For thirty years, Darren Almond has explored the nature of time through several distinct yet mutually reinforcing streams of work. Now is a good time to take his measure, as not only does he have a solo show at White Cube Mason’s Yard but you can also see his art in the recently-opened Bond Street station on the Elizabeth Line. Life Line (to 4 May) is a good chance to consider his fractured numbers, seasonal tree paintings and moonlit photographs.

How should you be pronounced?

Most people say Ar-mond. A few say Al-mond. I say ‘All-mond’ – that’s how it’s pronounced in the north-west, as in the nut.

What’s the source of your fractured numbers?

The calligraphy of the paintings comes directly from digital clocks. When these kind of clocks started to appear on railway platforms in the seventies, it marked the transition to the digital age: people thought ‘Ah, here comes the future!’ I was doing a computer studies course and the tutor said if you look at a clock, the analogue is continuous, the digital is in steps. It’s a mechanical divide in time that pretends to more accurate, but that’s a kind of an illusion. And you lose something when everything is binary, either a yes or a no. You lose the continuity, and the connection to the sun’s cycle…

What started your use of digital clocks?

The first work was a satellite broadcast – from my studio, into a disused space (‘A Real Time Piece’, 1996). I had come across an early CCTV in a shop, and thought – ‘Orwell is back!’ He was something of a spiritual guide for me, for how he approached social commentary through razor sharp writing, nothing airy-fairy. The more so as I come from Wigan – mine is the road from Wigan Pier! So I set up a relay back to the view of my studio as a real-time event, a performance piece. It needed a marker, so the clock was introduced – with a microphone inside, so it is very loud when each minute clicks past. After the event, it had gone, so I thought: ‘what if I photograph the clock?’ So I sat for 24 hours taking an analogue photograph every minute for those 1,440 minutes. That led to almost euphoric experiences of sunrise and sunset, when the back wall of the studio seemed to glow because of my concentrated meditation on the space. Then I started to use clocks sculpturally – as in ‘Tide’, the whole wall of 600 synced clocks I showed at Parasol Unit in 2008.

Darren Almond: detail from ‘Inari Chimera I-VI’, 2024 – Gold and acrylic on linen, 6 canvases each 182 x 128 cm. Photo: Paul Carey-Kent

Darren Almond: detail from ‘Inari Chimera I-VI’, 2024 – Gold and acrylic on linen, 6 canvases each 182 x 128 cm. Photo: Paul Carey-Kent

And the fragmentation?

I was speaking to a German curator who complained about the trains not being on time, as they were in Switzerland. I said – ‘You should come to England!’ But that gave me the idea of the station clock being broken. So I started to collect the same clocks, but pulled all the blades out, jumbled them up and reassembled them so they all kept time in perfect harmony and had this metronomic unified sound – but the display was this gobbledygook of abstraction. Then I started to distil that look down into paintings, initially in black and white. Several steps on, the language has developed….

Darren Almond: ‘Inari Chimera I-VI’, 2024 – Gold and acrylic on linen, 6 canvases each 182 x 128 cm. Photo: Paul Carey-Kent

Darren Almond: ‘Inari Chimera I-VI’, 2024 – Gold and acrylic on linen, 6 canvases each 182 x 128 cm. Photo: Paul Carey-Kent

You’ve spent considerable time in Japan. I guess the title ‘Inari Chimera’ for the six paintings arranged together relates to that?

Yes. The colours are autumnal, but also derive from the Fushimi Inari Taisha shrine in Kyoto, where the landscape can be seen through a sequence of vermillion Torri gates. And there are often fires in the temples, like the one I filmed for ‘Sometimes Still’ (2010), as part of a six screen film engaging with the Buddhist process of Kaihogyo, the feat of physical and mental endurance by which monks attempt to discover ultimate truth and fulfilment. That experience informs the whole show. The monks run some 25,000 miles – the equivalent of the equatorial distance round the world – over a seven year period. The full cycle concludes with runs of 70 miles a day for 100 days, then staying awake for a week chanting into a burning fire, by which point they’re so dehydrated they’re perspiring their own blood. The monks take a very calculated step towards death, then turn round and come back – and are deemed to be living Buddhas. They’re very cagey about westerners – it took me four years to arrange to run one path with a monk. They wanted to know why I was interested, but I couldn’t really say, other than that a childhood experience of running terrified through a forest had stayed with me. The chimera is as in the ungraspable. Zero is the biggest yet least visible integer here – present yet not present, the infinite’s twin in a sense.

That’s a lot to unpack…

But also not. There’s an emptiness and calm. Or you can just take it as an abstract language. I find myself reading it, playing it, dancing around it. The colours and placements are intuitive, and there is no significance to the numbers, only to their placements as choreography.

