Victoria Miro presents Alice Neel: There’s Still Another I See, an exhibition that focuses for the first time on pairings of Neel’s paintings of the same sitter.

Among the foremost painters of the twentieth century, Alice Neel’s reputation has only ascended further during recent years, with landmark exhibitions such as the acclaimed 2021–2022 touring survey Alice Neel: People Come First, organised by The Metropolitan Museum of Art in association with the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao and The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Throughout her life, Neel (1900–1984) developed a unique talent for identifying particular gestures and mannerisms that reveal the singular identities of her sitters. Yet, she was also acutely aware of changes within an individual in spirit and in flesh, and how these changes might reveal themselves over minutes, days or decades. The above quote, in which Neel describes her experience of painting the poet Frank O’Hara, gives a sense of what compelled her to look at and paint people more than once, and by extension to know as much as possible about the people and the world around her.

This exhibition, the first of its kind, focuses on pairings of paintings by Neel of the same sitter, sometimes completed only a year or two apart, sometimes decades apart. With works ranging in date from the 1930s to the 1980s, it charts physical transformations over time, changes of mood, temperature or temperament – in sitter and artist – along with developments in Neel’s art, which grew ever more penetrating and succinct.

The domestic habitat of her family provides a focus. Neel completed just four paintings of her mother, Alice Concross Hartley Neel (1868–1954), two of which will be on view: My Mother, 1930; and My Mother, 1952. Painted 22 years apart, they reveal a strong empathy for the changes in body and mind that accompany old age. Yet, just as striking is an unusual dynamic – that of the artist looking and, just as powerfully, being looked at by her subject. Neel said that it was through the expression of her mother’s face that she judged her own actions; as she explained to art critic Judith Higgins ‘My psychiatrist told me I got interested in painting portraits because I liked to watch my mother’s face… It had dominion over me. Since she was so unpredictable, he thought I watched her face to see whether she approved of things or not.’ **

Paintings of Neel’s elder son, Richard, show him as a teenager and as a man in his early 40s. Both are profile views, and near mirror images across time. In the earlier work, completed in 1952, Richard is depicted in a garden where, having just turned thirteen, he appears somewhat sullen, the vines in the background – a classical motif of burgeoning sexuality used by Neel since the 1930s – if not an explicit pronouncement of her son’s arrival at this milestone, then an indicator of prevailing mood. In the later work, completed in 1980, Richard is again seated outside, tucked into the corner of a garden bench, casually dressed in shorts; by this point in his life he had become a successful lawyer.

A thirty-year timespan separates paintings of Richard Neel’s father, José Negron. Neel first met Negron, a Puerto Rican nightclub singer and guitarist, in around 1934 and her 1936 painting of him reveals the intensity of Negron’s glamour and Neel’s ardour. They lived together, first in Greenwich Village then in Spanish Harlem, until 1939 when Negron abandoned Neel and their three-month-old son. Neel didn’t see Negron again until 1966 when she visited San Miguel, Mexico, with Richard. While Negron wears a white shirt as he did three decades earlier, very little of the former romantic lead is evident in the later work, in which the man we see before us is no longer a nightclub singer; Negron would go on to become an Episcopal priest.

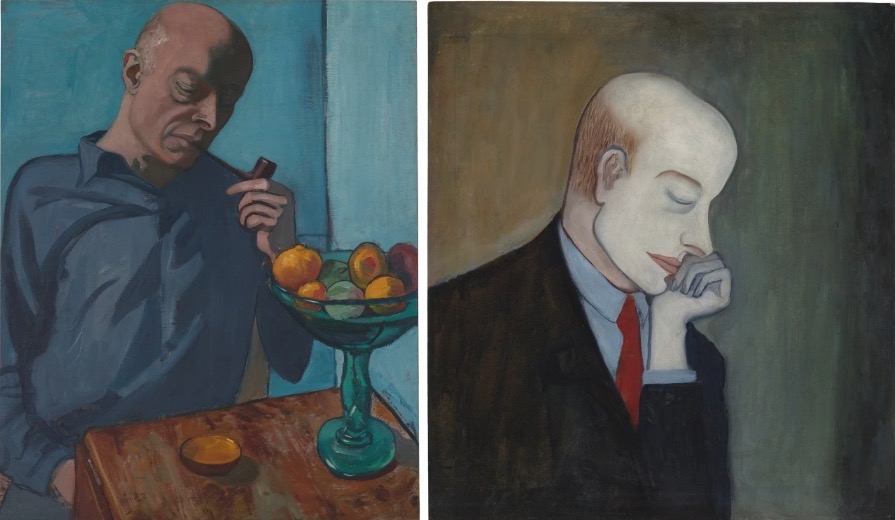

Neel first met John Rothschild (1900–1975), a Harvard-educated businessman, at the Washington Square Park annual outdoor exhibition in 1932, where she was exhibiting. Neel later described him as a ‘great companion’, though she went on to add, ‘the only compatible life we have together is across the dinner table’, and they remained loyal friends until his death in 1975 (in fact from 1970 until his death Rothschild lived in Neel’s spare room). A dreamlike atmosphere pervades Neel’s 1933 painting of him, while John with Bowl of Fruit, painted in 1949, has an air of calm as well as contemplation that seems to speak to the ease of friendship.

Ellie Poindexter was a New York gallerist who Neel painted twice in quick succession. Keen to cultivate a professional relationship, Neel made a flattering first depiction in which Poindexter wears a lilac dress with a rose corsage. The second, painted from memory after a disappointing encounter, demonstrates in no small measure Neel’s ability to convey her psychological impressions of her subject. Colour and personal detail were instrumental signifiers for Neel, and here, Poindexter becomes as she existed in Neel’s mind – a rather brittle figure with breasts protruding pneumatically within her yellow dress, a fox fur slung around her neck. Poindexter never got to see Neel’s more rancorous version.

Neel said, ‘If I hadn’t been an artist, I could have been a psychiatrist.’ In presenting Neel’s paintings of the same subject, this exhibition invites consideration of her desire and motivation to look and paint again, in addition to the constancy of her vision and the unwavering visual and emotional intelligence she applied to others.

| Duration | 11 October 2022 - 12 November 2022 |

| Times | Tuesday–Saturday: 10am–6pm. |

| Cost | Free |

| Venue | Victoria Miro London |

| Address | 16 Wharf Road, London, N1 7RW |

| Contact | 4402073368109 / info@victoria-miro.com / www.victoria-miro.com |