At the first UK exhibition dedicated solely to William Nicholson since 2004, one witnesses his range, incredible artistic scale, and skill. Nicholson was adaptability personified and worked between and in so many media. His painting was close to contemporary European advances in art. He seems to have shut the door on formal art movements. He was a bridge between Victorian England, the Empire and the Great War era. His painterly style may have been closer to Manet’s and far from the contemporaneous movements like Impressionism, Expressionism, Cubism and the like. A William Nicholson portrait is more personable, less overtly presentational than the earlier John Singer Sargent, whose Madame X (1884) had seized centre stage for portraiture in the 19th century…

William Orpen’s A Bloomsbury Family (1907), a group portrait of the entire Nicholson family around a table, portrays William Nicholson somewhat aside from the group in a special place. You get the sense of what Max Beerbohm once called the Nicholson family, “more like a troupe than a family”, from Orpen’s portrait. Among the best painted portraits in the show are Nicholson’s earliest. They include those of J. M. Barrie and Sir Max Beerbohm. These are social portraits, even if the backgrounds are neutral, for they capture the Victorian essence of these public personalities with skill. Equally fine is an animated portrait of actor Wish Wynne.

William Nicholson is something of an anomaly in British art of his era. Never a member of any art movement, always pertinent, Nicholson had a reputation as something of a metropolitan dandy, in the French mode. It was all about “l’allure”, the look and fashion sensibility. Seen with a flourish of tassels and feathers, an elegant hat, William’s daughter in Nancy and Feather Hat (1910) has a theatrical presence. Subdued, accomplished, the portrait Ben Nicholson as a Child of Six or Seven Years (1901) of son Ben is stoic and subdued, but as conventional portraits go, atmospheric and accomplished. This was the era when modern art movements were taking the art world by storm, even if the public was not always tuned in to it.

William Nicholson (1872 – 1949), Gold Jug, 1937, oil on canvas board, 409 x 327, Lent by His Majesty the King

© Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025 | All Rights Reserved

There are superb examples of Nicholson’s still lifes in the show… Rose Lustre (1920), The Gold Jug (1937), The Silver Casket and Red Leather Box (1920). As son Ben evolved into an abstract painter, William would comment, “I don’t know what has happened to Ben, he used to paint so nicely.” Interestingly, Ben Nicholson attributed his interest in the still-life theme to his father and not to Cubism. As Pallant House Director Simon Martin comments, “his approach to rendering light and tone was essentially abstract”, and herein is the aesthetic link between the two generations of Nicholson painters.

As the late Sir Alan Bowness has said, Nicholson “made and abandoned several reputations.” Graphic design and book illustration seem the most salient. They remained to this time. His commercial works, like an early stencil on paper, Shakespeare’s Hamlet (1894), the first work Pryde and Nicholson ever made for J & W Beggarstaff sans pareil, to my mind. Others on view include Rowntree’s Electric Cocoa and Cinderella (1895) on Drury Lane, prove Nicholson’s mastery of design in an age of transition.

With a wide range of artistic skills, Nicholson also designed costumes for Peter Pan (1904) and Noel Coward’s Marquise (1927). The most important of all is William Nicholson’s contribution to book illustration: The Velveteen Rabbit (1922), a collaboration with Margery Williams published by William Heinemann. Various vitrine cabinets display Nicholson’s published materials and sketches, including The Owl, The Book of Blokes, W. H. Davies’ The Hour of Magic, The Square Book of Animals, and Polly by John Gay. We see original drawings for Clever Bill (1926), a book he wrote and illustrated that gives a sense of Nicholson’s lively, slightly askew sense of humour.