Darren Almond,’Life Line’, White Cube Mason’s Yard, London 20 March–4 May 2024 © Darren Almond. Photo © White Cube (Eva Herzog)

Darren Almond,’Life Line’, White Cube Mason’s Yard, London 20 March–4 May 2024 © Darren Almond. Photo © White Cube (Eva Herzog)

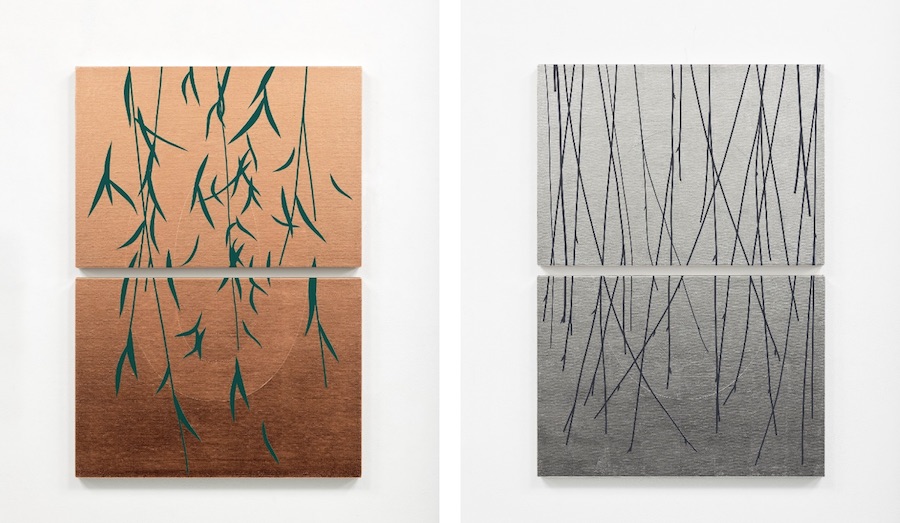

The ground floor puts the viewer in the middle of 38 paintings created with precious metal leaf – gold, palladium and copper – depicting the willow tree at various stages of their annual cycle…

Yes, it starts at the window which is only one to let natural light into the gallery spaces at Mason’s Yard. Autumn copper turns to winter palladium and spring-summer gold…The willow is among the first trees to grow its leaves and also hangs on to them the longest. Do you know, by the way, why the weeping willow is so called?

Is it the mournful downward sweep of the branches?

That’s what I’d thought, but no! When it rains in winter, the water clings to the hanging braches and the capillary action causes it to flow down to the tips and weep.

Darren Almond: ‘Senryū (autumn)’ – Copper and acrylic on linen – and ‘Senryū (late winter)’ – Palladium and acrylic on linen: both 2024, 90 x 63 cm. Photos: Peter Mallet. Courtesy White Cube.

Is it expensive to work with metal leaf?

It is. You can’t get platinum any more due to Russian war. Palladium, next to it in the periodic table, is the most expensive. That’s a double thickness of 23.5 Carat gold: that’s quite some weight of gold per painting. That won’t tarnish, whereas copper will, so it is sealed. The metals do this wonderful thing of finding light. You see how that works in ancient Japanese lacquer furniture with flecks of gold in it.

How have those faint zeros been made?

They are debossed, raised – there / not there – you complete the zero. The zero reinforces that the paintings are about time. Zero is the youngest numeral: it didn’t come about until Buddhism started thinking about nothing. In Europe in pre-Renaissance times the concept of nothingness was absent. Its arrival coincided with perspective – with zero as vanishing point.

The show concludes with one of your ongoing series of night photographs revealing the details of the darkened landscape that the human eye cannot see. How are they made?

Through a single, analogue exposure, by the light of the full moon but not depicting the moon directly. The length of exposure varies depending on weather conditions – in a super-clear Californian night sky, 12 minutes with 160 ASA film; in Japan, when mists came in, 40 minutes might be needed. Cloud is not a problem, it just takes longer. Years of practice tell me when to stop. I prefer to shoot through the winter, as it is darker for longer. I shoot more than once in a night, increasing the chance of finding something good when I get back to the darkroom. I like that uncertainty, it’s unlike the digital experience – you’re more emotionally engaged with your subject matter at point of exposure. With digital you can review as you go, and decide to change this or that – and then your dumbass intelligence kicks in. I’m a bit stupid and would otherwise make a mistake by correcting myself!

‘Fullmoon @Wall (In Memoriam)’, 2024, shows the iconic Sycamore Gap tree at Hadrian’s Wall, vandalistically cut down in 2023. You see that as concluding the show?

It seemed an appropriate end, though the final addition was Jules Laforgue’s poem ‘Dialogue before Moonrise’. I came upon that at the last minute and thought ‘this is insane!’

Top Photo: Darren Almond Portrait – Courtesy White Cube

Darren Almond: ‘Life Line’ continues at White Cube, Mason’s Yard to 4 May