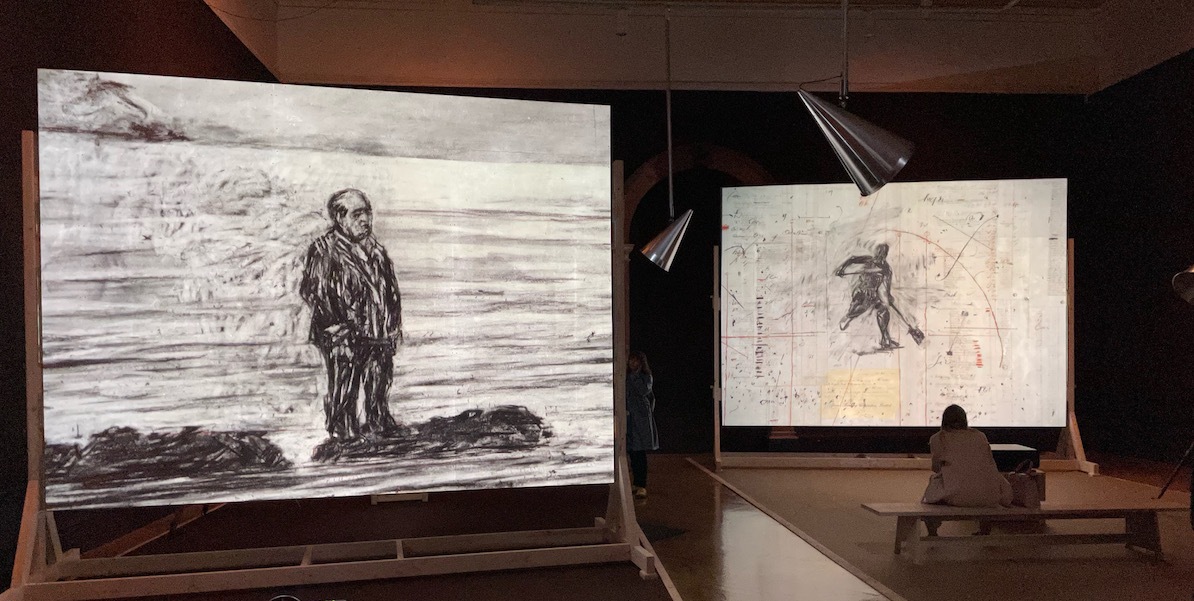

“Drawing is the starting point to nearly all of Kentridge’s work. He sees drawing as a testing of ideas, a slow-motion version of thought.” Charcoal is the medium he works with most; it’s easy to rub out and you can change your composition ‘as quickly as you can change your mind’.” Portraits “fall apart; sumptuous bunches of flowers disintegrate; text and buildings are projected and then disappear.”

Kentridge’s art is shaped by apartheid and grounded in the politics of the post-apartheid era

“Kentridge is an artist of black and white … who uses drawing, animation, film, theatre, sculpture, opera, and even tapestry, to make compelling works that interrogate some of the darkest corners of history and the human psyche.” His “40-year career combines drawing, writing, theatre, puppetry, opera, film, dance, sculpture, tapestry and performance. The works are huge in scope but also huge in scale: there are floor-to-ceiling drawings, four-metre tapestries, multi-screen films, mechanised theatre sets, and stage performances with huge casts.” He asks, “do I have the courage of my convictions in saying, “Let’s cut things up and fragment them and try to reconstruct them?” “What are the surprising connections that emerge, as one is in the process of editing, doing [a] kind of montage?”

“His source material is vast – he draws inspiration from African porters in the First World War and the Russian Revolution. He melds geographies, visual and technical histories with layers of artistic and political references. His navigational axis runs between Europe, Africa and China, between the past, present and future unfolding from that history. Music flows through everything, ranging from Mozart and Hindemith to African brass bands.” “This man is colonising the world. He started off with Johannesburg landscapes and he’s gone outwards, through Stalinist Russia and to Mao’s China and Vienna in the nineteen-twenties and on and on until there’s not going to be any territory in the world left that he hasn’t colonised with his drawings.”

“As elusive as it is allusive, Kentridge’s art is shaped by apartheid and grounded in the politics of the post-apartheid era, and in science, literature and history, while always maintaining space for contradiction and uncertainty.” He says, “There was an absurdity to the basic logic of apartheid that we grew up with. There was something wrong with the logic, and that false logic then gets carried through to the nth degree—with pencils in people’s hair, with the fifty-two different categorisations of what races were. So, the absurd was built in. We understood that the absurd was where we lived.”

“The ‘real work,” he says, “is the drawing or the work in the studio, in the sense that all the conversations—all the conversations in the book, the lectures, the performances—always come after the work, and they’re often a reconstruction of a possible origin of different projects, or the way work might have begun.” His Drawing Lessons films, for example, “present him engaged in animated, often humorous, conversations with himself about his work.”

