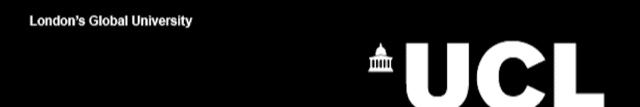

Andy Friend’s Comrades in Art is a remarkable excavation of a decade when British art and politics collided with an urgency rarely seen before. This is neither a conventional group biography nor a dry academic chronicle.

The author has uncovered a tangled network of Artists (AIA), a collective formed in the ominous period of the 1930s, when unemployment, fascism, and the gathering storm of war compelled artists to take a stand politically, sound familiar?

The book begins in the 1930s, when Hitler’s rise and mass unemployment at home reshaped the cultural landscape. Against this backdrop, the AIA emerged as a loose alliance of painters, sculptors, designers and writers who believed art had a public duty. Their response was not just aesthetic; it was activism. Murals, posters, exhibitions and demonstrations became their vocabulary. Friend shows how this movement, dismissed for decades as marginal, was in fact central to shaping post-war attitudes toward art and politics in Britain.

Among the cast are names familiar from the canon, Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore, Paul Nash, David Bomberg—alongside lesser-known but no less pivotal figures such as Cliff Rowe, Pearl Binder and Misha Black.

Andy Friend treats both groups with equal seriousness, showing how the famous and the forgotten shared the same space, often in the same cramped meeting rooms, debating how best to resist fascism through culture.

The AIA was born of optimism but riven with contradictions. Its name alone was initially a compromise, too close to the Comintern. softened with the addition of “Association.” Its members flirted with revolutionary rhetoric, yet many were pragmatists keen to avoid alienating wider support. Friend illustrates this tension vividly, from Peggy Angus painting a cement works on Bloomsbury’s doorstep to Rowe’s Moscow mural “The Struggle Between the Unemployed and the Police Forces,” painted from newspaper clippings of Hyde Park protests in which mounted police bloodied unemployed marchers.

The book also opens out beyond Britain, reminding us that these debates were international. The New York commission fiasco—where Rockefeller and Morgan recoiled at murals casting them as gangsters—underscores how artists worldwide were challenging the connection of money and culture. The same battle lines were drawn in London, Berlin, Moscow, and New York, giving Comrades in Art a broader resonance.

Friend’s research animates the book with its narrative drive. He writes with an eye for drama—the image of Angus’s easel pitched against the Woolfs’ beloved Downs lingers long after the page is turned. There are flashes of humour too, as when MI5 trailed members for their flirtations with Soviet culture, and moments of poignancy, with artists caught between careers, convictions and survival.

At a time when we are again seeing the rise of the far right in Britain, Friend’s book feels urgent. Comrades in Art restores to view a generation that believed art could intervene in the world, not merely decorate it. For anyone interested in the politics of culture, it is essential reading.