around for ten years: by that time, they ought to stop moving on you; by that time, you ought to have them right. Sensible advice, I think— but difficult to follow. When Pope wrote “An Essay on Criticism” seventeen hundred years after Horace, he cut the waiting time in half, suggesting that poets keep their poems for five years before publication. Henry Adams said something about acceleration, mounting his complaint in 1912; some would say that acceleration has accelerated in the seventy years since. By this time, I would be grateful—and published poetry would be better—if people kept their poems home for eighteen months.

Poems have become as instant as coffee or onion soup mix. One of our eminent critics compared [Robert] Lowell’s last book to the work of Horace, although some of its poems were dated the year of publication. Anyone editing a magazine receives poems dated the day of the postmark. When a poet types and submits a poem just composed (or even shows it to spouse or friend) the poet cuts off from the poem the possibility of growth and change; I suspect that the poet wishes to forestall the possibilities of growth and change, though of course without acknowledging the wish.’

Peter Doig finished the pink hat hours before the opening, in a world that measures its success on auction prices, exhibition frequency, and public exposure. The accusation this suggests isn’t a particularly grand one, and is of the type that is levelled at practically every big-bucks artist: cynical profiteering, complacency, and perhaps a ‘petty egotism’ of the kind Donald Hall describes. I don’t think this is why Peter Doig finished the pink hat hours before the opening.

If you need to make paintings for a new show the easiest thing to do is make a series – a tactic recently skewed by Adrian Hamilton in The Independent’s recent review of Luc Tuyman’s show at David Zwirner (another inauguration of an American gallery’s London space). Come up with an idea that bears repeating, knock the paintings out, finish them, pass them on to a gallery.

Doig’s work in this exhibition doesn’t seem to follow that model. For a start, many of these works seem to have been in the pipeline for a long time: “Cricket Painting (Paragrand)” (2006-2012); “Painting for Wall Painters (Prosperity P.o.S.)” (2010-2012); “Figure by a Pool” (2008-2012); “Fall in New York (Central Park)” (2002-2012); “Cave Boat Painting” (2011-2012); “Cave Boat Bird Painting”, (2010-2012) (this is the one with the pink hat, sat atop a sleeping Doig). “A painting is a living thing,” says Doig in a recent interview with the Financial Times, when asked how he knows a painting is finished. “It’s finished when it’s let go, when it’s out the door. I’ve realised what I like in other artists’ paintings is when they’ve been left open and not shut down. I’m learning to do that.” Donald Hall sees this as forestalling the possibilities of growth and change.

But in the same Financial Times interview, Caroline Roux notes of his “Cricket Painting” that ‘a pair of cricketers have, judging by residual lines, already made several moves within their own brilliant orange-and-black world.’ “I could make a painting a week,” said Doig, “but I don’t. I spend 10 hours a day in my studio. Always. But sometimes I don’t start anything until 5.30[pm].”

Doig clearly isn’t one who overproduces in response to eminence. Some of these paintings he has kept for nearly as long as Alexander Pope says you should withhold a poem for – 5 years. “Fall in New York” has been left to be considered for the full 10 years Horace recommends. He has a patience and a dedication to re-working that aligns him with painters that have grand ambition. Some of the photographs that make the paintings here have been used before. The cricket painting is the same photograph as “Paragon” (2005), shown in the 2008 Tate retrospective. The rollerskater from “Fall in New York” almost made it into “The Heart of Old San Juan” (it is present in a 1999 “study for The Heart of Old San Juan”). He keeps things back, waiting for a use of them. “A photograph is a way of remembering shapes”, Doig has said. Certain shapes find their way back.

But if he has been saving that photograph since 1999, it seems odd to me to finally put it out in “Fall in New York”, after a decade of it sitting facing a studio wall. “Fall in New York” shows the female figure, on rollerskates, mid-roller-disco move, against a faded black background with dark green shapes to represent leaves. It seems an underwhelming end to such a long-running intent and experimentation.

In 2002 Doig moved to Trinidad, which could draw accusations of him “doing a Gauguin”, with all that implies post-Colonial-wise, but he hasn’t. What seems to have happened in around 2002, however, is a shift in the average style of work he makes. Doig has had many masters – Impressionist winter landscapes in the early 1990s, but also a Munch-style early witticism in “Art School” (1990) featuring three chipmunks poking out a tree. But always containing a kind of hidden narrative force and a drawn line (that occasionally approaches an illustrator’s finepoint) that recalls Brueghel the Elder (albeit with less figures and a more fairytale touch), as in “Gasthof zur Muldentalsperre” (2000-2002) (compare Bruegel’s 1565 “The Harvesters”).

Since 2002, he seems to have shifted his average style (Doig is eclectic and hard to pin down precisely) to much thinner paint that often shows the unprimed canvas through it and a more fluid expressive line, like Matisse’s drypoint etchings, that is reminiscent of his friend Chris Ofili who moved to Trinidad in 2005. In this shift he seems to have swapped an engaging narrative drive – painting where a place was drawn for an imagination to inhabit – to a kind of line and painting designed to be expressive in itself. Doig’s work has become more about being images, and less about what the images are. “Painting for Wall Painters (Prosperity P.o.S.)” is a very flat painting of a wall of flags, from a real-life wall of flags in a Tahitian bar. The flags look to have been sun-bleached of their vibrant colours because of the thinness of Doig’s paint.

This work is O.K., I suppose, but lacks the spark of Doig’s earlier work. It feels like Doig is working through something here, in this exhibition, and the length of time spent on some of these pieces suggests to me that he still would be working through some of them were it not for the abrupt end-date of an exhibition. These works feel like they are only finished because they are up for sale. There is some evidence that Doig is getting there again. “Lion in Sand” (2012), where a kind of smoky figure that resembles the Lion of Judah prances through the middle section of a light-blue/green, white and red flag – that due to the texture occasionally becomes a desert – is one of the smaller paintings in the exhibition but also a highlight. Overall though, this exhibition seems like serious ambition bought out into the petty necessities and ambitions of the world of commercial art. I don’t think this is Doig’s fault. Why did Doig finish the pink hat just hours before the exhibition opened? To try to finish, in the nick of time, what he hadn’t been able to do in a year?

**** 4 Stars Words by Jack Castle © Artlyst 2012 Photo: Peter Doig, “Cave Boat Bird Painting”, Oil on linen, 2010-2012.

Peter Doig, ‘New Paintings’, Michael Werner, 27th Sept- 22nd Dec 2012