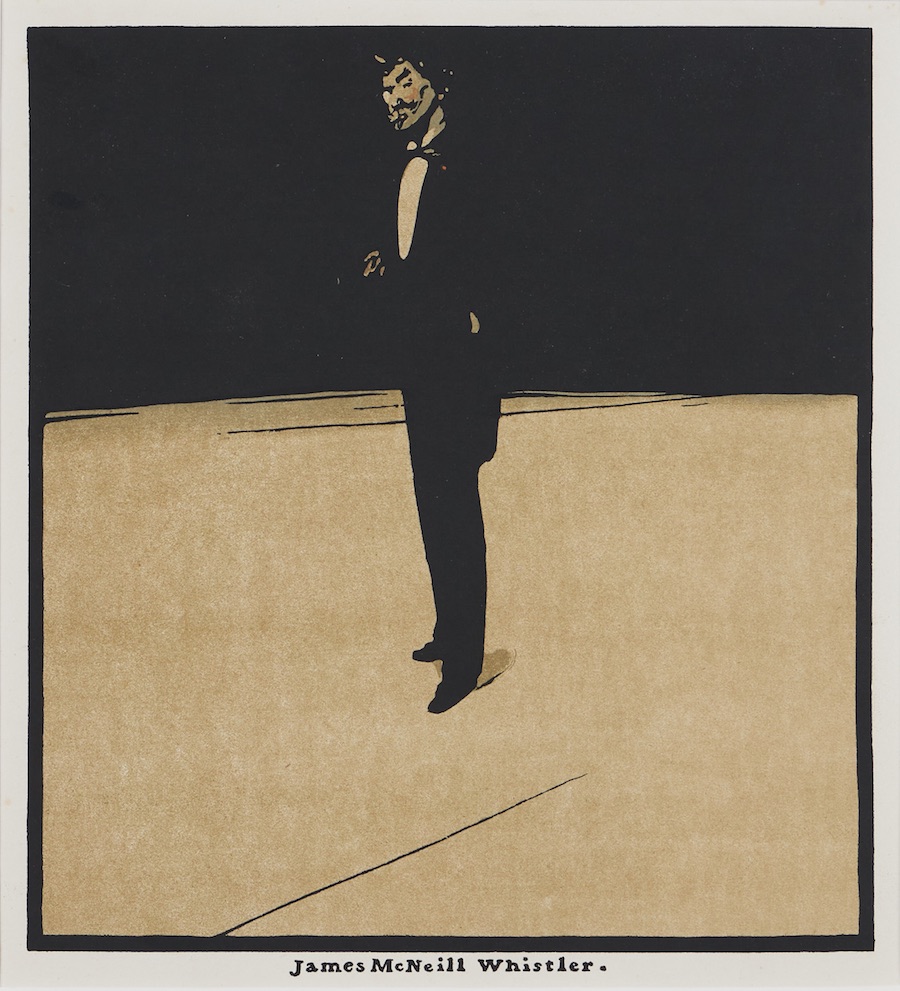

William Nicholson (1872 – 1949), James McNeill Whistler, 1897, Lithograph from the original woodblock, 245 x 225, Muriel Wilson Bequest (2019)

Nicholson’s characters of London are quintessentially British. Lovely renderings of a cab driver, a bar lady at the pub, a man wearing a sandwich board ad, all the things that made London great. This reveals the ordinary people Nicholson loved to portray, as much as the renowned “artsies, writers and royalty”. The common man had a place in Nicholson’s pantheon. It was through publication that Nicholson’s name established itself, notably the popular A to Z portraits from An Alphabet (1898). They continue to be collected and are admired to this day for their brazen, bold styling and post-Victorian aplomb. The portrait illustrations of public and renowned alike made Nicholson’s name, as much as portrait commissions. Rudyard Kipling’s An Almanac of Sports, illustrated with Nicholson’s images of sporting life as well as the prints he made of James McNeill Whistler, Sarah Bernhardt, and Queen Victoria, are as good as graphic gets.

Somewhat less spectacular, but tasteful in their super natural evocations of the Sussex landscape, they convene with these scenes exceptionally well. A jack of all trades and master of all of them, William Nicholson was an independent talent. He stood apart from the groups, movements, and even Wyndham Lewis’ English Vorticism. His great skill was graphic and social, whether ordinary people or extraordinary talents of his era, and of course, his portrait of Queen Victoria – Aubrey Beardsley’s favourite!

William Nicholson, 22 November 2025 – 10 May 2026, Pallant House Gallery, Chichester

Visit Here