“The technique used for what the artist has called ‘stone-age filmmaking’ of [his animated] works is based on creating a series of drawings in charcoal and pastel on paper; each is successively altered through erasure and re-drawing and photographed at the many stages of its evolution.” “Through his artistic technique of incomplete erasure, he reveals the continuing effect of the past on the present: Kentridge draws an image or scene, which he photographs and then ‘erases’. These ‘erasures’ leave behind imprints, or smudges, which he then draws over, which morph into different images, and different meanings.” “The viewer, drawn to the haunting shadows that these erasures cause as the drama unfolds, often at speed, is left to wonder what is real and what is not.”

“Kentridge’s films are made up of hundreds of moments in the ongoing progress of a small number of drawings, from about twenty for shorter films to about sixty for longer ones, so that each leftover drawing corresponds to the final stage of a scene in the film.” His triptychs, including The Conservationists’ Ball, “portray a single scene from multiple viewpoints, positioning the viewer as a witness to an unfolding drama rather like being in the audience of a theatre where no-one shares the same view of the play enacted on stage.” “Narrative emerges through a sequence of broadly related scenes and recurring ‘personae’ reflecting different perspectives on the world and various parts of the artist’s self.”

“The characters who people his projects – the greedy capitalist Soho Eckstein, his lovesick alter ego, Felix Teitelbaum, Ubu the absurd potentate, the old-fashioned typewriter, the giant megaphone, the nose from Gogol … invented for one-off use in specific works … ‘now function like Commedia dell’arte – they can be pulled out of the cupboard and perform whatever role, they can inhabit whatever film I want to make.’ Kentridge adds, ‘They are a vector through which the world can be looked at.’” So, “the world meets the act of drawing halfway.” “Crude, unstable, insistent, monochrome images point beyond the stylish scenery and colour-coordinated costumes to the fragilities and obsessions that drive the plot to its tragic conclusion. ‘One has to think of the black ink as blood,’ Kentridge explains to his team, ‘and the brush mark as a dagger stroke.’”

“The process of facture remains visible, establishing a jerky effect (tempered by music) that causes the viewer to perceive the spatial and temporal disjunctures of the drawing, rather than creating an illusion of fluid movement.” So, “his work physically depicts layers of reality, a reference to his drawings and erasures — the supposedly dominant and ‘official’ present and the unsuccessfully erased past. In other words, he depicts memory itself.”

“This technique engenders a time-based, open form of ‘process’ drawing, a form of drawing that can never be ‘definitive’. This openness to change and un-finiteness of language is an aesthetic position based on a political perspective- a refusal of all authoritarian and authoritative forms of communication embedded in most usages, from advertising to politics.” His is an “Art of the State of Siege, ‘where all the ambiguities and uncertainties are present, but it is not a retreat from the world nor a triumphalist confidence in how the world will unfold.’ Certainty, as he sometimes remarks, leads only to the Killing Fields of Pol Pot.”

This focus on uncertainty culminates in Sibyl, “a reinterpretation of the Greek myth of the Cumaean Sibyl”, who “would write your fate on an oak leaf and place the leaf at the mouth of her cave, accumulating a pile of oak leaves. But as you went to retrieve your particular oak leaf, a breeze would blow up and swirl the leaves about so that you never knew if you were getting your fate or someone else’s fate. The fact that your fate would be known, but you couldn’t know it, is the deep theme of our relationship of dread, expectation, and foreboding towards the future.” “The idea of turning the leaves into pages, and the pages swirling around … became the starting form for the piece, to think of those leaves swirling around and what future could or couldn’t be known.”

“Plato’s allegory of the prisoners in the cave is, perhaps unsurprisingly, the text that continues to inspire all of Kentridge’s work. As he said in the first of his 2011–12 Charles Eliot Norton Lectures, Six Drawing Lessons, ‘The questions it provokes, its metaphors, are the pivotal axes of questions both political and aesthetic.’ After all, it is largely in the dark that his works unfold – in theatres and blacked-out galleries – with films and animations flickering urgently on the wall.”

He also writes of “Plato’s term metaxu [which] describes that which separates and connects, an ironic or oxymoronic, contradictory position. It makes me think of the wall between two prisoners that separates them, but that also makes communication possible through knocking. Or a window that separates you from the view outside but also frames the view and makes you aware of what you are looking at. Metaxu also refers to an “in-between state”, between being separated and connected, between quotidian, everyday reality and the world of mystery and transcendence beyond … We understand that the safe place is within that journey. The terror is the terror of arriving. Because once it is arrived at, the mystery disappears and, in its place, comes authority, the final word, the last book, the law which must be obeyed, and all the punishments that follow … the very activity of making the work involves the artist in a journey of going from what is known to what is glimpsed at, half understood and tentatively approached with the work.”

Words: Revd Jonathan Evens Photos: Sara Faith

William Kentridge, Royal Academy of Arts, 24 September – 11 December 2022

In homage to Kentridge and his approaches, this review is a montage of quotes about his work drawn from the following: Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev; Emma Crichton-Miller; Denis Hirson; Beschara Sharlene Karam; William Kentridge; and Royal Academy